|

|

|

|

November

30, 2006: Lulu Status Report November

30, 2006: Lulu Status Report

I

finally got a book configured and available for sale on Lulu

this morning. As a publisher, I was surprised at how easy it was.

However, if I were not a publisher, it would have taken a great

deal more close attention and experimentation. The truth is that

publishing isn't trivial, and Lulu has done a superfine job presenting

publishing's complexity to the inexperienced in the form of good

wizards, sane organization, and decent doc. I

finally got a book configured and available for sale on Lulu

this morning. As a publisher, I was surprised at how easy it was.

However, if I were not a publisher, it would have taken a great

deal more close attention and experimentation. The truth is that

publishing isn't trivial, and Lulu has done a superfine job presenting

publishing's complexity to the inexperienced in the form of good

wizards, sane organization, and decent doc.

The book is one that I originally scanned, OCRed, and laid out

a few years ago, and could never quite decide how to release. It's

The New Reformation,

a contemporary history of the origins of the European Old Catholic

movement, by James Bass Mullinger, a Cambridge historian best known

for his massive three-volume history of Cambridge University that

spanned most of his productive life. The book was written and published

in 1875, and reads more like a journalistic account than a history.

Most accounts of the Old Catholics and their struggles with Rome

have been written by their antagonists, primarily the Roman Catholics,

but in later years by conservative Anglicans as well, who considered

the Old Catholics another body of competitors for non-Papal Catholic

adherence. Mullinger (writing under the pseudonym Theodorus) was

plainly sympathetic, and there is a level of detail supporting the

Old Catholic case that the Old Catholics' detractors obviously don't

care to mention.

Now, this is pretty narrow material, and I suspect that few if

any of ContraPositive's regular readers are within its primary audience.

But that's the magic of a system like Lulu: I can make the book

available for sale, and if only 50 people buy it, I won't lose my

investment in the rest of a 1000-book press run. If bookstores won't

shelve it (and trust me, they won't) I don't have to worry about

warehousing, inventory logistics, and the inevitable returns accounting.

In fact, Lulu does all the legwork of order taking, payment processing,

and order fulfillment. They take their cut, but my spreadsheeting

tells me that I'll make more (though not radically more) per copy

selling through Lulu than I would as a publishing house using conventional

retail channels. Of course, the book is not one that would likely

ever justify a conventional print run, so Lulu (and similar systems

like IUniverse) have basically

made its publication possible.

Some notable points about Lulu:

- Lulu has a nice collection of stock cover art, and you can generate

a cover automatically by entering the cover text (for the front

cover, at least) and choosing an art design from the stock catalog.

I chose a stock design for some test copies of a new layout I'm

creating for a new book series and had them shipped back to me,

and was quite impressed by the quality of the color cover. (The

New Reformation uses a b/w cover.)

- Creating a custom cover with your own art and layout is a little

trickier, but Lulu does help. After you upload the body of the

book as a PDF file, Lulu will calculate the dimensions of a wraparound

cover for you. This is very useful, because the dimensions of

the cover are extremely touchy if you want your spine text

to be centered on the book's spine.

- Lulu does some validations on the PDF files that you upload,

to ensure that the files conform to its requirements and to one

another. The last page must be blank, for example, and the number

of pages must be evenly disivible by four. Also, if you design

a cover yourself and upload it as a separate PDF file, Lulu will

calculate whether the size of the cover is correct for the size

of the body of the book as present in the other PDF. I came to

appreciate this when I uploaded an old cover PDF by mistake that

wasn't of a size to match the final book body PDF. Lulu called

me on it. All in all, quite impressive.

I haven't bought the distribution package that includes an ISBN

and distribution through other retailers, in part because the book

won't benefit from such distribution, at least immediately. I'm

hoping that they will allow me to use the book of ISBNs that I already

own, but if that falls through, the option is available.

Lulu also distributes downloadable ebooks, and my next Lulu project

will be a longish short story. I'm interested in seeing if anybody

will actually buy "a story for a dollar" as pundits in

the SF/fantasy arena have been predicting for years. ($1 is the

minimum price for downloadable files.) The trick there has nothing

to do with Lulu: I have to learn how to create a decent-looking

ebook for Microsoft Reader. The little Word plug-in that Microsoft

distributes for free doesn't even respect line centering, and I'd

like to do a little better than that. (CSS is the high road, but

I am so rusty at CSS...)

After that, I have a whole list of projects already underway, including

another Old Catholic reprint from the 19th Century. Right now, I have

to slide over to the Old Catholic gang and let them know that the

book is ready. I've been talking about it since 2002, and I'm sure

most of them by now think that I've given up. Better late than never,

heh.

|

November

29, 2006: The Fattest Computer Book in History? November

29, 2006: The Fattest Computer Book in History?

Carol and I were down at the

ARC thrift shop earlier today, looking for a couple of pieces

of Corelle Ware. Not a whole set; just a couple of plates and/or

bowls in which to microwave leftovers. Nothing there but a couple

of Corelle saucers, and saucers (by which I mean little plates with

cup-sized dents in them) are about as useless as tableware gets.

No matter. We were in the neighborhood. And they had a book rack.

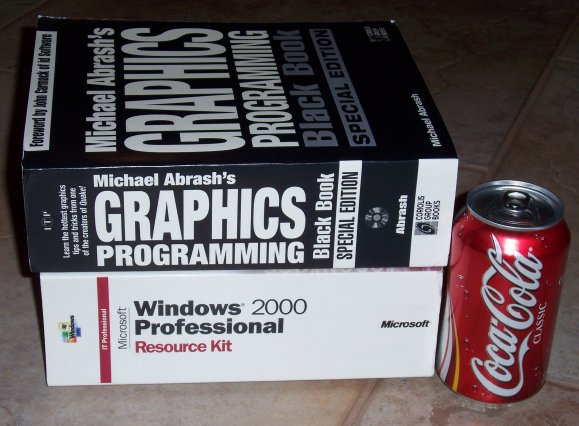

I scanned it quickly, and spotted a copy of what may well be the

fattest computer book ever published: Windows

2000 Professional Resource Kit, written in-house at Microsoft

and published in 2000, for $70. The book is the same width and height

as most computer books, but it's 1,770 pages long, and is 3 1/8"

thick. Even the titanic Michael Abrash's Graphics Programming

Black Book, which Coriolis published in 1997, only went 1, 342

pages and was a mere 2 5/8" thick. The only other thing in

my library that staggers into the same ballpark is the 15th anniversary

edition of Upgrading and Repairing PCs, which hit 1,575 pages

but is still a quarter inch thinner than Microsoft's Great White

Whale.

It's not a bad book, though the publisher in me feels that its

page count was mostly a stunt, and it would have worked better as

two smaller volumes. Books with spines the size of eastern rural

counties fall apart under even moderate use, as we found to our

dismay with the Abrash tome. The copy of the Windows monster that

I found looked almost unused—and I got it for $2.99. Is that

a deal or what? (It certainly is if, like me, Windows 2000 is the

platform on which you do all of your paying work.) If you have a

fatter computer book, do send me measurements and a citation, but

I think this one gets the prize. I can see Steve Ballmer storming

into the Microsoft Press offices one day in 1999, on the eve of

the release of Windows 2000, and yelling "I WANT US TO HAVE

THE FATTEST COMPUTER BOOK EVER PUBLISHED! DO IT RIGHT NOW OR I'LL

START THROWING CHAIRS!"

Hey, have you got a better explanation?

|

November

28, 2006: Massive Spam Parallelism November

28, 2006: Massive Spam Parallelism

One reason we will not be rid of spam anytime soon is that spam

is very well suited to massively parallel mechanisms. The recent

uptick in my spam (and everybody else's, I suspect) is due to the

fact that more bots are being knit into botnets, and they're better

bots. Even Port 25 blocking, which I thought was foolproof, will

not deter them long-term. Here's why:

- Bots can easily find saved logins and passwords for the local

ISP's SMTP server. Who doesn't let the client remember passwords?

Even if port 25 is blocked and the ISP's outgoing mail server

is the only one easily accessible, the bots can use it.

- Even where ISPs put explicit limits on the number of outbound

email messages from any single customer system, given enough bots,

huge numbers of messages can still be sent. You just need to divide

the work out so that no single bot delivers more than thirty to

fifty messages per day. If there are 10,000 bots in your botnet,

you can still make a lot of money.

- Until spam threatens the revenue stream of a Big Entity, nothing

much will be done about it. P2P is a shadow of what it once was

because Big Media mounted what at times looks like a terror campaign.

Even though much of what spam pushes is fraudulent or even illegal,

the spammers seem to be steering clear of most IP crimes. My best

hope is that the SEC will get serious about spam-based penny stock

fraud, but as the SEC has never had much interest in penny stocks,

the fraud will likely go on.

- Botnets now work command-and-control through IRC channels, but

if the IRC ports are blocked at the ISP level, it's almost trivial

to use HTTP tunnelling or some other protocol that uses essential

ports. As long as there's money in spam, the spammers will figure

out ways to keep their botnets alive.

In the meantime, I get over 100 penny stock pump-and-dump pitches

per day now, five times what I got a couple of months ago. Mortgage

refi spam is almost gone; amazing what changing interest rates did

for my inbox. Porn spam, too, has almost vanished, though I got

a spate of almost incoherent messages last week offering me pictures

of a woman working under the name "Texas Elegance" who

appears to be a 50-year-old porn star.

Eliminating botnets may be the computational problem of the

first half of the 21st century. I'm not kidding. Figure that out,

and you will rule the world.

|

November

27, 2006: More Cute Dog Pictures November

27, 2006: More Cute Dog Pictures

Earlier today, a reader who will remain anonymous demanded, "Less

religion and more cute dog pictures!" I guess not everybody

has the same priorities. So here's a nice picture of QBit and Deano

taken oh, half an hour ago. God's patient; He can wait until next

week.

|

November

26, 2006: Dogs Watching TV November

26, 2006: Dogs Watching TV

Last night Carol and I reviewed the Mini-DV camcorder tape I had

just filled, and we saw something we had never seen before: Dogs

raptly watching TV. Much of the tape was footage of the local bichon

breeder's two latest litters of puppies, which Carol and I spent

some time with earlier this year to help get them used to people

and being handled. When footage of the puppies was on the big-screen

TV, QBit watched intently from his perch on the back of the couch.

Deano, our bichon guest for the past week, wasn't content to watch

from a distance. He went right up to the TV and watched while standing

on his back feet. (That's Deano in the photo above.)

Although both QBit and Deano watched when footage of QBit (or some

of Jimi's other adult bichons) was on screen, their attention sharpened

considerably when the focus was the five week old or eight week

old puppies. This was interesting, because QBit doesn't much like

puppies, and always tried to hide from them whenever we had him

over there for a haircut this spring. Deano was the same way: He

kept his distance from the puppies, and even occasionally growled

at them when they approached him, wanting to play. Yet when the

puppies were on TV, neither could stop watching.

I'm not sure what this means, but it was a fascinating thing to observe.

I always thought that dogs ignored the TV because they didn't know

what it was, and the light patterns didn't mean anything to them,

but in that I was dead wrong. Dogs will watch TV when the subject

is something of compelling interest to them. Why QBit and Deano were

intent on watching puppies when neither of them enjoyed being with

puppies is even more interesting. Male dogs may have evolved to watch

over their young without particularly enjoying their company. It would

be interesting to park a female bichon in front of the TV to see what

her reaction would be. We may borrow one of Jimi's females at some

point to perform the experiment. I'll report here when we do.

|

November

25, 2006: Another Year, Another Dollar November

25, 2006: Another Year, Another Dollar

The

US mint has designed yet

another damned $1 coin, to be turned loose next February. It's

going to be the same size and color of the current Sacajawea dollar,

and have a rotating obverse to honor all of our deceased Presidents,

with one President featured every two years. The design is not stellar,

in my view, and I don't expect anybody to use them heavily, though

I will probably frame the Millard Fillmore dollar when it appears

in 2010. Although he got onto a pointless 13c stamp during the Depression,

poor President Fillmore has never gotten anywhere near a coin, which

is unfair, even for a man whom Mark Twain said "proved that

no one can grow up to be President." He brought books in quantity

to the White House for basically the first time, and I honor him

for that. (He is said to have installed the first bathtub as well,

but that's a legend circulated by H. L. Mencken.) He was the last

President to be neither a Democrat nor a Republican, and late in

life turned down an honorary degree from Cambridge University because

he felt he lacked the education to warrant it. Basically, a contrarian,

and a fairly humble one too. The

US mint has designed yet

another damned $1 coin, to be turned loose next February. It's

going to be the same size and color of the current Sacajawea dollar,

and have a rotating obverse to honor all of our deceased Presidents,

with one President featured every two years. The design is not stellar,

in my view, and I don't expect anybody to use them heavily, though

I will probably frame the Millard Fillmore dollar when it appears

in 2010. Although he got onto a pointless 13c stamp during the Depression,

poor President Fillmore has never gotten anywhere near a coin, which

is unfair, even for a man whom Mark Twain said "proved that

no one can grow up to be President." He brought books in quantity

to the White House for basically the first time, and I honor him

for that. (He is said to have installed the first bathtub as well,

but that's a legend circulated by H. L. Mencken.) He was the last

President to be neither a Democrat nor a Republican, and late in

life turned down an honorary degree from Cambridge University because

he felt he lacked the education to warrant it. Basically, a contrarian,

and a fairly humble one too.

Anyway. I have yet to hear any sense spoken about why our last

two dollar coins have not clicked with the public: They look too

much like quarters, and there are both practical and mythic problems

with that. The public perception of the "incredible shrinking

dollar" is not helped by a coin that looks no larger than a

quarter, and I think it's discourteous to blind folk (who like coins

because they can be differentiated by feel with a little practice)

to add that kind of confusion to their pockets.

Government arguments that a larger dollar coin would cost too much

in metal are specious; unless a coin cost more than a dollar to

make there's really no problem, and a coin can last in circulation

for fifty or sixty years. I got a 1940 Jefferson nickel in change

last week, and while it had been around the block a few times and

looked the part, it still helped pay for my chicken sandwich. A

dollar coin that will last for sixty years doesn't have to cost

a nickel to mint. Just consider how many dollar bills must be printed

and shredded in that same time period.

My suggestion: Officially retire the half dollar coin (no great

loss; I've not seen one in change in 25 years) and make a dollar

coin that is 15% larger than the traditional half-dollar, and a

little thicker. Keep the golden metal mix, or use something like

the UK pound coin, which is a handsome pale copper-nickel color

much like the US mint used on certain coins (like the wonderful

Flying

Eagle penny) in the 19th Century. On a recessed place on the

coin's reverse, put the denomination in Braille.

That done, leave the design unchanged...forever. The same image of

Abraham Lincoln has been on our penny for just under 100 years. That's

how I like my coins: Reliable and eternal—rather like a dollar

should be, but isn't.

|

November

23, 2006: The Purpose of Purgatory November

23, 2006: The Purpose of Purgatory

Just a quick postscript to yesterday's entry, after which I will

let the whole God thing rest for awhile.

A reader wrote last night to ask me if I believed in Purgatory.

Well, yeah—just not the Medieval concept of temporary divine

punishment that you could buy your way out of with prayers or money.

Simply because the concept was abused—and abused horribly—doesn't

mean that it has no merit.

If I have a personal theology of Purgatory, it cooks down to this:

Purgatory isn't about punishment, and especially pointless, Dante-esque

torture-style punishment. It's about Learning Better. It's about making

mistakes and paying for them in their natural consequences so that

we don't make those mistakes again. We enter Purgatory at birth, and

we do not leave it until we attain the ineffable state of the Beatific

Vision, having worked on our flaws across unknown realms where time,

space, thought, and feeling may not be precisely what they are here

on Earth. In the process, what we will ultimately learn is what it

means to have been created in the Image and Likeness of God; that

is, to be truly and completely human.

|

November

22, 2006: Mysteries, Absurdities, and Fideism November

22, 2006: Mysteries, Absurdities, and Fideism

I got a disturbing email the other day, from a guy who had stumbled

on my site while looking for information on space-charge

tubes, and then "read the whole thing." (Whew! That's

persistence!) After complimenting me on the techie/philosophical

stuff, he then wrote: "Put as simply as possible, the Christian

message is this: God hates me because of something I didn't do,

and if I don't say the magic words, 'Jesus Christ is my Lord and

Saviour,' God will torture me in Hell forever. How can you possibly

believe in crap like that?"

The short answer is that I don't. (I made this clear in my reply,

some of which I'm adapting for this entry.) The understanding of

Christianity that he cited isn't the only one; it's just the one

that gets the most airplay these days. It's also the one that brought

me within a quarter of an inch of throwing Christianity over the

side completely. (At some point I'll work up the courage to describe

a night I spent watching something called "Christian wrestling,"

which was as surreal as it was appalling, and almost made an atheist

of me.) Nonetheless, great huge swaths of the Christian world do

believe this, even though it's a pretty concise statement of the

Great Heresy, Manichaeism, which Augustine of Hippo injected into

Christian Tradition.

The Catholic interpretation of the Christian message is different,

but it still gnaws at me. In place of Calvinism's cruel God, Catholicism

and several other Christian traditions see a defeated God, who settles

for half a loaf and accepts that a certain number of persons will

just get lost in the darkness and never find their way home.

Belief as a mechanism seems inborn in some of us, and I'm certainly

in that camp. However, if I professed belief in either the Calvinist

(cruel) God or the Arminian

(defeated) God, I would be guilty of a philosophical position called

fideism—believing

in something even though you know that it's absurd.

I need to point out here that there are mysteries, and there are

absurdities. Drawing an analogy to mathematics, it's the difference

between fast

Fourier transforms and dividing by zero. Fast Fourier transforms

are extremely difficult to understand, and when I'm being honest

with myself I admit that I'll go to my grave without understanding

them. Dividing by zero, on the other hand, is simply absurd. There's

nothing there to understand.

So things like the doctrine of the Trinity don't bother me at all.

Humility requires me to admit that I can't understand it, at least

in this life and at this state of my intellectual development. That

doesn't mean the concept is absurd. In fact, it rings with a kind

of truth that keeps me going, even in the face of toxic religion.

The Trinity is a mystery, as is the dual nature of Christ as true

God and true man. Neither is easily understood, but neither is a

contradiction in terms.

Now, when you come to the notions of a cruel God or a defeated

God, the contradictions emerge. An all-good God cannot be cruel,

and an all-powerful God cannot lose. To say I believed in either

would be self-deception, and this is why I profess belief in an

all-good and all-powerful God who will do whatever it takes

to gather everybody and everything back into Divine wholeness. Real

God, no compromises, no contradictions, no absurdities.

This doesn't mean that we won't be slogging through a certain amount

of Hell in the meantime. Anyone who has watched a loved one die

horribly (as I watched my parents die) will understand this. Suffering

itself is a kind of mystery, and one way to understand the Incarnation

is to realize that God has told us that He is suffering right down

here with us, and that suffering has meaning, if not meaning that

we can necessarily understand in the here and now. The notion of

a suffering God bothers a lot of people, but it makes perfect sense

to me: God is everything we are and infinitely more, and if so much

of human life is suffering, God Himself cannot escape. The life

of Christ is God telling us to hang in there, that we are not alone,

and that (deny it as some of us try) in the end all things will

be brought back to wholeness.

The real Christian message is implicit in the life of Christ. Hell

shows up in a couple of places in the Gospels, but from a height they

fade into the noise. What stands out are the miracles of Jesus, which

could have been advanced parlor magic like turning sticks into snakes

but are not: They are all movements from suffering and brokenness

back to wholeness. Feeding the hungry, healing the sick and the maimed,

bringing people back from the dead, yikes! That's where it's all going.

So in response to the Augustinian understanding of the Christian message

I'll posit this: God created us radically free, and the cost of freedom

is suffering, but the upside—participation in the Divine Nature—is

huge, if not easy to understand at this point in our journey. God

doesn't lose, and ultimately we'll all get there, and in the meantime,

the message of Christ stands out in bright lights: Heal one another,

as I have healed you.

|

November

21, 2006: My New Custom Table November

21, 2006: My New Custom Table

I don't think I ever posted a photo of my new work table, on which

my main system, printer, and new scanner live. (Yes, the scanner

stand is a scrap lumber lashup, and I'm designing a better one.)

When we moved into this house, I bought an oak table that was about

the right width and depth, but which was at least 4" too high.

The height of the table coupled with the size of my 21.4" Samsung

LCD monitor (operating in portrait mode, to boot) gave me serious

neck problems that I'm still dealing with. So I hunted around, and

in remarkably little time ran across a near-perfect table in knotty

alder at a local unfinished furniture place.

It was still too high, but they have a full wood shop in the back

room, and for another $100 I had them cut the trestle base portion

down so that the table surface is precisely 26 1/2" above the

floor. I had them stain it to harmonize with the rest of the wood

in my office (of which there is much) and then finish it with a matte

urethane that filled the cracks in the knots right up to the surface.

It's strong, precisely the right size, and gorgeous. I paid a little

more for it than your average computer desk (about $750 total) but

given how much time I spend sitting in front of this damned box (and

how much of my living I make doing that sitting) I think it was worth

every nickel.

|

November

20, 2006: Reincarnating Mr. Byte November

20, 2006: Reincarnating Mr. Byte

As if we didn't have enough to do around here, Carol and I are

temporarily taking care of a friend's bichon. Deano is a show dog,

and still has all of his um, equipment. This makes him get a little

nuts when Jimi's females go into heat, which they all do at the

same time. So we're taking Deano until the heat's off back home.

Deano knows Carol, since she was doing a bit of appenticing on bichon

grooming under Jimi earlier this year. So although he's still a

little skittish, he's getting used to being away from home. Deano's

arrival has caused an interesting incidental phenomenon: Carol and

I have spontaneously begun calling QBit "Mr. Byte." It's

not deliberate, and happens most often when the two of them are

doing something we'd rather they not do.

Long-time readers of mine will remember that we had a bichon frise

named Mr. Byte from 1980 to 1995. I wrote about him a lot, and people

were asking me how he was doing long after he died of old age. QBit

looks superficially like Mr. Byte, but I don't think that's the

issue. Deano is younger and considerably smaller than QBit, who

at 16 pounds is on the high side of the envelope for the breed.

Mr. Byte was a good size too—and in 1982, we bought a second

puppy, the less famous Chewy. Chewy was always a little smaller

than Mr. Byte. So now we have a familiar pattern: Two bichons in

the house, one significantly larger than the other. Something in

the backs of our heads preverbally remembers the pattern, and when

it comes time to yell at QBit to get his nose out of the potted

plants, "Mr. Byte, stop that!" comes out of its own accord.

Interestingly, we haven't yet called Deano "Chewy." Maybe

that's the next step in this odd sliver of madness that comes of having

multiple bichons underfoot.

|

November

16, 2006: Here Comes Kathleen Elizabeth Roper! November

16, 2006: Here Comes Kathleen Elizabeth Roper!

Much

desired and very long awaited, but, well...beautiful! Nine

pounds, 14 ounces. Twenty-one inches long. I have it on good authority

that she has her father's hair and eye color. Much

desired and very long awaited, but, well...beautiful! Nine

pounds, 14 ounces. Twenty-one inches long. I have it on good authority

that she has her father's hair and eye color.

Better still, all involved with the project are healthy, though

Gretchen looks like she could use a few good solid nights' sleep.

I had to reflect earlier today: What did I ever want that I wanted

as badly as my good sister wanted to be a mother? Probably nothing.

I wanted to be an SF novelist (and it took about as long to get

there) but that's not in the same league. Wanting to marry Carol,

perhaps—though that only took seven years, not twenty-five.

Gretchen and Bill's persistence inspires awe, and when we got the

news this morning at ten to seven, it drew some tears as well.

It's pointless to say that the real work starts now. Most of that

falls to Gretchen and Bill, of course, but I'll have a chance to

pitch in. I have to learn Lego, and I still have to chase down a

few books that all kids need read to them, not once but many times.

I need to chase down a Polish nursery rhyme that my grandmother

used to recite while she rocked me in a little rocking chair. (It

begins, Ah, ah, kotka dwa...or something like that. I don't

know how to spell the words!) Beyond that, yikes! I don't know.

But there will be plenty of time to ponder the future. For the

moment, we're glad that the family is safe and healthy. It was only

briefly that I caught myself thinking, if only her grandparents

could be here to see her...

But how could I ever doubt that they are?

|

November

16, 2006: Prayers for our Imminent Brin November

16, 2006: Prayers for our Imminent Brin

I just heard that my sister Gretchen and her husband Bill had rocketed

off to Madison, Wisconsin to await the birth of their first child.

It was

an unconventional pregnancy, in that for medical reasons, they

had to have someone else carry the child to term, though the embryo

was fertilized in vitro and is completely theirs.

So. 25 shelf-feet of theology books in my library, and I finally

get to be a godfather! Figuring that the three of them (and the

carrier mother too) will need all the help they can get in the next

few days, I got up on the ladder and dug around on my high shelf

(missals and prayerbooks) looking for a prayer for safe delivery

of a child. Nada. I have prayers in books for some odd things ("Prayer

for a person one dislikes," and "Prayer for the solution

of a financial problem," among numerous others) but nothing

for safe delivery and good health for a new baby.

I guess I'll have to write my own.

All-powerful God, Creator of All Things and Ground of All

Being, grant a safe and healthy birth to this new life, and

give strength to the parents who conceived it and the woman

who bore it. Send your Spirit to give the child the breath of

life, so that she (or he) may be strong and joyous and rooted

in the Earth where we all dwell. Give us all the wisdom to know

when to advise and when to be silent, when to help and when

to simply stand back and let the child be human as we are human,

so that his (or her) humanity may be a beacon that we send into

the future, as we were sent by those who came before us. This

we ask, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the

Holy Spirit.

AMEN!

|

November

15, 2006: Good Pope Benny and Clerical Celibacy November

15, 2006: Good Pope Benny and Clerical Celibacy

The story was everywhere on Monday that today (Thursday) Pope

Benedict XVI will be holding a meeting with the Curia to discuss

the future of the thousand-year-old Roman Catholic tradition of

mandatory celibacy for priests and bishops. The immediate trigger

was another outburst from one of Rome's most embarrassing nutcases,

the defrocked Archbishop

Emmanuel Milingo, who (after a several years' dalliance with

the Moonies) has taken the celibacy issue on as his

Really Big Thing. (Just because I agree with him on this issue

doesn't mean he isn't a nutcase. You should read about his

exorcism masses, among other things.)

I will hand it to Archbishop Milingo: He hit Rome where it hurts.

Earlier this year, he consecrated four married men as bishops. At

least two of them have a long history with the Old Catholic Church,

and one of them (Peter Paul Brennan) I've spoken with. (Some information

on Bp. Brennan is here.

Scroll down a little; he's #3 on the page.)

The Vatican is in a bit of a spot here, because of the longstanding

Roman Catholic theology regarding apostolic

succession: The mental and spiritual state of the consecrator

does not affect the validity of the consecration. In other words,

even if Milingo is a few drills short of an index, if he follows

the accepted form for the ceremony of consecration, and if the bishops

he consecrates have the desire to become bishops, well, then they're

bishops. They may not be licit—legal in the eyes of the Vatican—but

they are nonetheless valid. And because a bishop is the highest

ordained office recognized in Catholic tradition, one representing

"the fullness of the priesthood," a bishop can consecrate

other bishops, and preside over an independent Catholic jurisdiction.

If this sort of thing happens too many times, you end up with splinter

churches all over the place.

Just as the late Pope John Paul II was an idealist, Good Pope Benny

is a pragmatist, and I've grown to like him. (Popes should not be

idealists. They have a Church to run.) He understands the weakness

of the celibacy tradition (it was enacted to keep children of priests

and bishops from claiming inheritance of Church property under the

emerging secular law of the Middle Ages) and its unpopularity with

the laity. He also knows that he's running out of priests. So while

it may not happen this year or next year, I think that the celibacy

requirement is going to go away fairly soon. (We will see the end

of the ban on women priests eventually, but it won't be within my

lifetime.) The Eastern Orthodox have never entirely banned married

priests, and Rome has quietly accepted a number of Anglican priests

with wives and families into its fold.

His big problem, of course, is how to pay for the upkeep of tens of

thousands of wives and kids, and the big question that Roman Catholics

have to ask themselves is this: Am I willing to cough up a lot

more to the Church to support clerical families? Protestants and Anglicans

do it as a matter of course. We'll see what the laity says when their

parishes ask for donations of thousands of dollars each year—not

merely the odd 20 that most people toss in the basket on Sundays.

|

November

13, 2006: Odd Lots November

13, 2006: Odd Lots

- Sun is releasing

Java under the same GPL V2 license that governs use and distribution

of the Linux kernel. Tim Bray, director of Web technologies at

Sun, fills

in some of the details here. It's interesting how the three

big players in this particular game (Sun, Adobe, and Microsoft)

all seem to be realizing how holding tight to a technology isn't

the way to get the world to embrace it.

- In response to my

half-serious Odd Lot about my Neanderthalic occipital bun,

I was pointed to a couple of Web documents on craniometry,

or the study of brain size and shape, and their implications.

On average (and taking general body size into account) Asian brain

cases are the largest, followed by European brain cases, followed

by African brain cases. Much nastiness has been tossed around

during discussion of such data, but what no one seems to mention

is that the Neanderthals had way bigger brains (and somewhat bigger

bodies) than any of us, and no one is quite sure why. (Here's

a

short, accessible introduction to this issue.) Craniometry

was not new to me, but what I hadn't heard is that in general,

the higher you go in latitude, the larger brain cases become.

Maybe it's a square-cube law thing: Bigger brains generate more

heat and would cook in equatorial climates, but not in Sweden.

I'm personally much more interested in how small a brain

case could be and yet still support intelligence like that of

modern humanity. Are Piper's Little

Fuzzies (14-inch-high humanoids) a physiological possibility?

I don't think we know enough about brain function yet to be sure.

- Jim Strickland sent me a

link to the European home of the Hubble Space Telescope, with

a nicely organized archive of spectacular photos. Dig in.

- I'm sympathetic to robots made out of all kinds of things, but

if I had to pick a system I'd want to fool with myself, I'd pick

Vex five throws out of three.

The Mythbusters guys did a

nice review on Robot Magazine, and I would characterize it

as a true Meccano/Erector Set descendent slanted toward robots.

Vex builders have a forum,

and I've seen a Vex robot beat all comers in a "critter crunch"

robot battle held at a Chicago SF con. I have too much invested

in vintage Meccano

and Exacto to throw

money into Vex, but it seems to be that the Vex remote control

systems and power trains might be adapted to Meccano girder hole

spacings.

|

November

12, 2006: Lee Anne and Middle Earth November

12, 2006: Lee Anne and Middle Earth

I began walking to The Lord of the Rings DVD again this

evening for the first time in awhile, as I probably will a couple

of times a year for the rest of my life. And when the first view

of Bilbo Baggins' stately hobbit hole Bag End appeared, I snorted

with abrupt recognition: I now have a house dug into the side of

a hill as well. Its interior even shares some stylistic touches

with Bag End, and lord knows there are lots of books scattered around

on oak shelves, beams against a vaulted ceiling, and always some

aged cheese, good wine, and rough bread within easy reach. I envision

myself curled up in a comfy chair with a good book, and I wonder

if I'm becoming a bit of a hobbit myself.

There's

some fair irony in that, especially considering my initial reaction

to Tolkien's expansive fantasy, which I began under some protest

at age 14. I read it at the behest of the little girl three houses

down the street, for whom I began to have strong feelings at that

time. (The photo at left of her at 13 is, alas, the only one I have

of her.) She'd been there since my earliest memory, and we'd always

played together, co-inventing imaginal worlds without any conception

of how good we both were at it. By the time we were 11 we both had

typewriters (didn't everybody?) and we wrote one another outlandish

stories. Hers leaned toward elves and dragons; mine toward starships

and aliens. No matter; we had a fine time together. There's

some fair irony in that, especially considering my initial reaction

to Tolkien's expansive fantasy, which I began under some protest

at age 14. I read it at the behest of the little girl three houses

down the street, for whom I began to have strong feelings at that

time. (The photo at left of her at 13 is, alas, the only one I have

of her.) She'd been there since my earliest memory, and we'd always

played together, co-inventing imaginal worlds without any conception

of how good we both were at it. By the time we were 11 we both had

typewriters (didn't everybody?) and we wrote one another outlandish

stories. Hers leaned toward elves and dragons; mine toward starships

and aliens. No matter; we had a fine time together.

I remember how she handed me The Fellowship of the Ring

when I was mostly through my freshman year in high school. It was

an elf thing, sigh, but she would brook no argument, and I was becoming

aware of a desire to please her that wasn't quite like the one I'd

felt in years past. So I sat down that night and the book just drew

me in, as it usually does to anyone with any imagination at all.

I remember grumbling about "all this magic stuff" but

damn, it was catching. My two best friends at school caught

it from me, and we read it and argued about it for the rest of our

time at Lane Tech.

Lee Anne was damned good at her storytelling, and she embarrassed

me a little by working my aliens-and-starships turf with a great

deal more aplomb than I could move in elves-and-dragons land. She

created aliens that looked a lot like elves but had starships, and

we played with an SF collaboration called The Timenor, which

was about her elfin telepathic aliens, their wicked cool starships,

and a battle with Cosmic Evil. Magic and telepathy were a natural

for her. On the other hand, in spite of all her encouragements,

I had a bitch of a time with the idea of magic or anything else

smacking of the supernatural. Reading about it was one thing, but

eek! I was the son of an engineer, and had a beer box full of radio

tubes in the basement. I always ruined my fictional magic by having

to explain it. (Engineers assume that everything cooks down to resistors

at some point and feel obliged to draw the schematics.) She made

hers work by understanding that Magic Just Is.

That wasn't the only gulf we couldn't cross. By my fifteenth birthday

I fancied myself in love with her, but there was something odd about

the feeling that I think she understood a little better than I did.

Once in the thick of a giddy August evening on her back porch I

tried to kiss her—and she ducked. Things got awkward quickly

after that. She told me she liked me better as the friend I'd always

been than she would like me as a boyfriend, and after some inner

grumbling I accepted that. It would be decades before I saw the

research suggesting that the incest taboo is a product of upbringing,

in that unrelated children raised in close proximity from infancy

have an intuitive caution about physical attraction, just as true

siblings do. I think that if I had kissed her that August night,

I would have understood the oddness too. Go back far enough into

childhood, and "childhood sweethearts" just doesn't work.

Evolution knows what it's doing.

Lee Anne died of a brain tumor in 1996. Somewhere in a box I have

what we wrote together of The Timenor, paper-clipped to some

of my notes and a couple of abortive attempts in later years to

keep it going. If I stay on my current trajectory, one of these

years I may yet get a grip on evil cosmic forces or even magic itself,

and then it may be time to pull out The Timenor and see what

happens. Can an engineer just accept magic as it is and not try

to explain it? I keep thinking that if I read (or watch) The

Lord of the Rings just one more time, it'll come to me.

I'm at it again. We'll see. Hang in there, Lee.

|

November

9, 2006: Odd Lots November

9, 2006: Odd Lots

- Slashdot

aggregated an article about brain size and Neanderthal genes,

with all the silly jokes and breathless recriminations that any

such business now generates...but it also gave a name to the bump

that I have on the back of my head: It's an occipital

bun. It's present in some northern European groups, but almost

nonexistent elsewhere. People say we inherited it from the Neanderthals,

which implies that I'm part caveman. Maybe I should make a

Geico commercial.

- My observation of the transit of Mercury yesterday went very

well, and I showed the event to a fair number of people from our

church, as well as a couple of curious passers-by. The small size

of the planet's image caused one woman to remark that she thought

it was dirt on the foamcore sheet. Spectacular, well, it wasn't—but

I was very glad to have seen it, as there won't be another for

ten years. See Pete Albrecht's blog for a

nice photo. Mine were not so good, because the foamcore on

which I projected the Sun's image was a little too shiny. We learn,

we learn.

- One major objection to Flash as a development platform is that

it's proprietary, and while there's some significance in that

(and .NET isn't?) Adobe seems to be doing right right thing to

promote the platform, by

contributing source code for the ActionScript virtual machine

to the Mozilla Foundation. Mozilla will be incorporating the

new source code into the Tamarin open-source ECMAScript virtual

machine, which will eventually make its way into Firefox. It's

not the whole solution, but it's a significant step in the right

direction for Flash.

- Michael Covington pointed me to a link indicating that demand

for $2 bills is increasing, and nobody can explain the trend.

I thought they were extinct, and haven't gotten one in change

in 25 years. One fascinating note in the article describes a wine

shop operator who gives the bills out in change, which makes people

remember his shop. That's certainly a marketing strategy I wouldn't

have come up with myself!

- According to 1960s music expert Kent Kotal, the very first Beatles

single in America was published by Chicago record company Vee

Jay, and was played for the first time in America on Chicago station

WLS by DJ Dick Biondi in early 1963. The single was "Please

Please Me," and it was also significant as the first rock

single I ever bought with my own money. (I was 11 at the time,

and disposable income was a new thing for me.)

|

November

8, 2006: Transit of Mercury November

8, 2006: Transit of Mercury

In just a few hours, today's transit of the planet Mercury across

the face of the sun will begin. It's an event that happens about

13 times per 100 years, though they're by no means evenly spaced:

The last one ocurred in May 2003, but the next one will not happen

until 2016. I'll be out in St. Raphael's parking lot after lunch,

with my vent-pipe junkbox 8" scope projecting the image of

the Sun on a sheet of white foamcore ($4 at Hobby Lobby) for safe

viewing. (I'm going to the church to view the transit because where

I live I have this honking mountain just west of me, and the Sun

will go behind the mountain when the transit is only about half

complete.)

Viewing the transit isn't as simple as viewing a partial solar

eclipse. You can project an image of the Sun through a pinhole and

get the "crescent moon" effect of the Sun with the Moon

partially obscuring it. I've actually projected the partially eclipsed

Sun through the holes in a saltine cracker, and even through a gap

in my hands held together to produce a shadow puppet. (If you're

skilful at shadow puppets you can project the Sun's partially eclipsed

image as the shadow puppet's eye.)

Unfortunately, Mercury is tiny compared to the Sun. It's not much

of a planet to begin with (Mercury's been looking over its shoulder

ever since Pluto got demoted to...not quite a planet) and it's a

long way out there. So while the angular diameter of the Sun is

about thirty arc-minutes, Mercury's angular diameter is only 10

arc seconds, which is only 1/200 as wide. Mercury will thus

appear as a very tiny black dot, and you won't get a sharp enough

image through a pinhole to display it.

If you have a telescope, you can project an image of the sun on

any blank white surface. If you can get a focused image at least

three or four inches in diameter, you shouldn't have any trouble

seeing the planet. If you get a good projected image, do what I

do and just snap a digital camera photo of the projected image.

I did that while observing a group of sunspots back in 2003 and

it worked

beautifully even though a stiff wind was blowing the white cardboard

around.

Obviously, you need to be aware that you should not look through

a telescope pointed at or near the Sun! Close to the eyepiece,

the beam can melt solder; imagine what it would do to your eye.

One additional tip that Pete Albrecht reminded me of: If your telescope

has a finder scope, take it off the main scope before you aim it

at the Sun. The reticles (or crosshairs) in finder scopes can be

damaged if the concentrated light of the Sun falls on them for any

period of time. Also, there will be a beam of light coming out of

the finder that can scorch hands and permanently damage eyes. (The

beam will also be coming out of the main eyepiece, but you'll at

least be aware of that one.) Make sure if kids are around that they

aren't left alone with the instrument, lest they attempt to look

through it!

The transit begins at 19:12 Universal Time, which cooks down to

3:12 PM AT, 2:12 PM ET, 1:12 PM CT, 12:12 PM MT, and 11:12 AM PT.

The transit lasts just under five hours, and I will not see the

end of it here before sunset. Only people on the west coast will

see the whole thing.

I'll post some of my photos tomorrow, as will Pete Albrecht. He has

a bigger scope and much better gear, so don't forget to check out

his blog this

evening. He has a lot of other extremely nice astrophotos posted there.

I don't know if Michael Covington will be posting any photos, but

it's worth checking his

blog as well, since he does some truly spectacular work with his

8" compound scope.

|

November

7, 2006: Communities of Anger November

7, 2006: Communities of Anger

Election Day. God, let it be over soon. I am so sick of

being called by the teachers' unions telling me that our schools

are out of money (they're not) and by the thumpers telling me that

gay marriage will be the end of the world. (It won't.)

If we're really in trouble it may be due to a disturbing trend

mentioned a few days ago in the Wall Street Journal: That

American are retreating into "communities of anger" that

consider any disagreement whatsoever a moral insult, and that our

political discourse (if you could still call it that) is more hate-filled

and poisonous than at any time in our history. It's enough to break

your heart.

As best I can tell, there are two forces at work here, one ancient

and one modern. The ancient one is the two party system, which has

been (mostly) with Americans forever. I have never much liked the

reductiveness of two-party systems, and the enthusiasm with which

many people put a slave collar around their necks and hand their

chains to a political party baffles me. Political parties exist

for one reason and one reason only: To make the world safer for

their largest financial donors. Political parties do not care a

whit for me, and they do not care a whit for you, except to the

extent that our needs align with (and fail to conflict with) the

large organizations that hand them money. Worse, they force their

candidates to the extremes, which is where the big money comes from.

Look at what the Dems did to Joe Lieberman, a centrist whom I think

would have made a pretty decent president, and who could well have

knocked Bush out of the game at halftime, had the dimbulbs on the

lefty fringes given him a chance to run.

As long as there remains some ability in the body politic to see

other perspectives and compromise, a two-party system can work.

But now we confront the modern force: A shrinking ability to conceive

even the possibility that one is wrong, or that a strongly

held belief might not be in everyone's—or anyone's—best

interests. This is what I was leading up to with yesterday's entry.

We have increasingly blind faith in our own unquestionable rightness—and

by implication, the rightness of the political party to which we

(inexplicably) sell ourselves as slaves. When someone dares disagree

with us, our first response is fury, followed by condemnation and

the closure of all discussion.

Where this second force comes from remains a little obscure, but

Jim Strickland suggested sagely that the manic emphasis on "self-esteem"

in our schools may well be one cause—or perhaps the main one.

We are teaching our children not to doubt themselves. There

is tremendous danger in that. The heart and soul of democracy is

compromise, and fundamental to the notion of compromise is acceptance

of the reality that none of us is "right." Every idea

has flaws, no solution to any problem is perfect, and there is no

black and white anywhere except painting and mathematics. Political

problems are not solvable. At best, they are manageable, but in

a democracy management only happens by consensus.

If we cannot doubt the positions that we have taken, then we are

no longer small-d democrats—we are totalitarians. What saves

us here in the U.S. may well be our razor-sharp division into halves

by political party, preventing either party from granting all authority

to its moneyed owners. When the dust settles late tonight, that

division may be even closer. There is some wisdom in crowds. Gridlock

isn't ideal, but it's better than dictatorship.

I keep three principles in mind when contemplating my own position

in the political world, and I offer them to you if you want them:

- I am always wrong.

- The other guy always has a point.

- The answer (if one exists) is always somewhere in the

middle.

Beyond that, it's useful to ask yourself, Who owns me? Unquestioned

loyalty to anything—especially political parties—is unhealthy.

And finally, a truth that everybody seems to have forgotten: Your

apparent IQ is inversely proportional to your level of anger. In

other words, the angrier you are, the stupider you look.

It took me a great many years to figure that out, but it's never far

from my mind anymore, and it has kept me from retreating into a community

of anger, from which nothing emerges but hatred and division.

|

November

6, 2006: Faith without Doubt November

6, 2006: Faith without Doubt

Numerous people have sent me notes since this past Saturday asking

if I'd heard about Ted Haggard, a local pastor at New Life Church,

the largest of several rock-band megachurches that have long been

giving Colorado Springs a bad name among secular folk. Well, uh,

yeah. It's about the only thing there was in Saturday's paper, and

has dominated local news ever since then. Quick summary: One of

our noisiest and most self-righteous local Bible-thumpers was caught

having sex with a male prostitute out of Denver, and admitted that

he'd been paying this guy for sex for three years. Oh, and

then it came out that the same guy sold Haggard some meth, which

Haggard insisted he never used. Boy, where have we heard that

before?

It's true that Haggard is human, but he's also a religious leader,

and I don't think it's unreasonable for us to have much higher

standards for religious leaders than for ordinary people. I've been

saying for years (basically since the Roman Catholic clergy abuse

crisis blossomed) that religious leaders (clergy or lay) who cannot

control their appetites must resign now, and work on their

own inner demons before trying to help others with theirs. Crying

"fallenness" is no excuse at all. Most of us who haven't

spent years in divinity school are perfectly happy being faithful

to our spouses.

One has to ask why these periodic meltdowns of prominent religious

leaders happen at all. One obvious reason is that born leaders (especially

male leaders) tend to have ravenous sexual appetites. But it isn't

always about sex; it can be about drugs, power, or (especially)

money. I think there's another issue here: Faith without doubt.

People who work relentlessly at removing any least shred of doubt

from their faith in God don't always notice that the same effort

removes doubt from their faith in themselves, and can cause them

to subconsciously make excuses for their own nasty behavior, often

without realizing what's going on. In my lifelong struggle with

religion, I've learned a number of things, and tops on the list

is that "blind" faith (that is, faith without doubt or

examination) is absolutely deadly.

Faith is not effortless, and it is not automatically any source

of comfort. Quite the contrary: Faith is almost by definition life's

supreme challenge, and that challenge is the engine by which we

grow spiritually. Inherent in that growth is doubt. If you don't

doubt that you have flaws that need work, you will deny them, hurt

others, and continue being a selfish, hurtful shit. A mindset that

cannot doubt anything about one's religious framework or culture

tends not to doubt one's personal integrity, either.

There's nothing wrong with doubting the existence of God, nor certainly

doubting the details of any given religious tradition. God will

get you sooner or later; C. S. Lewis called Him "the Hound

of Heaven," and I don't think He requires adherence to a particular

religious tradition so much as being pointed in the right direction.

(That direction being one of mercy, kindness, and generosity.) Being

pointed in the right direction requires self-examination and self-doubt.

If you never question the validity of your picture of God nor the

religious framework within which you live, you will not grow, and

you will end up stale, aching, and empty. Certain personality types

have a tendency to turn that inner emptiness into rage directed

at others, and there's where a great deal of toxic religion comes

from. I've run into a few reactionary types in the far corners of

the independent Catholic wing of Christianity, and they were for

the most bitter, angry men who had no ability whatsoever to doubt

themselves. Alpha males, Right Men, whatever you want to call them,

they are dangerous people, not only to themselves and their loved

ones but to their religious traditions and the very idea of religion

itself.

I doubt every last detail of my own religious tradition, and yet I

keep returning to it. Am I nuts? No. Am I a heretic? Hardly. I think

that's just how faith works. The more you doubt it, the more you understand

it, and the more you understand the vastness of the challenge that

faith represents. If you continue to feel that it's worthwhile (a

separate discussion) the effort can transform you, and that's ultimately

what faith is about.

|

November

5, 2006: Who Needs a New Computer? November

5, 2006: Who Needs a New Computer?

Carol and I were down at Otho's yesterday and Christmas muzak was

playing instead of their usual saxaphone jazz. Oh, well. Halloween

is over and for whatever reason, Thanksgiving doesn't have much

traction with the American imagination anymore.

But right on schedule, Slashdot aggregated a

(weak) article this morning, saying what we hear almost every

Christmas season: PC sales will be weak, for a list of ridiculous

reasons: exploding batteries, waiting for Vista, yadda yadda yadda.

Nobody seems willing to admit the obvious: For the overwhelming

majority of consumers, PCs purchased two or three or even five or

six years ago are still perfectly usable, especially if they don't

have multiple malware infections and have undergone a little degunking

to reduce Windows entropy.

One of my ministries at our parish (though I still grin a little

thinking of it as a ministry) is helping parishioners out with their

PCs. I have helped a few make the jump to new machines, often from

doddering wrecks that they have owned for ten or twelve years.

But mostly I just help them get back on track after being derailed

by malware or accumulated gunk. I see a lot of 1999-2002 era machines

running Office 97 and little else. I install Firefox and sometimes

Thunderbird for them (as well as a firewall if they don't have one)

and they're off with a roar, happy as can be.

Even I get three or four years out of a machine, and in fact I

still have in almost daily service my primary boxes purchased in

1998 and 2002. A lot of my software dates back to 1999 and 2000.

It does what I need, and on a 3 GHz machine with 4 GB of RAM, that

old stuff really rips. I bought an XP system because a guy in my

line of work needs to know XP, but my daily operations are still

conducted under Win2K because I will not allow a computer to hold

my work hostage.

We're on a plateau. The "user experience" is generally

pretty good. Even non-enthusiasts have had time to get used to Windows

and the general concepts behind Windows computing. Their machines

do what they need to do. PC lifetimes are stretching out, and I

think we hit a sort of sweet spot in or about 1999. There will be

Win2K and XP boxes running unmodified for another fifteen years,

or even more.

Geek tho I may be, I still have a 1995 minivan in my garage. Still

works. Coupla rust spots, but hey—it's paid for. Why do computer

companies assume they can push a new box down everybody's chimney

every two years?

|

November

3, 2006: Odd Lots November

3, 2006: Odd Lots

- Much going on here, and I may not be publishing Contra quite

as often as in previous months. A lot centers on preparing materials

for Lulu, which I'm going to be testing in a number of ways. I'm

also testing a new scanner designed specifically for scanning

books and magazines, and will report here once I've gotten a good

feel for it.

- I got a Skype spam the other day, and (worse) it was a 419 scam

from South Africa. The instant the message arrived, the sender

was offline, clearly to avoid being traced. Although Skype can

block senders, it's pretty obvious that that message would not

arrive from that same sender again. Conventional spam is also

up, and nearly all of the additional spam is pump-and-dump stock

scams, which may well be the perfect crime.

- I'm increasingly convinced that Flash is hugely superior to

AJAX as a Web 2.0 platform. Check out calendar/organizer

app Scrybe, a Flash app that (admittedly) is not yet generally

available—but play the video. Egad. I don't know about

you, but I find that extremely impressive, especially since

Scrybe works when you're offline, and will seamlessly sync with

your server-side data as soon as you connect.

- There is a

transit of Mercury this coming Wednesday. While not as vanishingly

rare as a transit of Venus, it's still uncommon, and worth watching

if you have the usual solar eclipse paraphernalia. The transit

will be seen in its entirety only from the westernmost quarter

of the US; east of there, the sun will set before the Mercury

completes its run across the solar disk. Here in Colorado, we'll

get most of it, though the transit will end shortly after sunset,

and the presence of mountains on our western horizon makes things

a little complex. I'm heading about five miles east to our church's

parking lot to get away from Cheyenne Mountain, and will have

my 8" scope projecting an image on foamcore for anyone who

wants a look.

|

November

1, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 3: Plot November

1, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 3: Plot

We are storytelling creatures, and I have an intuition that language

evolved in parallel with storytelling as a survival skill: Relating

where the game can be found, impressing women (and rivals) with

your badass exploits, and so on. Kids are really good at creating

stories, for entertainment, bluster, or to shift blame. ("The

dog ate my homework!") So fashioning plots may be at once the

easiest and the most difficult part of designing novels: Easiest

because it's in our genes; and hardest, because it's so deep in

our genes that it's difficult to control.

The way I plotted The Cunning Blood (and most of my earlier

fiction longer than a few thousand words) was simple, effective,

and occasionally infuriating: I created a broad concept, vividly

envisioned an opening scene, then cast wide the gates and let 'er

rip. The details of the plot (almost) always emerged in a form that

would both gibe with my broad concept and move the story in a useful

direction.

The broad concept often begins very simply, and for The Cunning

Blood went something like this: Peter Novilio and his nanocomputer

partner the Sangruse Device are sentenced to transportation to Hell,

and Peter is offered a pardon if he can go down there and come back

with useful information on what Hell is up to. While there he uncovers

a plot to topple Earth's world government. End of plot outline.

Going in, that's literally all I had.

It grew quickly, of course, but what I found amazing is how much

of the plot detail showed up in a "just-in-time" fashion.

Every so often I had to think hard about what would come next, but

in most cases the ideas that would become the plot for Chapter X+1

came flooding in just as I was wrapping up Chapter X. Late in the

book, when the action was no longer linear in a single thread, I

had to take a couple of time-outs to sketch out sequences of scenes.

(One such timeout was a very memorable autumn walk in Seattle with

my close friend Michael Abrash.) But while I was writing a single

thread, the details came to me as I needed them.

Every once in awhile the chipper/shredder in the back of my head

spat out a dead end. This happened twice in The Cunning Blood,

and I had to backtrack and scrap about 10,000 words. One chapter

scrapped was just plain bad, although it had coalesced around an

interesting idea. (I may use the idea in the sequel, if I write

the sequel.) The other was a door to perhaps another 100,000 words

of story complication, and I was already well past my first 100,000

and looking for an ending. I'm always annoyed when I have to delete

text, but it was encouraging how easily my subconscious picked up

the scent again with a little conscious prodding.

I'm a sample of one, and it's hard to generalize strictly from

my own experience, but I have noticed that it helps to visualize

early scenes as cinematically observed, and not just textual descriptions

in a note file. That means just what it sounds like: Create a

movie in your head and watch it. The first scene in The Cunning

Blood as I originally wrote it had a heavily-armed assassin

stalking Peter Novilio in an ancient graveyard. (The first scene

as published was written later and added as a kind of prequel to

give the reader some bearings.) I envisioned the graveyard right

down to the crumbling walls and the glints of light on polished

headstones, and I spent some significant time leaning back in my

chair and following an imaginary video of Peter playing cat-and-mouse

with his assailant. There is a strong visual component to our storytelling

faculty. You have to see the sabre toothed tiger before you

can spin the yarn of how you outsmarted it.

Those stories for which I didn't create a cinematic vision of the

first scene tended to be static and talky, and most failed or weren't

even finished. There's something absolutely critical about literally

seeing the first part of the story in your imagination. If you can

do that, the genetic story machine we all carry with us will do

most of the rest. It may even be true that people who can't write

fiction fail because they have insufficient ability to visualize

a scene in full action. In other words, they could write it if they

could see it, but they can't see it.

To summarize my method (if you can call it that) for plotting:

- Create a broad concept for the plot. Think of it as a bounding

box for the action that frames the story. Don't be too specific;

again, you need to give your subconscious plenty of room to move.

- Whatever it takes, imagine the first scene in full cinematic

action, and run it through your head a few times, adding details

as you go. This doesn't require that you be writing an action/adventure;

you can envision two people walking home from the grocery store.

But envision them richly. My story "Bathtub Mary" opens

on a summer evening, as a blind woman walks home with an intelligent

computer pinned to her lapel. Very little action, but I had the

woman, the street, the pavement, the houses, and even the weeds

along the roadside in utterly crisp vision. The story worked,

and worked well, even though there's almost no physical action

in any of it.

- Start the story by describing that initial scene, and pay attention

to new visual clues that begin to emerge from your subconscious.

If the clues falter, stop where you are and rev up the theater

of the mind once more, with feeling.

- If you get really stuck, do some research, take a walk (I find

that moderate physical exercise revs the idea machine) and play

some music that strikes a deep emotional chord in you. The music

needn't have any connection to any aspect of the story, though

there are sometimes resonances. A cut called "The Plagues"

from the soundtrack of Prince of Egypt helped me envision

the scene in which Sahan Grusa levels the pirate colony Columbia

by creating frightening (but harmless) fantasy creatures as nanotech

macrobots, much like God raining frogs and such on Egypt. It sounds

silly, but it worked.

- Don't give up if things fall apart in any given session. You

may be distracted by the things of this world, so set aside your

imaginal world for a night and come back to it fresh the next

day, ready to see it in motion in your mind.

Plotting is really the core of the storytelling art. You need gimmicks

and characters, but without plot, well, they're just ideas. Strive

to be a visual person, and don't just sit at home all the time.

Go out and see what animals and mountains and machinery actually

look like. Travel. Experience. Like the commercial says, live richly.

Imagination builds on the real.

It's November 1. I've told you what I know. Now

get out there and write us a novel!

|

|