|

|

|

|

October

31, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 2: Characters October

31, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 2: Characters

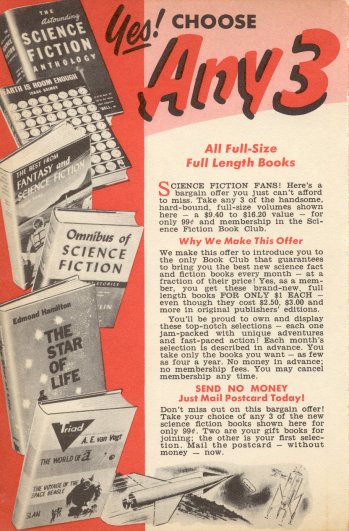

There was a time when characters didn't matter much in SF. The

gimmick and the plot were primary, and the characters were named

shadows that moved with the plot like wood chips floating downstream.

A lot of the pulp fiction from the 40s and 50s that we now consider

unreadable is unreadable for that reason: The hyperdrive is on,

but nobody's home.

Although an occasional reviewer will plaster a book for being boring,

most of the complaints lodged against modern SF have to do with

characters, and what this tells me is that people are now looking

for characters more than gimmicks or situations. There's a serious

danger here, in that characters without interesting backgrounds

or anything to do basically become soap opera, and a great deal

of modern SF is costume soap opera, especially series fiction. Situation,

characters, and plot are all essential, and in the finest fiction

they are woven seamlessly together in a way that makes you gasp

when you spin past the last page, wishing it would go on. Of course,

one thing that makes good fiction good is that it knows where to

stop, even when the readers are left aching for more. The only thing

worse than not getting what you want in this case may be getting

it.

Alas, nobody's equally good at everything. I'm as bad at crafting

characters as I am good at coming up with tech gimmicks. Nonetheless,

I've found that I've become better with practice and conscious direction

of the characterization process. I need to say here that most of

what I know about characterization I learned at the knee of SF writer

Nancy Kress, who lived nearby and was a close friend when we lived

in Rochester, New York 25 years ago.

Human characters are simulations of human beings. (Most SF aliens

are human beings in rubber suits, which is one reason I don't have

many aliens in my fiction. Like, almost none.) They have strengths,

passions, weaknesses, and personality quirks. You have to be aware

of all of these, and keep a character's actions in line with the

personality that the reader is given to understand. Good characters

grow with the action of the story, as they bump their heads on plot

twists and their own limitations, and that may be the toughest aspect

of characterization that you'll face.

What I have learned to do, and which works well for me, is to create

a sort of character dossier for the most important people in a story.

Basically, you sketch out a character's personality. This is not

what the person does, but what that person is. It

doesn't take a lot of words to do this, and in fact if you run on

too long you can get in various kinds of trouble. Here are a couple

of dossiers from the novel I'm currently working on, The Anything

Machine:

Howard Himmel Banger:

Age 14, son and only child of Stella Price Banger. Average height,

muscular, shaggy brown hair. Has an inborn talent for pictorial

art and illustration but is unsure what sort of career to pursue.

Geeky and systematic, he likes to categorize and sort concepts.

(His mother is pushing him toward an information science career

in content management; basically, to be a librarian.) Prone to

nightmares after his father was murdered when he was only seven.

A little selfish, less emotionally mature than Gustavia. Not especially

confident except when pursuing his passions, and then he approaches

mania. Has known Gustavia since they were toddlers in SUNY faculty

daycare, and assumes that she will spend her life with him, whether

they manage to return to known space or not.

Gustavia Marya "Gusty"

Kowalczyk:

Age 14, daughter and youngest child of Gustav and Anna Kowalczyk.

Short (5'4"), thin, blonde, athletic, gray eyes, pretty without

being dazzling. Intends to pursue degrees in economics and business

and then teach at SUNY Numenor. Willful, very focused on her studies

and her career, and careful lest she make a mistake that will

impact her future. Fascinated by animals and the business of agriculture.

She struggles with her feelings for Howard, torn between her awakening

hormonal attraction to him and her fears that he will not take

the place she has outlined for him in her plan for her own future.

The danger in writing character dossiers is not too little but

too much. The idea is partly to seed your subconscious machinery

with the outlines of a character, and in part to have something

to measure a character against as a story unfolds. Both functions

depends on how your own subconscious mechanisms work and how you

manage them. Characters have a well-known tendency to "grow

away" from your original conception of them. This can be a

problem, but it can also be borderline miraculous. For example,

my early plot outline of The Cunning Blood had no major character

named Jamie Eigen. Jamie was at first a nameless spear carrier,

a sounding board for Peter while he was in jail. But my subconscious

clearly had other plans, and Jamie quickly evolved into perhaps

the single most pivotal character in the whole yarn.

Too much detail in a dossier can lead to conflict between what

your subconscious wants to do with a character and how you consciously

perceive that character. It's best to leave a character dossier

a little bit sketchy, so your subconscious mechanisms have room

to move. Yes, that's a tightrope walk, and you'll have to zero in

on the sweet spot through practice. Again, my intuition is that

it's better to say too little in a dossier than too much.

Avoid the temptation to include in a dossier what characters do.

Howard discovers the Thingmakers, and creates an index that later

evolves into Banger's Big Book of Drumlins ("drumlins"

being artifacts produced by the mysterious Thingmakers) but those

are plot elements, not character aspects.

Nancy Kress always told me that it's important to understand what

each character wants. This is implied by a good dossier,

but sometimes it's useful to look at a character from an extreme

height: Young Gusty Kowalczyk wants life to be predictable; young

Howard Banger wants life to make sense. Most of what they do (and

much of the conflict between them) follows directly from those high-level

differences. If you can understand your characters that deeply,

you can probably do good things with them. So far I'm having a lot

of fun, and the story (which is a juvenile; a first for me) is evolving

well.

More next entry.

|

October

29, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 1: The Gimmick October

29, 2006: Designing Novels, Part 1: The Gimmick

I've been meaning for some time to talk a bit about the process

by which I design novels. I don't claim that this is the only way

to make a novel, but it's the way my stories come together in those

odd back-of-the-head places that I can only barely perceive.

And that's a good place to start: Novels are emergent processes.

You don't design one quite the same way you design an electronic

circuit. From my experience with my own work in novels (I've written

several, though only one is published) and from talking to other

people who do it, something like this happens: You toss a certain

number of consciously designed elements into the chipper/shredder

in the back of your mind, and then you open the gates to see what

comes out. Some people toss more consciously designed elements into

the chipper than others do. Some people just start writing, and

after a few thousand words take a break to see if what has emerged

has any value or is just incoherent mulch.

I've tried it both ways, and at many points along the gradient.

As usual, there's a sweet spot in the spectrum, where the degree

of conscious design is just enough to feed the individual characteristics

of the mad chipper/shredder operated by your subconscious. Too much

design, and the chipper gums up and the process grinds to a halt.

Too little, and the chipper spits back incoherent blather that never

coalesces into anything you could call a story with a straight face.

Where do you start? I always begin with what a call The Gimmick,

though many call it The

McGuffin. I don't like the term "McGuffin," because

it implies something that advances the plot without being especially

relevant to it. A good gimmick lies at the very core of all the

conflict that besets your characters, and it may well be the thing

that your readers remember years after reading the story. Gimmicks

are extremely important in SF and often in fantasy as well. (Literary

fiction generally dispenses with gimmicks entirely, and relies completely

on characterization.)

The gimmick in The

Cunning Blood is not so much the Sangruse Device (an intelligent

nanocomputer) as it is a planet where electrical things don't work.

They don't work because of a bacterium-sized nanodevice that homes

in on the magnetic fields generated by electrical currents of useful

intensity, and breaks down the metal of the circuit's conductive

elements until the current stops flowing. Earth authorities (who

designed the nanodevice and turned it loose on a nearby Earthlike

planet) assume that this condemns those who live on Hell to a sort

of pseudo-Victorian gaslight existence. What they forget is that

there are more paths to high technology than the electrical ones

that Earth followed. Diesel engines, chemical lighting, photochemical

amplifiers, mechanical and fluidic computers, fiber optics, they're

all in there—and they're all real. Where electricity is crucially

important, the Hellions use wires consisting of liquid mercury in

thin hoses. The current-sensing nanomachines can't disrupt liquids.

I could have spun a lot of stories around that one gimmick, and

I may do one or two more. The point is that it's a good gimmick,

and a memorable one. I put a lot of energy into researching it,

and many people have told me that Hell sounds completely plausible

and real to them.

You come up with gimmicks by paying attention to the physical world.

I read a lot of science, a habit I got into when I was in high school,

and Isaac Asimov was publishing a fat paperback full of fascinating

science essays every few months. I had a nose for the odd corners

of science and technology, especially the ones that never made it

into the mass market. Popular Science ran an article about

fluidic computers when I was in high school. I read as much about

Babbage's mechanical computers as I could as soon as I heard about

them. You do this for a few years, and stuff starts to precipitate

out of that mass of intriguing facts in the back of your head.

I keep a notefile of gimmicks, and add to it when odd things occur

to me. Could an astrobleme

have such high walls that the atmosphere would be different inside

the bleme than outside? I think so. It's a gimmick. I may never

use it, but it's intriguing. Could hacked bacteria separate isotopes

of metal salts dissolved in seawater? I don't see why not. Not every

gimmick is big enough to hang an entire novel on, but there's no

law saying that a novel can only have one gimmick.

Once your gimmick is in hand, you have two ways to go: You can start

playing what-if, to see what would happen if the gimmick were made

real and turned loose, and then build a plot around the consequences.

Or, you can design a cast of characters and see how that gimmick might

affect them, which would then suggest a plot. Stories have been done

both ways. We'll talk more about that in my next entry here.

|

October

27, 2006: Duntemann's Brain October

27, 2006: Duntemann's Brain

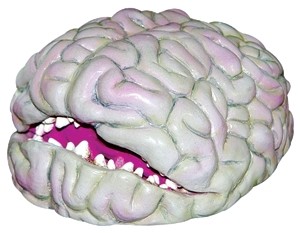

My

sister Gretchen just sent me what may be an early Christmas present:

A slightly squishy, crawling, humming, snarling audioanimatronic

plastic brain...with teeth. It arrived an hour ago and was not anticipated,

but it's been a lot of fun. My

sister Gretchen just sent me what may be an early Christmas present:

A slightly squishy, crawling, humming, snarling audioanimatronic

plastic brain...with teeth. It arrived an hour ago and was not anticipated,

but it's been a lot of fun.

It senses nearby motion and sound, and when triggered, it hums

a manic little tune for several seconds while crawling forward about

a foot. Then it stops, opens its mouth, and starts snarling and

slobbering.

We instantly knew what to do with it: We turned it on and put it

down on the floor. QBit bent down to sniff it (I'm sure he was wondering

which end to sniff and why there wasn't a tail to sniff under) and

when he set it off, he jumped two feet straight up. A second try

evoked the same response, and since then he gives it a doleful look

from a considerable distance.

We've named it Duntemann's Brain, and it will actually earn its

keep around here. QBit has become a very avid table surfer, and

any time neither of us is in the room, he will hop up on the kitchen

table and start licking the spots on the placemats where I've spilled

spaghetti sauce or chicken soup. Then he jumps down with one or

more placemats in his mouth, and will drag them off to his lair

under the bed if we don't catch him first.

Simply put, Duntemann's Brain will become our kitchen table placemats'

bodyguard. In between meals, it will sit there to one side of the

salt shaker, waiting for QBit to mount the table. Our only concern

is that he will break something trying to get away when it goes

off and starts humming and snarling.

Thanks, my good sister. This one's a keeper. Now, who will hack the

mechanism to make it sing "Let There Be Peace on Earth"

or "I Ain't Got No Body" instead of humming?

|

October

26, 2006: What Sells on Lulu? October

26, 2006: What Sells on Lulu?

Test Prep. Programming. Diets. Dogs. Lately, a technical manual

for the 737 airliner. Almost anything but fiction.

It was a useful ten minutes I spent earlier today, studying the

top 100 sellers on Lulu.com, the print-on-demand and digital

content gumball machine that I'm going to be using for a number

of projects in coming months. Some thoughts:

- Nonfiction rules. Of the top 100 books, I count only six

that are fiction, including one written by a nine-year old. Admittedly,

#5 and #10 are fiction, but the next tale down is #45, and the

last three are all south of #80.

- Most of the books have competent or even professional looking

covers. It's impossible to know how they came by their covers,

but I was expecting a lot of pastel cardboard with words on it.

Not so. Good photography, good design—it makes me wonder

how many of these books are "long tail" reissues of

books originally released for the retail store market with professionally

designed covers.

- Many of the topics are things I would consider useful, if not

for myself than for at least a significant if small audience.

Examples: That

Military House: Move It, Organize It, and Decorate It.

Nobody moves more often than military folk. This book is a natural.

Or: Intermodal

Shipping Container Small Steel Buildings.

How to make buildings out of used shipping containers. Hey, if

you need to do that, you need this book bad. Or: Plone

Live; basically, a user guide for the Plone content server.

There's a fair bit of whacko stuff in the top 100; typical of

which is How to

Become an Alpha Male, dubbed "The lazy man's way

to easy success with 20 or more women a month." (Good lord.)

But I was amazed at how reasonable and practical most of the top

100 nonfiction titles were. Narrow, yes. (There's an entire

book devoted to helping Catholics resist the temptation to

masturbate!) But—heh— practical.

- There's not much turnover at the top. Lulu has a "this

week, last week" display that shows how the top 100 titles

have changed rank, and (for the most part)...they don't. What

was #1 last week is #1 this week. Indeed, of the top 30, only

two books changed rank at all. (#5 and #6 changed places.) Most

books change rank by one or two positions only. The big exception

is The Boeing

737 Technical Guide, which is up 27 positions this week.

Consistent ranking over time suggests consistent sales. We aren't

told what the absolute numbers are, but I suspect that they're

constant, if modest.

I'm pleased with the way Lulu works. It looks like people are having

some success with it. Again, this is what the future looks like for

niche publishing. I'm going to try uploading a book there tomorrow.

Cross fingers. I'll keep you informed.

|

October

25, 2006: Lulu as a Digital Gumball Machine October

25, 2006: Lulu as a Digital Gumball Machine

I don't think I've talked about this yet, but having researched

them in some detail, Lulu is

probably the closest we've yet come to a digital "gumball machine."

You can publish an ebook (or any kind of digital content, including

music, photographs, or software) on Lulu, and simply pay them a

20% commission on each copy sold. No other charges. Most other services

that I've researched take a lot more than that; some over 50%. The

effective minimum charge per item is $1, on which Lulu takes 20

cents. You can charge less than a dollar if you want, but the commission

remains at a minimum of 19 cents.

Costs are a lot higher if you want them to print and fulfill paper,

of course, so I'm wondering how many people would be willing to

buy an ebook laid out for 8 1/2" X 11" pages, and then

print it locally. I've been asked to write an article about my

homebrew 2-tube 6T9 stereo amplifier, and if I did I might do

it that way: A 24-page booklet with schematics, photographs, and

detailed instructions, including a parts list with where to get

the parts. You could either read it from your screen or print it

on paper so it could lie flat on your workbench. I'd sell it for

$2 on Lulu, and make $1.60 on each download. I'd be happy with that.

The research is long done, the schematic is already drawn, and writing

is easy for me. If I made $100 lifetime on it I'd be happy.

Lulu seems to be doing well, and once the world at large understands

that they're doing well, there will be competitors, and author costs

will go down. We may finally be coming to a day where niche publishing

can actually make money. I'm close to getting my first title mounted

on Lulu, and you'll read all about it right here.

|

October

24, 2006: Another Unknown Earworm Captured October

24, 2006: Another Unknown Earworm Captured

One of the great unsolved problems in computing is what they call

"query by humming;" that is, the recognition of melodies

based on inexact reproduction of those melodies. Google has allowed

me to hunt down a great many odd things, like the old "Elmer

the Elephant" kids' show in Chicago, or "Video Village,"

one of the first modern TV game shows, which was Monty Hall's debut.

However, it won't help me with a handful of catchy melodies that

I have tucked away in the back of my head, some dating back a long

way.

I caught one of these "earworms"

recently, though it wasn't easy, and didn't depend entirely on the

melody. When I was very young (figure late 1950s) I remember seeing

a musical cartoon on one of those ancient Saturday morning "cartoon

shows" that had no host or anything but people at the TV station

putting on one old theatrical cartoon after another. The cartoon

I was thinking of was a mixture of animation and live action, with

a real guy playing the piano, and a stop-motion animated big-eared

gremlin dancing around on the piano to an extremely catchy

jazz tune.

What allowed me to catch the earworm was a single memory: At the

end of the cartoon (or maybe the beginning) was the word "Puppetoon"

in large letters. Google took that and led me to George Pal, who

was also the major force behind the special effects in the seminal

1950 film Destination

Moon. (Chesley Bonestell did the background matte paintings.)

George

Pal created an animation technique we now call "replacement

animation," in which the animators basically create an

erector set of different body parts in different positions for an

animated character, and reassemble the character for every (or almost

every) frame. He did a whole series of Puppetoons using this technique

for Paramount in the 1940s, including a couple of pretty famous

ones, like "Tubby the Tuba" and "John Henry and the

Inky-Poo." I poked around on Google through lists of the numerous

Puppetoons. One of them, "A Date with Duke," featured

Duke Ellington, a master of jazz piano, which seemed promising given

the jazzy piano soundtrack. Sniffing around links containing "A

Date with Duke," I landed on this

page, and there it was: The

dancing gremlin that I remember clearly. (The rightmost of the

four stills.) George

Pal created an animation technique we now call "replacement

animation," in which the animators basically create an

erector set of different body parts in different positions for an

animated character, and reassemble the character for every (or almost

every) frame. He did a whole series of Puppetoons using this technique

for Paramount in the 1940s, including a couple of pretty famous

ones, like "Tubby the Tuba" and "John Henry and the

Inky-Poo." I poked around on Google through lists of the numerous

Puppetoons. One of them, "A Date with Duke," featured

Duke Ellington, a master of jazz piano, which seemed promising given

the jazzy piano soundtrack. Sniffing around links containing "A

Date with Duke," I landed on this

page, and there it was: The

dancing gremlin that I remember clearly. (The rightmost of the

four stills.)

The soundtrack for "A Date with Duke" was Ellington's

own "Perfume Suite," which I researched, and found to

contain several movements. I researched each of the movements in

turn, trying to find somebody with a sample I could play. The first

few I movements I found samples for were too slow to be the tune

in question. Then I went after "Dancers in Love: A Stomp for

Beginners." The first sample I found was, somewhat oddly, played

on classical guitar. It seemed right but I wasn't sure; the

part of the melody I remember most clearly wasn't there. After much

additional poking around, I finally got here,

and played the WMA28 sample of "Dancers in Love." Bingo!

That was it! I still haven't found the cartoon—it would be

fun to see Ol' Big Ears dance again—but at least I was able

to nail a CD of the music itself.

So. Whythehell does it have to be so hard? Why can't I just whistle

the melody into my headset mic and let an algorithm name that tune?

It took over an hour of detective work (though I will admit, I learned

a few things, as I always do during that kind of detective work) and

the detective work had very little to do with the melody itself. David

Stafford says it's a very difficult problem to solve, and he's solved

some doozies. Sooner or later, however, it's gonna fall. Let's hope

it's within my lifetime; that's one earworm down, but there are still

a few more knocking around in there.

|

October

23, 2006: Why Executive Salaries Can Explode October

23, 2006: Why Executive Salaries Can Explode

I've begun to see a great many head-scratching articles about the

explosion of executive compensation in the last eight or ten years,

especially at very large corporations, while general staff compensation

has stagnated or dropped. The puzzle is why people are puzzled;

it seems pretty damned obvious to me. Three forces are at work here:

- We have gone from a general labor shortage in the developed

world to a general labor surplus. Demand for labor peaked right

after WWII, and now supply has caught up with demand. This may

not be cyclical but structural, in that the demand for labor post

WWII was a one-time consequence of industrialization leading population,

at least in those places where industrialization was happening.

Because labor markets are truly markets, compensation for workers

outside the executive suite is dominated by the effect of this

labor surplus.

- People at the top of large corporations in effect set their

own salaries, because corporate boards, which set executive compensation,

are composed almost entirely of other highly-paid executives or

retired executives. They look at executive compensation questions

and see their own interests in their answers. Nor do the numbers

I see indicate that higher executive pay yields higher financial

performance of the corporation as a whole. The market doesn't

work here.

- Although CEO compensation numbers seem high to the rest of us,

compared to the overall revenues of massive corporations, a few

or even many millions of dollars is small change. Paying the CEO

fifteen mil a year won't crash the company, and dropping CEO pay

to, say, one or two million a year wouldn't help the company,

if revenues are in the billions. On the flipside, when you have

tens of thousands of employees, giving them all a significant

raise could cost a hundred million dollars or more, which would

affect overall corporate viability.

None of this makes it right; it just explains how it's possible.

And that said, the curves are not moving in the right direction:

Revenues generated by continuing productivity gains are flowing

toward the top in an ever more concentrated fashion, probably because,

with markets controlling labor costs, it's easy for them to do so.

I don't know what the answer is. I like game theory solutions to problems

like this, and one suggestion might be to set corporate tax rates

by algorithm, where the lowest tax rates apply when total compensation

dollars spent are most broadly distributed across all employees. I

doubt that that's politically possible, but it's an interesting notion,

and might encourage closer monitoring of executive compensation by

shareholders.

|

October

22, 2006: Gouache, Tempera, and Elmer's Paint October

22, 2006: Gouache, Tempera, and Elmer's Paint

I inherited a lot of things from my mother, but her intuitive knack

for fine arts (she painted well and worked in ceramics) didn't come

down to me, dammit. So apart from a short no-credit "enrichment"

course in college that exposed me to silk screening and acrylics,

I have almost no experience in painting. So while it's still unclear

what sort of paints were used to paint the very early covers in

Popular Electronics (see my entry for October

20, 2006) I learned a great deal about artists' paints by fielding

the resulting email traffic. Consensus is that they're not classic

watercolors, and may be one of the following:

- Tempera is a species of water-based paints using a binder

made of egg yolk. Tempera doesn't allow the sort of deep color

saturation that oil paints or acrylics do, so it can superficially

resemble watercolor. If I had to guess what Ed Valigursky was

using on those old PE covers in 1955, this would be it.

- Several people suggested gouache, which is a denser but

much crankier species of watercolor, in which the pigment particles

are larger and there is less water in the paint. Gouache is more

used in geometric Miro- or Klee-style paintings or posters than

in classic "fine art" paintings in which individual

brush strokes combine to form a holistic image. The nature of

gouache paints require that they be used quickly, suggesting a

presence in commercial art. However, the drying process affects

the appearance of the pigments peculiarly, and they are notoriously

hard to control across multiple painting sessions.

- George Ewing was the only one to mention casein paints,

which amount to pigmented and slightly thinned out Elmer's Glue

based on a casein binder extracted from milk. I had never heard

of these, but research indicates that they have been used since

the time of the ancient Egyptians. They cover completely and can

be as deeply pigmented as oils.

Michael Covington pointed out that shiny paintings are much harder

to photograph than paintings having a matte finish, so commercial

art would be more likely to use a non-oil process like tempera. Sooner

or later I'll hear from an older commercial artist who can nail the

question. We'll see.

|

October

21, 2006: Odd Lots October

21, 2006: Odd Lots

- The cap I mentioned in yesterday's entry is apparently a US

Army M-1951 field cap (more formally, the "Cap, Field, Cotton,

Wind Resistant, Poplin, M-1951") or perhaps a WWII German army

M-43 or M-41 field cap, which look pretty much the same. The M-1951

was used from Korea well into Vietnam, when it was retired in

favor of a military ball cap. It's unclear whether the Americans

or the Germans invented the cap, though I think it may well have

been brought here from a galaxy far far away, where it was standard

dress for Empire starship drones. The cap recently re-appeared

as part of the Army's BDU (Battle Dress Uniform) though apparently

only in camo. Thanks to Robert

Bruce Thompson (and several others) for putting a name on

it, after which Google did the rest. I like the fold-down ear

flap, which could be real handy up here in the mountains.

- Also pertinent to yesterday's entry, the cover artist on those

Popular Electronics covers was Ed Valigursky, who was a

very popular SF cover artist in the 1950s and early 1960s, and

also did covers for Argosy and Saga. No surprise

where that square jaw came from, heh.

- Karen Cooper says that the covers (again, from yesterday's entry)

are not watercolors, and, being an artist, she has some reason

to know. I don't think they had acrylics in 1955, and although

I'm innocent of art training, I do know that oil paints take a

long time to dry—certainly longer than the lead time most

magazines give artists for cover art. (I do know a little about

that.) Maybe pastels?

- For years I've been seeing little lines of symbols on clothing

tags (especially my shorts) without ever becoming curious enough

to go figure out what they meant. Finally (only a few hours before

Carol came home from her recent two-week trip to Chicago) I got

crazy enough to care, and here's Your

Guide to Fabric Care Symbols. Just FYI.

- Scientists at Indiana University have discovered what may be

the

first living things for which radiation is an essential part of

their metabolic cycles. A colony of bacteria discovered two

miles below the surface in extreme northern Canada relies on natural

radiation (from uranium deposits) to split water into hydrogen

and oxygen. The bacteria then use hydrogen to release chemical

energy in reaction with local sulfur-bearing minerals. How the

bacteria managed to make their way down into several miles of

rock is an interesting question, but the implication is fascinating:

Living things can evolve to harvest almost any source of energy,

and if they can do it under two miles of Canadian rock, they can

do it anywhere.

|

October

20, 2006: Popular Electronics in Watercolor October

20, 2006: Popular Electronics in Watercolor

As I've mentioned here, I've been gathering up old issues of Popular

Electronics to complete my collection, mostly off eBay. The

other day I got a very nice batch, most from 1955 and 1956, a time

when I was still struggling to keep pieces of fish stick on a fork,

and had not yet begun building things in cigar boxes. (That time

wasn't far off, though.) What was nice about this batch is that

it had clearly been stored all these years on someone's bookshelves,

and not out in the garage under a tarp held down by half-empty cans

of paint in bad 50's colors.

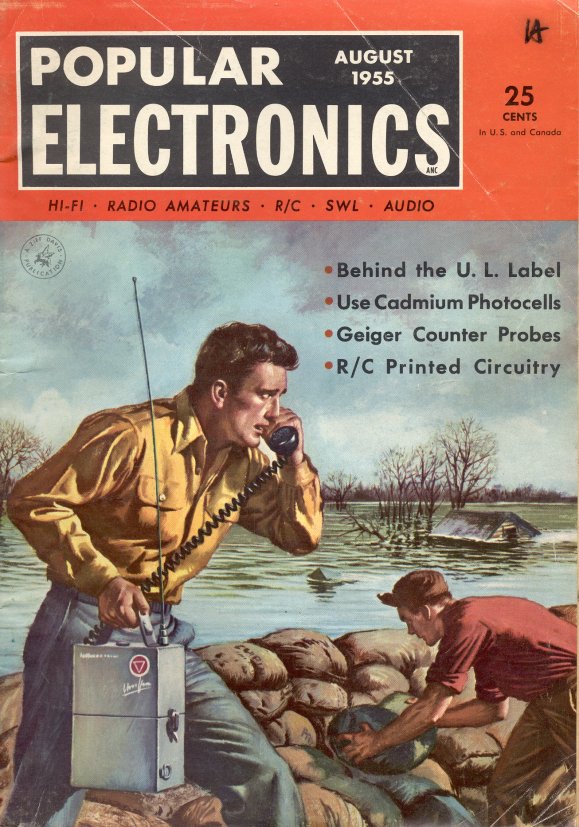

The covers are thus well-preserved, and remarkable. For the first

year and change of PE's existence, its covers were water-color paintings.

Some were better than others, and the best of them capture scenes

that would be difficult to photograph on demand. Consider, for example,

the drama of the August 1955 cover below:

A square-jawed hero and his life-saving Civil Defense 2-way radio—talk

about the late-night fantasies of young solder-scorched nerds! Less

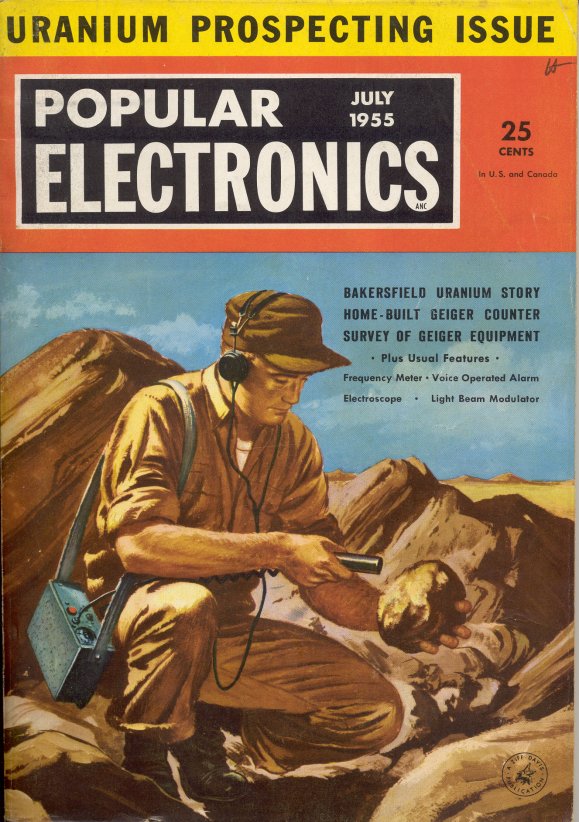

dramatic but no less indicative of the 50's zeitgeist was

the July 1955 issue, which was largely devoted to the uranium prospecting

craze of that era. Build your own Geiger counter, go out into the

still-empty West, and let the riches of the atom announce its presence

into your 2000-ohm headphones:

(By the way, I'm sure that there's a name for that style of cap.

What is it? Can I get one? I already have the headphones.)

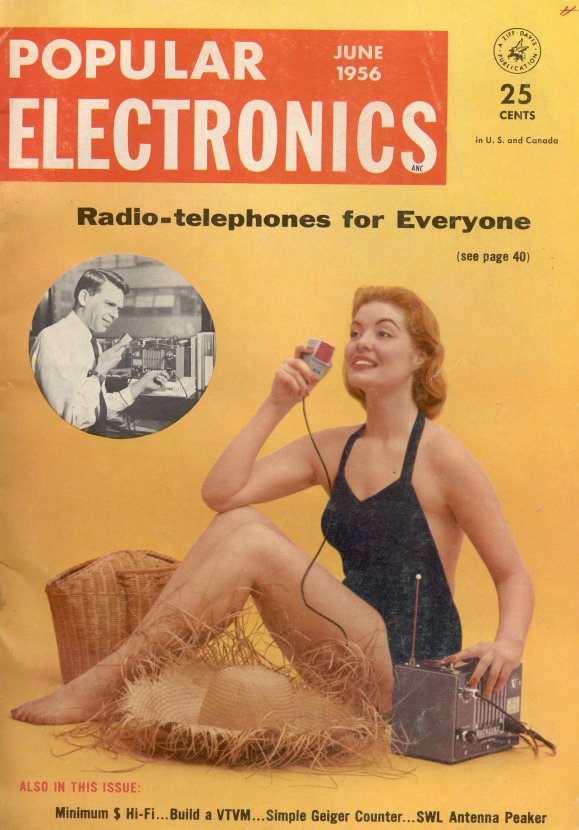

The watercolors went away in early 1956—my guess is that the

artist started demanding a bigger cut—and the covers became

photographic. Gadgetry and women, often in extremely unlikely juxtapositions,

soon dominated the design. This must be what some calculating New

York art director figured would bring in the maximal nerd audience:

Gosh! Radio-telephones for everyone—even redheads! (The article

on p. 40 was actually a single page about the new Class B 465 MC

Citizens Band, and the redhead was nowhere in sight.)

Skimming the mags themselves has been a lot of fun, and it's interesting

to see that the nerd passions abroad in 1956 are still with us:

Radio-controlled planes and robots, communications of all kinds,

audio equipment, and even computers, though more as objects of awe

("Gigantic electronic brains!") than something to be tinkered

together in the basement. I hope to do another entry here on some

of the ads in the mid-50s mags. The Knight Kit Space Spanner! CK768

RF transistors! "You can make more money with an FCC license!"

American Beauty Electric Soldering Irons!

No, I wouldn't want to go back there, but damn, some of that stuff

calls to me!

|

October

18, 2006: My Personal Security Program October

18, 2006: My Personal Security Program

Several people wrote (of yesterday's entry) to ask that if I disapprove

of Symantec's security solutions, what do I recommend? And what

do I use myself?

First of all, it's not entirely about software, and certainly not

about one product. One package from one vendor can never be the

solution to everything. What I do is fairly simple, and I have little

or no problem with malware. Here's what I recommend, because here's

what I do, in decreasing order of importance:

- Be behind a router. They're cheap, and extremely strong

protection from unsolicited outside connections from script malware,

which studies have shown scan your IP address every few seconds.

Even if you only have one PC in the house, get a router. They

contain a Network Address Translation firewall, and most allow

you to block specific ports. The one I use is the Linksys 8-port

router/switch, model BEFSR81.

- Don't use IE. Just don't. Almost anything is safer. I

have it installed because the occasional nitwit Web site won't

render correctly without it, but IE often goes untouched for months

on end. Use either Mozilla

Firefox (which is free) or Opera,

which has also been free for about a year now, and is superb.

- Make sure "install on demand" is turned off in

your browser. Certainly, if you run IE at all, this is desperately

necessary.

- Don't use either "big" Outlook or Outlook Express

for email. These are malware magnets largely because they're

so popular, but they also have some fundamental problems that

make them spam facilitators. (They also use IE to render HTML-formatted

email, which makes them vulnerable to most of the same exploits

that plague IE.) I used Poco Mail for a long time, but recently

abandoned it for corrupting my mailbase. I use Mozilla

Thunderbird now, and am quite happy with it, even though Poco

has a few nice features that I miss on occasion.

- Don't surf to porn, warez, or obscure music sites, especially

those that offer deals that seem too good to be true. These are

the primary source of browser exploit trojans.

- Research every piece of "free" software you install,

thoroughly—and resist installing stuff on impulse. This

especially includes browser toolbars and ridiculous crap like

those heavily advertized smileys, which are highly malevolent

spyware and have gotten some of my nontechnical friends into a

world of trouble. If you must fool with such stuff, buy a copy

of VMWare Workstation 5 and learn how to use virtual machines

(VMs) as software testbeds. I test everything I download in a

VM before I ever think of installing it directly on the hardware.

Stuff that I end up not using much I just leave in a VM image

on my very big hard drive.

- If you must surf to dicey sites, do so from a browser operating

in a VM. I go to ebook pirate sites regularly watching for

pirated Paraglyph material, and when I do so, I pinch off a new

image of a standard VM and then revert it to the stored image

when I'm done, whether it looks like I was attacked or not.

- Use a low-profile virus checker like AVG. I have used

AVG Free for some

time now, having also tried Panda and found it too resource-hungry.

Viruses are less of an issue than they used to be, especially

if you're not so stupid as to open any email attachment that rides

in the door, or install warez downloaded from P2P networks.

- Use a two-way software firewall. I use Zone

Alarm and have some some years now. It allows me to control

what actually gets out to the Internet, and it lets me know when

any app even tries to connect. Much modern software, even if it's

completely legitimate, wants to "phone home" for reasons

never entirely explained. ZoneAlarm puts an end to that. Also,

if you contract some kind of spyware or trojan, ZoneAlarm will

let you know when the bad stuff tries to make an outside connection.

That's what I do. Interestingly, I don't do something that makes

a lot of sense, and I really should try it: Run Windows as something

other than admin. If you create and work from within a limited-permissions

account, malware based on exploits (or anything else, for that matter)

cannot install itself. You have to reboot into admin to install

software, but how often do you actually install software? If you're

configuring Windows for a non-technical person who is primarily

interested in Web and email, and perhaps word processing, this is

a very good thing to do. Unfortunately, some software doesn't work

correctly in limited user accounts, and you may not know which software

fails until you try it.

Finally, before all my Mac friends start yelling, you can buy a

Mac. Macs are largely immune to malware because the machines are

fairly rare and sparsely connected (compared to Windows) and malware

authors are looking for raw numbers. However, if Apple would ever

get its head out of its own you-know-what and decide to become a

major player, the bad guys could turn their attention to OS/X. I

have not yet been convinced that Mac software is somehow inherently

exploit-free—and I think complacency would be a very

bad thing.

So there you have it. Note that a lot of my list cooks down to, "Don't

be an idiot." It isn't all about software. It's about common

sense and a little caution. The best trainable, configurable anti-malware

system is you.

|

October

17, 2006: Battling Symantec October

17, 2006: Battling Symantec

I wonder sometimes what poor Peter Norton thinks of the software

that now carries his name. I just got back from spending over two

hours with a friend, picking fragments of Norton Antivirus out of

his machine with a tweezers. I met Peter a couple of times in the

1980s, and he was a completely pleasant guy, if kind of quiet. I

used his stuff for a lot of years. I certainly won't use it again,

and it has nothing to do with him.

What used to be Norton products are now owned by Symantec. There

are two problems with Symantec's security products. (I have no experience

with their other stuff.) To wit:

- The security stuff is so feature-bloated that it will reduce

even the fastest machine to a crawl.

- It is virtually impossible to uninstall in the conventional

manner, by way of a Windows uninstaller.

Symantec makes the case that our malware situation is so bad that

a really comprehensive security solution can't help but slow a PC

down. There is some truth in that, if you feel you have the right

to go anywhere online and click on anything you see without consequences,

especially if you're running IE. A relatively simple strategy, like

being behind a router, turning off browser install-on-demand, not

opening arbitrary email attachments, and resisting the urge to visit

porn sites will get you 80% of the way there without making your

system run like a PII-450.

Uninstallation problems are less excusable. Forget the conventional

uninstaller. It just doesn't work. To get rid of Symantec security

products you have to download the Norton Removal Tool from Symantec's

site and run that—but as I found earlier today, that's no guarantee.

When I ran NRT on Dean's machine, it got a certain ways along before

telling me that WinFax Pro was installed, and I had to uninstall

that first before running NRT. NRT then aborted.

One problem with that: Nowhere that I could see on that system

was any least trace of WinFax Pro, and Dean had no memory of ever

seeing or using it in the past. That left me the hard way: descending

into the Registry to nuke hundreds of Symantec keys, manually disabling

seven or eight Symantec autostart services, and deleting hundreds

of megabytes of Symantec files. When we were done, the machine ran

again like the 2.4 GHz P4 it was born to be. Degunking R Us.

Symantec gets away with this because its stuff is preinstalled

on virtually any new machine you can buy over the counter right

now, and most people will just pony up the money after the 90 day

"trial" (in several senses of the word, heh) than try

to pry the thing's ugly little claws out of their systems. Not me,

boy. The first thing I do with any new machine is whatever it takes

to get every last stain of Symantec off the hard drive. However,

since I will probably have to assemble my own machines from now

on to avoid the Vista tax, I will avoid the Symantec Disease as

well.

Do it if you can. The cure is almost as bad as the disease.

|

October

16, 2006: Just-In-Time Bookstores October

16, 2006: Just-In-Time Bookstores

Chris Gerrib

posted a link today to an

article in the (London) Sunday Times, about what might

happen to bookstores if we can ever get the cost of one-at-a-time

book manufacturing down to something that competes with conventional

book printing and binding.

It's worth reading, if you bear in mind that the author of the

piece doesn't completely understand the problem. Much of the disruption

in retail bookselling is due to massive discounting by online retailers

like Amazon, which forces B&M (bricks'n'mortar) bookstores to

meet discounts, at least on popular books. B&M bookstores in

turn force some of their infrastructure costs back on publishers

by charging for preferred positioning of books. And squeezed publishers

then force some of those costs back to authors by cutting advances

and royalty rates. (Authors are still looking for somebody to force

those costs back to.)

My own opinion is that publishing as an industry still has immense

overcapacity from the 90s, triggering a race to the bottom led by

large publishers that need to keep staff and facilities busy. Publishing

would be well served if about half of publishers went out of business,

heh. You first, Alphonse...

Closer to the heart of the problem is the inability to predict

sell-through of any given title. That was in fact the topic of a

longish article by Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg on the front page of

today's Wall Street Journal. (I don't think the piece is

online anywhere but the WSJ paid site.) Publisher Henry Holt

& Co. took a bath on what they considered a "sure thing,"

a novel called The Interpretation of Murder. They paid $800,000

for the book (a first novel by an unknown writer) and printed 185,000

copies. Even though early reviewers loved the book, the public did

not. We won't know for awhile how many of those 185,000 copies will

ultimately have to be pulped, but my guess is, well, most of them.

There are other damaging problems afflicting publishing, primarily

the concentration of control in a mere handful of people at two

massive retail chains, but the question of capital tied up in roll-the-dice

books that may never sell is probably worse. (That is what ultimately

put Coriolis Group Books out of business in 2002.) The Times

article linked to above suggests that bookstores as we know them

will ultimately be replaced by small storefronts at which purchasers

can order basically any book, which is immediately printed and bound

by a machine in the back room, with a click-to-clunk time of only

minutes. People (myself included) have been predicting that for

seven or eight years, ever since the Docutech-class

of book manufacturing machines hit the streets. Close...but not

quite.

Book manufacturing will eventually move to the same premises as

book retailing, but with a twist: Books will still sit on shelves

for browsing, and purchasers will still roam the aisles, picking

out books and carrying them to the checkout counter. The difference

is that all of those books were printed in the basement, and as

soon as one is sold, the monster book-o-matic downstairs will queue

up another one. Front-line staff will constantly grab books from

the book-o-matic's output bin and run them upstairs, where they

will be re-shelved at the places from which purchased copies were

taken. Currently popular books (think John Grisham or Harry Potter)

will be printed in tens or twenties rather than ones or twos, but

the stock depth will be dictated by an algorithm that monitors sales

over time. Obscure titles may not be reprinted and restocked immediately

after their shelf copies are purchased, and huge numbers of older

and marginally viable titles will not be printed at all until they

are actually ordered. The news there is still good: Grab a cup of

coffee and in five minutes (depending on machine traffic) The

Secret Tofu Recipes of 33rd Order Masons will be handed to you

by a beaming young store staffer.

This is not print-on-demand so much as just-in-time manufacturing,

and while it will not eliminate wasted paper copies completely,

it could cut waste and returns from thousands or tens of thousands

of printed copies to something south of a hundred, which is a capital

hit any publisher can absorb. We would still have bookstore aisles

to meet attractive people in, with books to browse and serendipity

around every corner. Publishers will still waste money promoting

bad books, but the money wasted will be less. With less wagered

on every roll of the dice, publishers may be willing to broaden

the base of their frontlists and take more chances on more people.

The long tail would get longer and perhaps even fatter, since no

book would ever really become unavailable.

I think economics will force book publishing and retailing to a model

something like this, but the technical challenges of putting that

kind of machinery in every bookstore (and keeping it running!) shouldn't

be underestimated. Think fifteen years, not five—and the sooner

the better!

|

October

15, 2006: Nunsuch October

15, 2006: Nunsuch

Pete

Albrecht send me a picture of a toy he found in what's left of the

American Science Center

catalog, from a place on the northwest side of Chicago where I spent

most of my discretionary cash that didn't go for books when I was

a teen. The toy is a rubber-band powered gun that shoots little

plastic nun figures. It's called (cringe) a "Nunchuck." Pete

Albrecht send me a picture of a toy he found in what's left of the

American Science Center

catalog, from a place on the northwest side of Chicago where I spent

most of my discretionary cash that didn't go for books when I was

a teen. The toy is a rubber-band powered gun that shoots little

plastic nun figures. It's called (cringe) a "Nunchuck."

The device isn't remarkable; similar toys exist that throw plastic

pigs and plastic cats. What I find remarkable about the Nunchuck

(and many other nun-toys like boxing nun puppets and wind-up walking

plastic nuns that shoots sparks out of their mouths) is this: When

was the last time you actually saw a nun? Basically, how is

it that young people (under 30 or so) even know what a nun looks

like these days?

Nuns were once a part of the American landscape. The big Marshall

Field's department store in downtown Chicago (now gutted to irrelevance

as a Federated) used to have a separate ladies' room for nuns. I

saw the (locked) door reading "Nuns' Lounge" myself on

a higher floor, and wondered as a young child what a lounging nun

would look like. Everybody remembers Sally Fields' 1970s TV series

"The Flying Nun," and "perky nuns" got their

own entry (unfairly, I think) in The

Encyclopedia of Bad Taste, right after "Pepper mills,

huge."

Nuns vanished from the American scene to a great extent by the

early 1980s; I think they were gone from my grade school before

that. Many smaller orders of religious sisters have vanished completely,

and the larger orders are now mostly reduced to elderly nuns caring

for extremely elderly nuns. The sisters who remain do not wear the

elaborate habits that our culture remembers; in fact, their dress

is often simple and plain enough to be mistaken for that of a soccer

mom.

What we may be seeing here is the visible manifestation of a more

subtle truth: Nuns were a force to be reckoned with. They

were the people who made Triumphalist Catholicism happen, down on

the street and in the classrooms, by the pure force of their wills

and personalities. Many were very lonely, unhappy women, and that's

where the bad press comes from. Not everybody can be a runway model

or a firefighter, and not everyone can be a nun. But the women who

were born to the manner and stuck with it throughout their lives

were genuine heroes.

And I think nuns have stuck to our cultural consciousness because

of that heroism, not because of the psychological problems that

some had. My own Sr. Maristella (my oldest cousin, now in her 70s)

is one of the kindest and most soft-spoken people I've ever met,

and although there were some whacko nuns in my own grade school,

most of the nuns I had managed classrooms containing 48 or even

50 rowdy kids with an equilibrium (and in some cases a sense of

humor) that no one appreciated at the time.

We remember nuns because they are now mythic creatures, much like

steam trains, which built America with the same impressive mythic

power. Nuns had (and still have) a grip on our imaginations. Heroism

and true power do that in a way that deviousness does not. (Quick:

Show me a toy that tosses little plastic senators!)

|

October

13, 2006: Odd Lots October

13, 2006: Odd Lots

- One very useful application of Flash lies in posting schematic

diagrams. I took the Visio schematic of my 6T9 tube stereo amplifier,

exported it from Visio as a .AI file, imported the AI file into

Flash, and then exported the diagram as a .SWF file. The SWF is

only 22KB in size, which is much smaller than a TIF of

similar resolution would be and comes down in a fraction of the

time. Take

a look. It prints well from Firefox, with the sole glitch

that the art does not appear in the print preview screen.

- I pass this

along only because Herman's Hermits' "No Milk Today"

is one of my all-time favorite pop songs—and for the sake

of an animated bouncing udder. As silly as anything I've seen

in some time. Maybe a very long time.

- Jim Strickland sent me a pointer to this,

which I would perhaps consider even sillier if it didn't border

on "too true to be funny" territory.

- Make sure you get one

of these before your next all-geek cocktail party.

- I take a certain amount of heat for building and flying kites.

How immature, heh. But

lo! I may be getting my revenge. (How soon before this gets

into Popular Mechanics?)

|

October

12, 2006: Resurrecting a Computer Book on Lulu October

12, 2006: Resurrecting a Computer Book on Lulu

Back in 2001, Julian Bucknall published The

Tomes of Delphi: Algorithms and Data Structures with Wordware

Publishing, and it became something of a legend. The book's been

out of print for awhile, and used copies are selling on Amazon Marketplace

for $200 and up. Whoa.

There's definitely a message in that market. With rights now reverted

and in-hand, Julian has republished the book on his own through

Lulu.com. You can now

order that $200 book for $25. Wordware sent me a review copy

when it first came out in 2001 (alas, too late to review in Visual

Developer Magazine) though it disappeared somewhere along

the way. I just ordered a new copy, but my memory of the book is

still solid: If you do anything in Delphi beyond stringing components

together with one-line event handlers, this book needs to be on

your shelf.

That would be good enough news right there, but Julian's gone further:

He's written a three-part article on how he went about re-creating

and re-publishing the book, which stands as the best single description

of the print-on-demand publishing process that I've yet seen. Part

1. Part

2. Part

3.

If you have any least interest in print-on-demand publishing, read

them closely and in order. A number of lessons emerge from his experience:

- Publishing at book length is now possible for almost anyone.

It's still a lot of work, but there are no real gatekeepers, as

there are in conventional publishing. You don't have to persuade

anyone to list or carry your book. You follow the process, and

it's published.

- There is very little real money in print-on-demand (POD) publishing.

This has been true since the dawn of POD time. What is said less

often is that there is very little real money in conventional

publishing anymore, either.

- The real strength in POD publishing is re-publishing out-of-print

books to capture "long tail" demand. Julian's book is

exceptional in that regard, in that the book had an unusually

good reputation in its first life, rather like Michael Abrash's

Graphics Programming Black Book, a 1,340-page behemoth that

we published at Coriolis in 1997. Used copies were selling in

the $80 range until relatively recently.

- But that said, POD publishing is extremely length-sensitive.

Unit manufacturing cost is 2c per page plus $4.55. Julian's book

is 524 pages long, so its UMC is $15.03. That's over twice (and

approaching three times) what it would cost to print each copy

in 4,000 copy quantities using a conventional offset press. Michael's

book would have a UMC of $26. Ouch.

Julian tells us that he has sold 110 copies in one week.

That's little short of astonishing, though some of that is probably

an initial blip of pent-up demand. Books like this are less version-sensitive

than most computer books, so there's a good chance that the book

will sell steadily for years to come. And one overwhelming advantage

of Lulu-style self-publishing is that the author does not have to

warehouse books, process orders and payments, dun deadbeat retailers,

or handle the inevitable bookstore returns.

Julian speculates (and I agree) that POD books should go for depth,

not breadth. It might be better for all parties if POD books were

shorter (100-200 pages) and priced at about $20-$25. (I think that

Julian underpriced his book by $5-$8 and consider it a honking bargain.)

Based on his experience, I am considering taking my book Degunking

Your Email, Spam, and Viruses and breaking it up into three

separate books along the obvious topic lines, updating them, and

publishing them on Lulu. I don't expect his kind of success with

it, but the book reviewed well enough for me to think that it still

has some value.

My efforts to publish on Lulu were stymied for months by a weird routing

problem that I recently solved (see my entry for September

20, 2006) and it's time to get back on the task. More here as

it happens.

|

October

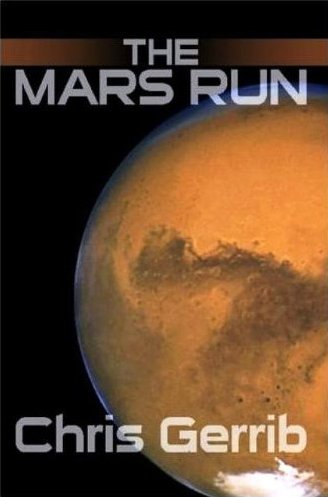

11, 2006: Review: The Mars Run October

11, 2006: Review: The Mars Run

William

Langewiesche's cover story for the September 2003 Atlantic

("Anarchy at

Sea") was a riveting description of high-seas piracy as

it happens now. None of this "arrrrr, matey" stuff.

It's about multiply nested shell corporations, illusory ship registrations,

an utter lack of law enforcement on the high seas, and (especially)

assault rifles. Although I've read of "space pirates"

in cheap novels for forty years, all of them have leaned toward

the kind of nitwit romanticism that has ultimately given us Pirates

of the Caribbean and a lot of funny hats. William

Langewiesche's cover story for the September 2003 Atlantic

("Anarchy at

Sea") was a riveting description of high-seas piracy as

it happens now. None of this "arrrrr, matey" stuff.

It's about multiply nested shell corporations, illusory ship registrations,

an utter lack of law enforcement on the high seas, and (especially)

assault rifles. Although I've read of "space pirates"

in cheap novels for forty years, all of them have leaned toward

the kind of nitwit romanticism that has ultimately given us Pirates

of the Caribbean and a lot of funny hats.

Not this one.

Chris Gerrib's first

novel is about space piracy in a near future (the 2070s) in

which commerce among Earth, Mars, and certain asteroids has become

routine. The story is told from the point of view of a 19-year-old

girl whose disfunctional family cannot help her with conventional

college tuition, so she enlists in a sort of space merchant marine

academy and becomes a bottom-rung astronaut. On her first run to

Mars her merchant ship is attacked by pirates, and she is given

a choice: Join us as a pirate, or die on the spot. She joins, intending

to escape as soon as possible, and travels on to Mars and back to

Earth, where she spends some time in the pathetic Central African

Empire (a real country of sorts, albeit one where the emperor had

the bad habit of eating his subjects) which is creating a spit-and-baling-wire

space navy specifically to prey on spacecraft from developed nations,

including the US. Janet eventually triumphs, but it's a difficult,

degrading road, which sees several abortive escape attempts and

some time spent as a sex slave of the son of the pirate ringleader.

This is a first novel, and for a first novel (I've read more than

a few) it works quite well. Chris is a Navy man and has spent considerable

time on shipboard, so his descriptions of the nuts'n'bolts of long-haul

space travel ring very true. He also has an intuitive grasp of the

criminal mind, and we get a clear picture of the pirates as reckless,

clumsy opportunists who succeed by a small measure of skill and

a great deal of luck—which eventually (as with all criminal

luck) runs out.

The great flaw of the book is actually a shortcoming of the medium:

We have a size eight novel built on a size six frame. The story

sucked me in and moved me along, but there was a bare-bones feeling

about it, and I kept wanting more of the background of the future

that he's painting here. Janet Pilgrim's character development was

present and adequate, but I felt that, given her circumstances,

I would have liked to know more about the woman she rapidly becomes

once she leaves the Earth. Even with her as the viewpoint character,

a great deal happens "off stage."

After talking about it with Chris, the explanation was clear, and

something entirely new in SF publishing: The constraints of the

print-on-demand publishing medium. The Mars Run was published

through Lulu.com, where the unit manufacturing cost (UMC) is directly

proportional to the page count. Chris calculated the length of the

novel that would allow him to make money while keeping the cover

price in line with conventionally published trade paperback SF,

and he wrote to that length. As I discovered while writing The

Cunning Blood, a given story wants to be told at a given length:

What I had hoped would be a 90,000 word novel turned out to be 145,000

words instead. Chris found the discipline to keep the word count

down, but at the cost of the story's backdrop fading into a necessary

indistinctness.

That's really a vote of confidence from me. The action was straight-line

and almost continuous, once we got past a slightly slow beginning.

I would gladly have read it at twice the length. There's only one

caution: Although the protagonist is only 19, the story has some

very violent moments and there is a fair bit of explicit sex, so

it is not something you should hand to young readers.

And one other interesting note: Lulu sells the book both in printed

form and as a PDF-based ebook. I bought both, and read the novel

twice, once in each medium. (I read the PDF on my Thinkpad X41 tablet

while shivering in the corner of our unheated RV on our peculiar,

blizzard-haunted

"late summer" camping trip up in the mountains.) The

DRM-free PDF sells for only $2.68, and you get it Right Now. (Shipping

time for the print edition is perhaps a day or two slower than what

you'd see with Amazon.) I was interested in seeing how good Lulu's

order fulfillment is, and was very happy with the results.

187 pages. Paperback

$10.96. Ebook $2.68. ISBN 978-1-4116-9973-1.

It's about the future, in more ways than one. Recommended.

|

October

8, 2006: Finally, Bev Bivens on CD October

8, 2006: Finally, Bev Bivens on CD

A

very long time ago, I bought the first We Five album (on vinyl—this

was 1966) and dropped it on the basement floor, taking a huge chunk

off the edge. I had played it maybe twice; if my parents had been

home at the time, they might have heard a few brand new words out

of me, right up through the floor. Somehow I couldn't bear to buy

it again, especially with so much to choose from and so little money

to actualize my choice. And I never thought to look for it again

until a few weeks ago, and was delighted to find that the first

two albums from We Five are now available on a single CD. A

very long time ago, I bought the first We Five album (on vinyl—this

was 1966) and dropped it on the basement floor, taking a huge chunk

off the edge. I had played it maybe twice; if my parents had been

home at the time, they might have heard a few brand new words out

of me, right up through the floor. Somehow I couldn't bear to buy

it again, especially with so much to choose from and so little money

to actualize my choice. And I never thought to look for it again

until a few weeks ago, and was delighted to find that the first

two albums from We Five are now available on a single CD.

Most of you have probably never heard of We Five, and at most you

may have heard their sole hit, "You Were On My Mind" on

the oldies stations or in K-Mart. The group was in fact a musical

framework for one of the most amazing female voices to come out

of the 1960s: Beverly Bivens. (Not to be confused with 70s artist

Beverly Bremers. Please.) In my estimation, only Karen Carpenter

ever topped her for smoothness, purity of tone, and vocal emotion.

There is excellent vocal harmony here, especially in "Softly,

as I Leave You," but without Bev, there wouldn't be much to

comment about.

We Five was odd among 60s groups for a number of reasons, perhaps

the most significant of which is that they didn't try to write their

own music to pad out their albums, but preferred to do quirky covers

of Broadway show tunes, like "I Got Plenty of Nuthin,"

"Tonight," "My Favorite Things," "Softly

as I Leave You," and "Small World, Isn't It?" as

well as covers of pop songs made famous by others, like "Cast

Your Fate to the Wind." This makes the disc completely listenable,

something that isn't always the case with albums. There are a few

loser cuts, but I almost found myself hearing them with a pang of

nostalgia. Some of the arrangements do not work well, particularly

"I Can't Help Falling In Love With You, which is too fast (and

has a little too much Spanish guitar) to do justice to the lyrics.

But overall, it's a fine collection, and Bev Bivens can certainly

make a song work that would simply sink without her amazing voice.

You may have to be an Almost Old Person like me to love it like I

do, but hell, that's what blogs are for. Highly recommended.

|

October

7, 2006: How We Used to Grow the SF Market October

7, 2006: How We Used to Grow the SF Market

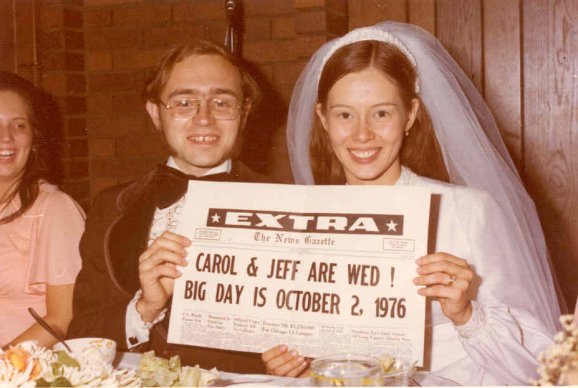

Back

when Carol and I were in Chicago this summer, cleaning out her mom's

house, we found a lot of old books, some of which had been in the

basement for a long time and (quite apart from their yellowing and

brittleness) just smelled. One was a 50c mass-market paperback murder

mystery from 1961, and although the book fed the dumpster, it had

a couple of familiar bind-in postcards promoting the Science Fiction

Book Club. Back

when Carol and I were in Chicago this summer, cleaning out her mom's

house, we found a lot of old books, some of which had been in the

basement for a long time and (quite apart from their yellowing and

brittleness) just smelled. One was a 50c mass-market paperback murder

mystery from 1961, and although the book fed the dumpster, it had

a couple of familiar bind-in postcards promoting the Science Fiction

Book Club.

Like most people, I subscribed to the SFBC for some years in the

70s, and it had an interesting effect on me: I read stuff I wouldn't

have chosen on my own. Some of the lousier titles in that group

are long gone, but two of the better ones that I still have are

The Winter of the World by Poul Anderson and The End of

the Dreams by James Gunn. I don't much like heroic fantasy,

and I find cover paintings of impossibly endowed women in brass

bras a little off-putting, but Anderson's story sucked me in and

I felt that I had gotten my money's worth. I think Gunn's book was

the first of his that I ever read, and I liked it enough to hunt

down the rest of his material.

So

the SFBC was a brilliant concept: Push stuff at people, having given

them limited but not absolute choice, and you will broaden their

tastes, and thereby broaden your market. The fact that they placed

their postcards in books without any least relation to SF (like

murder mysteries; who knows where else they went?) was something

that wasn't clear to me at the time, but it's just the next highest

level of the same concept: Get people curious about what they haven't

seen yet. It helped that reading was a popular pastime back then;

a lot of people bought stuff "just to have something to read"

and weren't especially picky about what it was. Give them limited

choice ("choose any three!") and they'll feel like they

had a hand in the decision, while the real choice is made back at

the central office. So

the SFBC was a brilliant concept: Push stuff at people, having given

them limited but not absolute choice, and you will broaden their

tastes, and thereby broaden your market. The fact that they placed

their postcards in books without any least relation to SF (like

murder mysteries; who knows where else they went?) was something

that wasn't clear to me at the time, but it's just the next highest

level of the same concept: Get people curious about what they haven't

seen yet. It helped that reading was a popular pastime back then;

a lot of people bought stuff "just to have something to read"

and weren't especially picky about what it was. Give them limited

choice ("choose any three!") and they'll feel like they

had a hand in the decision, while the real choice is made back at

the central office.

Today, with Amazon allowing us razor-sharp choice in our reading,

we tend to narrow our tastes until we start complaining, "Ten

million books and nothing on!" It makes sense to read outside

your core tastes, but nothing compels us to do that anymore. And no

matter how much we may say we value recommendations calculated to

our precise tastes (in wine, books, music, and anything else of an

aesthetic nature) there is something delightful about stumbling across

something you enjoyed but would never have chosen on your own. That

was what the SFBC was about, and I wonder if there's any future in

such a "surprise me!" mechanism in our heavily networked

age.

|

October

6, 2006: What I Mean When I Say "Flash" October

6, 2006: What I Mean When I Say "Flash"

If I learned anything in the wake of yesterday's entry, it's that

different people are touching entirely different parts of the elephant

when they talk about Adobe's Flash. For most people, Flash is still

the animated movie-maker that it's been since the very late 1990s.

(And people really really hate Flash splash screens!) But

non-artist that I am, that's not the aspect of Flash that interests

me.

What I see when I think "Flash" is a mechanism for coding

up and deploying RIAs (Rich Internet Applications) that (preferably)

contain no animation at all. The platform that Adobe created for

doing this with Flash is called Flex. The

Flex platform is conceptually similar to AJAX, but seems way

less haywire to me.

Flex consists of three major elements:

- ActionScript 3.0, which is an object-oriented scripting language

superset of ECMAScript.

- MXML, which is an XML-derived markup language for defining UIs

and data bindings.

- The Flex Class Library contains components including controls,

data containers, and data protocol managers.

A Flex compiler compiles all three of these elements into a binary

file with the extension .SWF. The SWF file is loaded and run by

the Flash Player (almost always a browser plug-in) which contains

a bytecode virtual machine and a JIT compiler. The jitter compiles

the SWF to native code as needed. When you've got a finished and

debugged SWF, you publish it to a Web host where people can request

it via HTTP and execute it via their Flash Player browser plug-in.

As with most compiled languages, you can write source code files

in any old text editor and then compile them to SWF with the free

command-line compiler that Adobe makes available. But I was delighted

to see that Adobe has implemented a Flex IDE using Eclipse. The

product is called Flex

Builder, and I just installed the trial version this afternoon

to take a look. The Eclipse implementation is very good, and even

has a Delphi-like drag-and-drop palette for Flex components. The

Adobe site has some nice tutorials, and I was able to create a (trivial)

app in twenty minutes, allocating abundant time to poke at the IDE

and understand what it was I was actually doing. The $750 price

of Flex Builder is a little daunting, but I will admit, it's very

slick.

So that's what I really mean when I say "Flash": a genuine

programming platform where the focus is code and not eye candy. I

suspect I should cut the confusion by calling it "Flex."

As the Star Child said, I'm not entirely sure what to do with it yet—but

I'll think of something.

|

October

5, 2006: Odd Lots October

5, 2006: Odd Lots

- Mitch Kapor is redeeming himself from the embarrassment of his

silly look'n'feel litigation days by mounting (and apparently

funding) a very promising Open Source replacement for Microsoft

Outlook called Chandler.

I'm not sure it's quite complete enough to spend much time with

(and sheesh, Mitch! You've been at it for three years now!) but

I'm watching it closely. I've tried a lot of similar software,

but have yet to find anything I could really throw my weight behind.

This could be the one. We'll see.

- I ordered a computer table today from Unfinished Furniture Warehouse,

on Stone St. in Colorado Springs. It's basically a hack of a standard

trestle-based small dining table, in alder wood. They're taking

down the vertical members so that the table surface is 26 1/4"

above the floor, and cutting the table depth from 40" down

to 32". The table length of 72" will be unchanged. For

the stain they're going to match a shelf I took in from one of

my bookshelves here. They have a number of finished pieces on

hand as examples of their work, and I am mightily impressed.

- I'm studying the Flash platform, and it strikes me that Flash

is hugely better than HTML for anything but the simplest

of static Web pages. In fact, Flash is amazingly like Java and

.NET, which must be one of the best-kept secrets of the Web programming

world. What I knew of Flash came mostly from books that Coriolis

published on it circa 2000, which were targeted at graphics designers

and seriously shorted the programming side of the platform.

- Cripes. I'll bet the German police are killing each other to

get put on this

case.

|

October

3, 2006: My New Chair October

3, 2006: My New Chair

Back in the summer of 1988, when we were still living in Scotts

Valley, Carol and I went up to San Francisco just to walk around,

and we happened into the Just Chairs office furniture store on Bryant

Street. I sat in a few chairs, and somehow one just felt absolutely,

unutterably right. I bought it on the spot, even though the

damned thing cost me $1200, which was more than we had ever spent

for any single item of furniture in our 12 years of marriage.