|

|

|

|

April

30, 2006: Detecting LightScribe April

30, 2006: Detecting LightScribe

The optical drive on my 1.7 GHz Xeon croaked a few months ago,

and I only just now bestirred myself to order a new one. (I'd been

coasting on a 1997-era CD-only slot drive pulled from the junk pile

since then.) The new drive is a Samsung

SH-S162L, which intrigued me because it supports LightScribe.

LightScribe is a new technology

that allows you to flip an optical blank over after you burn it,

and etch a label onto the top (non-data) face using the same laser

that burns data onto the back. The blanks are special in that they

have a burnable layer of foil on the top face, without the usual

manufacturer printing.

The drive puzzled me because it didn't come with a custom driver—and

remarkably enough, that's SOP in the optical drive world. Samsung

does not post a driver for its optical drives on their support site.

Nonetheless, it works. Win2K identified it as an optical drive,

and installed the standard 1999-era optical drive driver. Nero understands

all of its data-related functions (even those that didn't exist

in 1999) and I've successfully tested all of its reading and writing

modes. The one thing that I can't get it to do is execute the LightScribe

functionality. Neither the OEM version of Nero that came with the

drive nor MicroVision's

latest SureThing CD Labeler (which claims LightScribe support)

detect the drive as having the LightScribe technology.

So without a custom driver, how the hell does anybody know that it's

a LightScribe drive? I've sent an email to MicroVision asking about

this (Registry key? TSR? Black magic?) but if any of you have had

any experience in this area, I'd appreciate a short note.

|

April

29, 2006: What the Hell Are Publishers For, Anyway? April

29, 2006: What the Hell Are Publishers For, Anyway?

Here we go again: A major NY publishing house got its head handed

to it, for publishing a novel written by a 17-year-old high school

girl who innocently (we hope) cribbed heavily from at least one

of her major competitors, and perhaps others. The author is Kaavya

Viswanathan, daughter of two Indian immigrant physicians. The book

is How

Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life, a teen-angst

YA potboiler about a studious girl who was refused entrance to Harvard

because she didn't have a social life. The publisher is Little,

Brown, a major house that has been around since the Flood and ought

to know better. Go to Amazon, find the reviews, scroll past the

schadenfreude tsunami, and see what people who hadn't heard about

the scandal had to say about the book: "It reads like a mish-mash

of every bad teen cliche and movie out there." And she got

half a million dollars for doing it.

I won't scold Kaavya here. The best thing that could happen to

her would be to get kicked out of Harvard, a school that specializes

in giving its students the impression that they're receiving an

education. Assuming that she actually has some writing talent, her

literary career is not over. She simply has to go to a state school

somewhere, actually learn something, and wait for the heat to die

down.

The story interests me because it's yet another illustration of

dysfunctional publishing. Little, Brown bought the book from a packager,

17th Street Productions, which grinds out indistinguishable YA novels

using a stable of nameless word technicians who can follow an outline

and receive a flat fee—but no royalties or byline—for

producing a novel to template in six weeks flat. They didn't invent

this mechanism. As best I know, that honor falls to the

Stratemeyer Syndicate, a book factory founded in 1905 and responsible

for household words like Nancy Drew, the Bobbsey Twins, and Tom

Swift. Series packagers are everywhere. When I was in college I

was asked by a local packager if I could write porn novels from

outlines in six weeks, for a flat fee of $1800. (Major money

for a college kid in 1974!) I tried—but hey, they always say

to write about what you know. Kaavya came to the attention of 17th

Street Productions through IvyWise, a big-ticket college entrance

consultancy hired by her parents to get her into Harvard. In a stunning

piece of thermonuclear networking, the staff counselor at IvyWise

found Kaavya an agent and got 17th Street interested in a deal.

The real problem is this: A publishing house that can afford to

pay a high school student half a million bucks for a lousy book

should be able to afford front-line editors who know the genre and

have developed feelers for plagiarism. This is a related problem

to the one (famously tripped upon by Doubleday in the A Million

Little Pieces affair) facing publishers of memoir, where somebody

had better ask: Did this stuff really happen at all? Memoir

is a species of mutant journalism, but still one that requires a

certain level of fact checking, especially for truly outrageous

statements.

It makes one ask: What do the big, rich NY publishers actually

do? Little, Brown didn't go looking for the book. It was

handed to them on a platter. They clearly didn't do much development

on it, or it might have read a little better. They poured it into

print, they handed it to the bookstores, and they made a fortune.

I'm a struggling publisher who knows a lot of struggling publishers.

We're scraping by, struggling to get decent books into bookstores,

and barely making any money at all. Something's very wrong with

this picture, but it's far from clear what could possibly make any

of it better.

On the other hand, part of me has to cheer a little for the kid. I

wrote three SF novels in high school, one of which (in my sophomore

year) broke 200,000 words, hammered out entirely on my grandmother's

rickety Underwood Standard typewriter. I was doing it for fun, and

while I knowingly cribbed from a lot of things from Tolkien to Star

Trek, I had an intuition that it was a sort of training, and never

gave much thought to publication. Some of the cribbing was in fact

unintentional: In my junior year I built a rather silly novel around

the idea of a cubical planet, not knowing (until my friends at our

Lane Tech lunch table told me) that what I had described was the Bizarro

World, from the Superman comics. (I was not allowed comic books as

a kid and had read only a handful in high school.) I do confess to

some envy at her early success; after all, it took me 35 years after

writing A Question of Flatness to get The Cunning Blood

written, polished, and into print. What was lacking in 1968, and still

seems to be lacking, is some mechanism for spotting high school kids

with genuine writing talent and offering them some sort of adjunct

education to give them some confidence and accelerate their grip on

their field. I had absolutely no formal training in writing (apart

from high school essays) until I went to the Clarion SF workshop in

1973, and once I knew how it was really done, I got myself published

in a matter of months. One could imagine similar workshops for technical

writing, for newspaper articles, for romances or any other genre with

commercial potential. It smells like a low-grade entrpreneurial opportunity

to me, and if enough scandals like Kaavya Viswanathan's cross my desk,

I might seriously think about pursuing it.

|

April

27, 2006: Sympathy on the Loss of One of Your Legs April

27, 2006: Sympathy on the Loss of One of Your Legs

I've been staring at a story on my screen for the past hour or

so, reading it over and over and trying to decide what, if anything,

still needs to be tweaked. I'm stumped—and that means it's

ready to be reformatted for submission, and packed off to Analog.

It's the first brand new short story I've written since the fall

of 2000, just before things started to get nuts in my life. (Coriolis

imploding, moving to Colorado, etc.)

Some years back, I was in a greeting card shop looking for a card

for some occasion or another, and in scanning the rows of cards

I happened upon one that appeared (at first look) to have a very

odd message on its front face: "Sympathy on the Loss of One

of Your Legs." Damn, there really is a card for every occasion!

On second look, alas, it was not so. The card really read, 'Sympathy

on the Loss of Your Loved One."

Silly it might have been, but as mistakes go it was a keeper, and

I filed it away for future use. It took a few years, but eventually

a story spun itself around that unlikely card concept. It's short,

light, and should make you smile. Let's see how long it takes to

get it into print.

I have another story in revision that I hope to turn loose within

the next couple of weeks. Assuming I do, it will be the first time

that I've had two stories out on the street chasing markets at the

same time in close to twenty years. Writing a story every four or

five years is no way to make a reputation. I need to pick up the pace

a little. Or more than a little. Way more.

|

April

26, 2006: Sturgeon's Sweetness April

26, 2006: Sturgeon's Sweetness

We

had one of our little writers' workshops here at my house on Saturday

afternoon, and George Ott submitted his best story yet—one

that, with some polishing, will almost certainly be his professional

debut piece. I won't say much about the story itself, beyond the

fact that it was about a pair of unusual people working in obscurity

for the good of humanity, while trying very hard to keep

their efforts under wraps. We

had one of our little writers' workshops here at my house on Saturday

afternoon, and George Ott submitted his best story yet—one

that, with some polishing, will almost certainly be his professional

debut piece. I won't say much about the story itself, beyond the

fact that it was about a pair of unusual people working in obscurity

for the good of humanity, while trying very hard to keep

their efforts under wraps.

After I had read the story, one of the first things that occurred

to me is that it reminded me of Theodore

"Ted" Sturgeon (left) who taught at my Clarion in

the summer of 1973, when I was barely 21 and away from home absent

my parents for literally the first time. (I was slow to sieze the

perks of adulthood.) There were other very big names at the workshop

that year (Harlan Ellison, Ben Bova, Kate and Damon Knight) but

Ted was different. Harlan was a talented blowhard, Bova had

very little emotional flavor at all, Damon was rather hard-bitten,

and Kate so blindingly brilliant that she terrified me. (She did

a private Tarot reading for me, an offer that I found so intimidating

that I have absolutely no recall of what she said.) Ted Sturgeon,

on the other hand, had a sort of gentle, self-effacing brilliance

that I had never seen before and have not seen since. I had always

liked his fiction without quite understanding why, but during his

week as teacher it became obvious, as I studied a couple of his

stories and wrote a story of my own in imitation of his style.

I consider "Marlowe" one of my best published stories,

though almost no one's ever read it. My one and only royalty report

indicated that the hardcover anthology Alien Encounters had

sold...125 copies. So it goes. It was my first big break from hardware-oriented

fiction, and the first time I had tried to put some emotional nuance

into a tale. The first pass was a mess (though I knew I was on to

something when the artsyfartsy faction at the workshop dumped on

it with vicious intensity) but I cleaned it up and sold it anyway,

and part of that I credit to Ted Sturgeon's quiet encouragement.

It's yet another "absense of father" story (I write those

a lot) in which a strange disembodied intelligence adopts the guise

of an abused young girl's deceased father to teach her to fight

back against the neighborhood toughs in a chillingly effective way.

One of the things that Ted Sturgeon taught was to appeal to as

many senses as possible. Too much fiction relates only sight and

sound. There are smells and tastes and textures in the world too,

and careful use of them in descriptions can add an additional dimension

to a tale. He also developed the technique of falling into blank

verse to change the mood in a story without necessarily alerting

the reader, and tried to teach it to us. Some of the workshop knuckleheads

ended up inserting rhymed couplets in their stories, to hilarious

effect. (Few seemed to understand the "blank" in "blank

verse.") I tried it in "Marlowe" and I think it worked,

because no one has ever spotted the passage.

Howerver, Sturgeon's trademark as a writer of SF is a kind of disarming

intimacy that stood out like a kleig light against the psychotic

sexual paranoia of the 1950s and early 1960s. There was a warmth,

a sweetness in many of his tales that I saw nowhere else

in the SF world. Sturgeon utterly lacked cynicism. Utterly.

Quite the opposite: There was an undercurrent of hope and goodness

beneath his best stories that still brings tears to my eyes.

Ted Sturgeon died in 1985. I don't hear people talk much about

him anymore, and while his stories are all still in print, I wonder

if people still read him. If you haven't read him yet and are looking

for something different, three come to mind that I consider his

best:

- "Make Room for Me." Three talented individuals achieve

a sort of higher intelligence in response to a small-scale and

unseen alien invasion. The bond they share is not explicitly sexual,

but still deeply intimate in a way that implies the sort of closeness

that sexual unity facilitates. I'll never forget the tag line

at the end: "What Vaughan inspires, I design, and Manuel

builds." It's the humblest way I ever heard anyone say, "We

work miracles."

- More Than Human. This is one of Sturgeon's few full-sized

novels and probably his best known piece. Five variously wounded

and weirdly talented children and a mentally handicapped man create

a group mind that transcends the human weakness that invariably

leads to evil. In doing so, they redeem a psychopathic killer,

and almost casually invent antigravity to help an old farmer get

his truck out of a muddy field. The novel includes a vicious attack

on racism from an era when segregation was still legal (1953)

and reads well today, fifty-odd years on.

- My very favorite Sturgeon, of course, will always be "The

[Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff," a longish novella about

two affable aliens who perform a sort of laboratory test on a

group of human beings living in a boarding house. This is one

of those stories that affects me differently as I grow older.

When I was a teen, the suicidal obsessions of Phil Halvorsen were

completely incomprehensible to me. Now, in my 50s, I understand

depression, and Phil came alive for me on my last reading as he

never did before. This is perhaps the sweetest of all the major

Sturgeon stories, and some who've been infected by cynicism (our

most insidious disease) call it corny. Don't be fooled. It's as

good as SF gets.

It's been a few years for me, so I'm going to pull down all his books

and go through them again, from one end to the other. I've had a tough

six or seven years, and I need a booster shot against cynicism, and

inspiration to write some new material about love, hope, and triumph.

I'll let you know if it works, but Sturgeon can do it if anybody can.

|

April

25, 2006: The Wines of Colorado April

25, 2006: The Wines of Colorado

This

past Friday night, Carol and I and our friends David and Terry went

up Highway 24 through Ute Pass, and stopped for dinner at The

Wines of Colorado, in Cascade. It's a slightly unusual combination

of wine shop and restaurant, with the twist that every single wine

they sell is made right here in Colorado. This

past Friday night, Carol and I and our friends David and Terry went

up Highway 24 through Ute Pass, and stopped for dinner at The

Wines of Colorado, in Cascade. It's a slightly unusual combination

of wine shop and restaurant, with the twist that every single wine

they sell is made right here in Colorado.

The restaurant is informal, with seating both inside in mountain

lodge decor and outside on the banks of a small creek. (It was mighty

chilly at 9,000 feet Friday night, so we ate inside.) The food is

not fancy, but it was superb: I had a half-pound buffalo burger,

Carol had an Austrian bratwurst (I guess they don't make them in

Colorado), Terry had a steak sandwich, and David had a chicken caesar

salad. All entrees were under $10. I'm partial to buffalo meat,

and this was one of the best burgers I've ever had, irrespective

of species. They didn't grill the mushrooms to mush, and even the

roll was home-baked and tasty, if a little crumbly around the edges.

The best part of Wines of Colorado (which some might call a gimmick)

is this: After you order your food, you go down the hall to the

wine shop, where the tasting bar is located. They have twenty bottles

of wine open for tasting, arranged in a semicircle from dry (on

the left) to dessert sweet (on the right.) You can try as many as

you want, and then order a glass of any of them for $4.25. Considering

how often I've paid $6 or more for a glass of Sutter Home white

zin or some crappy cheap Chardonnay that turned my mouth inside

out, that's a steal.

I chose a late-harvest Zinfandel that surprised us all by not being

as sweet as most dessert wines, while having a wisp of effervesence.

(I've tasted the same thing a time or two with certain Gewurztraminers,

but you can't always count on it, even with the same vineyard, wine,

and vintage.) The subtle fizz took some of the edge off the sweetness,

and while I wouldn't have chosen it to accompany a rare steak, it

was fine burger accompaniment. The wine is from Balistreri,

and is unfined (unfiltered), which makes the fruit borderline explosive.

Not for everyone, but I've long been a Zinfandel fanatic (both dry

and sweet) and bought a couple of bottles to take home. $24.

Overall, it's a great place to stop for dinner if you're in the Pike's

Peak area. Just get

on Highway 24 and go uphill (west) to Pike's Peak Highway at Cascade.

Turn left and you're there; it's right off 24—and right on the

road to the top of Pike's Peak. Highly recommended.

|

April

24, 2006: Dr. Ebola April

24, 2006: Dr. Ebola

I hate to be so negative two entries in a row, but this one deserves

some discussion. Rich Rostrom sent me a pointer to

an article by Forrest Mims, the author of many popular electronics

books, who witnessed an almost unbelievable lecture by a progressive

biology professor at the University of Texas at Austin. In this

lecture (for which all recording was strictly forbidden) Dr. Eric

R. Pianka told his audience that at least 90% of all humanity had

to die for the good of the Earth. Furthermore, he described in detail

his favored mechanism: An airborne form of the Ebola virus.

Forrest Mims is dissed in many circles because he's a Christian,

and a lot of people assume that Mims exaggerated or made up the

whole thing to discredit Pianka. This doesn't appear to be true;

see this

article particularly.

Assuming Pianka said what he did (and apparently teaches perspectives

like that to undergrads) why did I have to read it on the Internet?

Where's the outrage in the press and on TV? There are only two possibilities

here:

- It's a hoax. This doesn't seem to be the case, but I readily

admit that it's possible.

- The media is embarrassed because this weasel is a member of

their tribe, and they're protecting him by omission—by not

saying anything at all about the case, essentially declaring that

it's "not news." The media did this before with Ted

Rall, the progressive cartoonist who called our Secretary of State

a nigger in one of his cartoons.

Keep in mind what this guy is saying: That somebody should hack

the Ebola virus—one of the most deadly viruses ever discovered—from

a pathogen that requires blood-to-blood contact to something that

can float on the air and be inhaled, and then turn it loose. Like

all charismatic individuals, he has worshipful followers who agree

with him and, if the opportunity presented itself, could get down

to business and begin hacking the virus. Doing this stuff will only

get easier over time. The very worst of it is that Texas taxpayers—and

to some extent, Federal taxpayers, whose money ends up as grants

at a great many colleges—are paying this guy to encourage bioterrorism.

It is to boggle.

|

April

22, 2006: Rant: The Enemies of the Earth April

22, 2006: Rant: The Enemies of the Earth

Perhaps the most single most depressing thing in our current political

scene is the way that obstructionists (many of whom know nothing

at all about environmental science, nor care) have hijacked the

environmental movement. Even setting aside nuclear power for the

moment (it's actually our greatest hope for defusing the global

warming threat) it boggles the mind how ferociously some self-styled

"environmentalists" battle solar, wind, and hydroelectric

power projects, no matter where they're located. Some of this is

nimbyism hiding under the mantle of concern for the environment;

the mansion trash class will reliably rise in indignation to "save

the birds" from wind turbines any time someone wants to build

one within driving distance, when the selfish fools are really thinking

about nothing but proppity valyooz.

Other folks say, "We don't need to build more power plants.

We just need to use less power." Perhaps they don't understand

that we've been making huge advances in efficiency in all of our

technology for thirty years and more, but with rapidly rising populations

(especially in India and China) we're simply treading water, all

the while dumping a steady stream of CO2 into the atmosphere. What

some of these people are secretly wishing for is that three quarters

of humanity would simply drop dead, so that they and their tribe

could treat the Earth more gently. If there is a more damaging fantasy

infecting the collective unconscious, I've yet to spot it.

None of this is original. You've seen it many times. Nonetheless,

my point for this Earth Day is worth restating: The obstructionist

faction of the environmental movement is destroying the Earth, by

preventing any useful action on global warming. We need to be building

tens of thousands of wind turbines, and dozens of new nuclear power

plants, and we need to be doing it right now. If you actively

oppose the building of non-carbon energy sources, I'll be blunt: You're

helping to destroy the Earth. Do meditate on that, and Have a Nice

Day.

|

April

21, 2006: Con*Tact Paperbacks April

21, 2006: Con*Tact Paperbacks

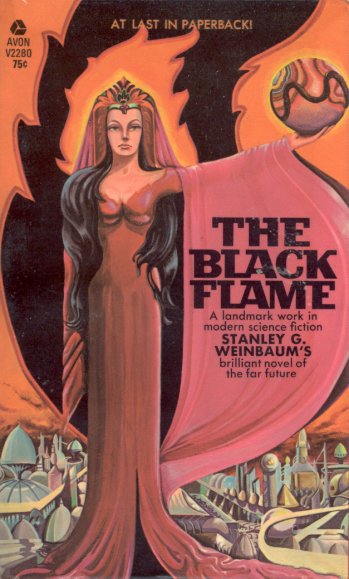

Reader

Carrington Dixon wrote to tell me that he had caught my reference

in The Cunning Blood to Stanley G. Weinbaum's novel The

Black Flame, and prompted me to go downstairs and dig out the

book, which I doubt I've seen (except briefly, to throw it in a

box when moving) for thirty years. My copy is the Avon mass-market

paperback from early 1969. Although the story itself was good, what

I had found arresting as a teen was the cover art. I've always liked

intelligent and strong-willed women, and the image of Margot of

Urbs made my blood pound a little. Reader

Carrington Dixon wrote to tell me that he had caught my reference

in The Cunning Blood to Stanley G. Weinbaum's novel The

Black Flame, and prompted me to go downstairs and dig out the

book, which I doubt I've seen (except briefly, to throw it in a

box when moving) for thirty years. My copy is the Avon mass-market

paperback from early 1969. Although the story itself was good, what

I had found arresting as a teen was the cover art. I've always liked

intelligent and strong-willed women, and the image of Margot of

Urbs made my blood pound a little.

The book has survived beautifully across 37 years for a simple

reason: When I brought it home for the store (and before I allowed

myself to even open it) I covered it with transparent Con*Tact adhesive

plastic sheeting, with which my mother often used as shelf paper.

The adhesive was strong, and over a period of a year or so melted

right into the carboard cover, creating a smooth matte finish and

protecting the printed image from creases.

Between 1966 (when I first got an allowance) and about 1975, I

covered all my paperbacks in Con*Tact transparent plastic. So I

have a middling collection of SF paperbacks downstairs in which

the pulp pages are brittle and crumbling, but the cover art looks

as good as it did when I brought it home from Kroch's & Brentano's.

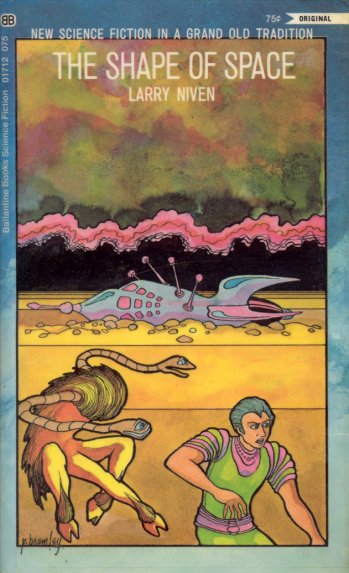

Maybe

it's just the nostalgia effect, but I think that SF cover art in the

1967-1975 period reached a kind of peak. (That may also map to its

explosion in popularity as Boomers like me started to have discretionary

cash.) The Doc Smith series, William Tenn's collected works, and Heinlein's

stories and novels all appeared about that time, with distinctive

artwork unlike anything you'll see today. One of my favorites is the

cover to the 1969 Larry Niven collection The Shape of Space,

drawn by the late Peter Bramley, who worked at National Lampoon

for awhile, and later did underground comics including Vinny Shinblind

(the Invisible Sex Maniac) and Prophet & Loss. The cover is peculiar

because whereas it's clearly a scene from Ringworld, the stories

inside have nothing to do with the Ringworld, Louis Wu, or the Puppeteers.

I'm wondering if Bramley was approached to do a cover for Ringworld,

and Ballantine found his art a little less cosmic than the novel seemed

to require. Doesn't matter; it's a great cover, and I wish that we

could get away from some of the cheeseburgercake (i.e.cheesecake and

beefcake art in one frame) and back to the genuine artistic imagination

of SF's Platinum Age. Maybe

it's just the nostalgia effect, but I think that SF cover art in the

1967-1975 period reached a kind of peak. (That may also map to its

explosion in popularity as Boomers like me started to have discretionary

cash.) The Doc Smith series, William Tenn's collected works, and Heinlein's

stories and novels all appeared about that time, with distinctive

artwork unlike anything you'll see today. One of my favorites is the

cover to the 1969 Larry Niven collection The Shape of Space,

drawn by the late Peter Bramley, who worked at National Lampoon

for awhile, and later did underground comics including Vinny Shinblind

(the Invisible Sex Maniac) and Prophet & Loss. The cover is peculiar

because whereas it's clearly a scene from Ringworld, the stories

inside have nothing to do with the Ringworld, Louis Wu, or the Puppeteers.

I'm wondering if Bramley was approached to do a cover for Ringworld,

and Ballantine found his art a little less cosmic than the novel seemed

to require. Doesn't matter; it's a great cover, and I wish that we

could get away from some of the cheeseburgercake (i.e.cheesecake and

beefcake art in one frame) and back to the genuine artistic imagination

of SF's Platinum Age.

|

April

20, 2006: Reactions to Readerware April

20, 2006: Reactions to Readerware

As time allows, I've been scanning and entering books and audio

CDs into the Readerware

book cataloging program. (See my entry for April

13, 2006.) In just a few hours I've gotten 752 books into the

system. Although computer books are probably my biggest single category

(I haven't cataloged several other major categories yet, including

SF/fantasy and science) all 351 books in that category got slurped

onto disk in only a little more than an hour. The key is that all

but two of my computer books had ISBNs, and probably 85% of them

had barcodes. Also, there's a certain knack to swiping a book with

the CueCat that develops over time. Having chewed through two other

categories before tackling computer books, well, I by then had the

arm and was spending at most two or three seconds per book.

The program has a lot of interesting features that I'm just getting

familiar with. It can export a catalog listing in HTML; here's my

biography category. You can choose and order the columns any

way you want. It's not fancy HTML, and it can be edited very easily.

It may take me another few weeks to get everything in. I'm guessing

that I have about 1800 books right now, having shed over a thousand

before leaving Arizona. A lot of my SF predates ISBNs, much less barcodes,

and not all of the mass-market paperback editions are necessarily

on Amazon. I still have quite a bit of work to do. Up next: Science.

|

April

19, 2006: Are We Short of Engineers? April

19, 2006: Are We Short of Engineers?

This morning's Wall Street Journal carried a short opinion

piece by Robert J. Stevens, CEO of Lockheed Martin, complaining

how the US is short of engineers and therefore falling behind the

rest of the world in technological innovation. His list of remedies

is all the usual: Spend more on education, bring in more foreign

engineers, work harder. The only thing he doesn't suggest is the

one thing no CEO will ever allow himself to say: Pay more for

engineering talent.

We are not short of engineers. I can say this with confidence because

if we were, engineering salaries would be going through the roof

(they're not), engineers would be the constant targets of headhunters

urging them to jump ship (they're not), there would be no unemployed

or underemployed engineers (there are many) and more students would

be entering engineering degree programs. (They're not.) Between

the lines I hear the constant mantra coming from everywhere in the

business world: We want employees who are young, childless, and

without significant medical problems, who are willing to work 80-hour

weeks for under $50,000 a year.

If we are indeed falling behind the rest of the world in technology

(and that's a highly debatable issue) the solution is not to generate

more engineers, but to do more engineering. And that will require

a whole raft of changes in the way business is done in the US:

- Our patent system is hugely corrupt, and is actively hindering

technological progress.

- Obstructionism under the guise of phony environmental concern

is holding back technology in many vital areas, especially energy

and transportation.

- Monopolistic powers held by telecommunications firms are holding

back what we can do with cell and wired Internet technology. Just

look at what they're doing in the Pacific Rim if you don't think

this is the case.

- Tort law is like molasses in the crankcase of every single area

of American endeavor. Employment lawsuits, environmental lawsuits,

product liability lawsuits are more and more disconnected from

reality and any reasonable concept of justice—companies can

be sued and destroyed for things they never did and over which

they have no control.

With all of that hanging over your head, engineering just isn't

much fun anymore. Nor does it pay especially well. Companies that

say, "Well, we can't afford to pay our engineering staff more

than we already do" always seem to find another $10 million

to throw at the CEO or other top exective staff. No wonder all the

bright young kids want to go into finance or management.

Everybody—CEOs in particular—must remember that labor is

a market. You can only offer so little for wages before you get no

takers due to the time and effort it takes to develop the skills required

to do the job. I think we're at that point in a number of fields,

primarily engineering and medical support. I have reflected that when

markets get efficient enough, they force prices down to the point

where nothing works especially well. Yet if you artificially raise

prices to the point where everything works well, large chunks of the

population can't afford the product. There's obviously a sweet spot

somewhere (there always is) but the kicker is figuring out how to

find it.

|

April

18, 2006: Go Local for Off-Dry Wine April

18, 2006: Go Local for Off-Dry Wine

Back

a few weeks ago when I was in Chicago, I went walking, and north

of Dempster along Waukegan Road I ducked into a small wine shop.

In browsing the aisles I found a wine I had never seen before: St.

Julian's Blue Heron White. It was cheap ($6.99) and the winery

name recalled my patron saint, Lady Julian of Norwich. Who could

resist that? Back

a few weeks ago when I was in Chicago, I went walking, and north

of Dempster along Waukegan Road I ducked into a small wine shop.

In browsing the aisles I found a wine I had never seen before: St.

Julian's Blue Heron White. It was cheap ($6.99) and the winery

name recalled my patron saint, Lady Julian of Norwich. Who could

resist that?

I had modest expectations, but the wine is actually pretty damned

good. It's somewhat sweeter than a white zin (4% residual sugar

vs. 2.5%) but with absolutely explosive fruit, and a distinct hint

of peach. The acid was modest, and kept the wine from trending sour.

Like most German whites, it's low in alchohol (9%) and very drinkable.

I would guess this would make a fantastic summer barbecue wine.

What's interesting about Blue Heron is where it's made: Paw Paw,

Michigan. The sticker isn't clear in the photo, but Blue Heron won

a gold medal at the 2003 Indiana State Fair. One doesn't think of

wines being made in Michigan, and one doesn't think of wine being

awarded ribbons at state fairs. Contrarian (and small-town boy at

heart) that I am, I consider those big pluses.

I can't find Blue Heron here in Colorado, and that doesn't surprise

me. There is a whole subterranean layer to American wine culture

under the category of local wines. And especially if you prefer

something not utterly dry (once you get past white zin, most nationally

distributed American wines have virtually no residual sugar at all)

local is the best place to look. There are many wineries in Colorado

(Cottonwood Cellars

is one of my favorites) that simply don't distribute out of state,

and many wineries in "odd" places (read here: anywhere

not on the West Coast) don't distribute beyond a few adjacent states.

Not all local wines are good. We had a bottle of a semi-sweet wine

from Indiana recently that was pretty bad (how it got into a Colorado

wine shop is unclear) and only about half of the Colorado wines

we have tried are worth mentioning. What local wines are is unpredictable,

and I mean that in a good way. Virtually all conventional Chardonnays

taste alike these days; for adventure you have to go to the vines

less traveled: Zinfandel, Pinot Noir, Niagara, Pinot Grigio, etc.

Stay away from Chardonnay and Cabernet. Popularity has ruined them.

And if you like a little residual sugar in your wine, find the local

wine corner in your local wine shop, and start reading labels. I've

found that local wineries are much more likely to list residual

sugar levels than national wineries, where the assumption is that

residual sugar on all wines is simply zero.

If you like semi-sweet wines and can find Blue Heron, grab it. St.

Julian's has another off-dry white called Simply White with 2.5% residual

sugar, which is a little less sweet. I'll try it next time I get to

Chicago and report back here.

|

April

17, 2006: Odd Lots April

17, 2006: Odd Lots

- San Francisco, that great haven of peace, love, and correct

thinking, is

by far and away the country's leading place for grab-and-run laptop

thefts, some of them including physical attacks. Laptops aren't

as compact as diamond necklaces, but then again, people aren't

commonly seen noshing on bagels at Panera in diamond necklaces.

Be careful—even if you're not in San Francisco. (If this

becomes a trend, plan on seeing more drive-by bandwidth "borrowing"

at unencrypted home routers, from inside the safety of a locked

car.)

- Egad. A

Difference Engine built in Lego. I stand amazed. Thanks to

George Ott for the pointer.

- Building real computers with toy construction sets is not original

to Lego. People have been making differential

analyzers with Meccano (the British antecedent to Gilbert's

Erector, and far superior in many ways) since the 1930s, not as

stunts but actually to do the math.

- And while we're talking Meccano, here is a photo of one of the

most complex Meccano models ever made: A

programmable crane, designed in the 1950s. The crane (called

"Robot Gargantua") obeys instructions punched into wide

paper tape, and can be made to stack blocks in arbitrary and very

precise patterns. The crude "low-res" nature of Meccano

parts reminds me of the molecular limitations of nanotech, and

when I see those molecular models of nanoscale mechanisms, I always

flash on the Meccano models of my youth.

- Having scanned my way through a few hundred books, and realizing

that I have lots more to go, I'm beginning to consider a

$250 wireless Bluetooth barcode scanner. Wretched excess,

I suppose, but it's easier to use than the CueCat and would allow

me to leave the computer in the middle of the room and carry the

scanner to the books and not vise-versa.

- Several people have asked for contact information for the photographer

who took the photo in my April 13, 2006 entry. On Location Photography

by Chazz, 5792 County Road 26, Longmont CO 80504. 720-494-4441.

720-494-4446 FAX.

- Pete Albrecht sent me a link to a Wikipedia entry on a

very peculiar internal combustion engine. I love engines,

the odder the better, and this is about as odd as they get. Give

the animation a chance to download fully, because without it you

don't stand much chance of figuring out how the damned thing works.

For more on engines, see Pete's April

16, 2006 Infobunker entry.

|

April

15, 2006: Jeff and Carol as of March 2006 April

15, 2006: Jeff and Carol as of March 2006

Readers

may remember that two days before we had scheduled a sitting with

a professional photographer, I

broke my damned glasses and had to scramble to get a new pair

of frames. Well, I got the frames the next day (serious luck!) and

today we received the photo prints themselves. Readers

may remember that two days before we had scheduled a sitting with

a professional photographer, I

broke my damned glasses and had to scramble to get a new pair

of frames. Well, I got the frames the next day (serious luck!) and

today we received the photo prints themselves.

We did a number of poses, separately and together, including a

conventional suit-and-tie publicity shot for me, but the one I like

best is at left.

The photographer was quite good, and his prices were much less than

a place like Glamour Shots, probably because he doesn't have to maintain

a retail presence in a mall. It was in part a fund raiser for our

church, in that the church charged us $35 for the sitting and then

we paid the photographer for the prints. As best we can tell, everybody's

completely happy, and the church made almost $600. The people we used

were out of Denver, but it's an interesting business model, and similar

firms may be at work elsewhere. Look around.

|

April

13, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 3 April

13, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 3

As my friend Roxanne Meida King commented on Contra's LiveJournal

mirror, there are disasters to fit every location. Watching The

Weather Channel certainly taught me that tornadoes range as widely

as the Norwegian rat, and I've long adhered to the maxim, Never

live near water. Then there's the ever-present hazard of neighbors

who smoke in bed, especially in urban areas where the bungalows

might be eight or ten feet apart. (When we lived on Campbell Avenue

in Chicago, we would awaken to the sound of the guy next door's

clock radio, even if both our bedroom windows were closed. He must

have been a hard sleeper.)

So homeowner's insurance is your friend, and we have always had

it. One challenge in making a claim is proving what you had, and

I'm adderssing that right now. Shortly after we moved in I went

around from room to room with our camcorder, making a Mini-DV tape

of the entire house. It's about time to break open another tape

and do it again.

Pondering losing the house here to fire prompted me to go back

to something I have thought about now and then for many years: A

database to record what books and audio CDs I have. I was thinking

about writing my own in Delphi and just never got excited enough

to do it. (Shortly afterward I began writing The Cunning Blood,

which I think was a better use of my time.) What I actually did

last week was purchase a three-utility bundle from Readerware.

They offer separate programs to manage books, audio CDs, and video

DVDs.

I had expected something kind of blah, but was pleasantly surprised.

The programs are very well designed, and I was astonished at how

quickly they've been devouring my books and media. The key is how

information is entered:

- If you have a barcode reader and the item has a barcode, scan

it.

- If there's no bar code on the item, type in its ISBN or other

unique ID code.

- If the item is pre-ISBN, look it up on Amazon, and drag the

item link to a drop target on the database program.

- If the item is so obscure that no major online service lists

it, type in everything manually.

Using those four techniques as required, you create a list of items,

and the list may contain as little as the unique product code. Then

you connect to the Net and turn the program loose. It goes up to

a pre-estabished list of online sites (which includes Amazon, B&N,

the Library of Congress, Amazon UK, the british Library, and many

others) and it gathers as much information on each item as it can

find, including cover or jacket shots where available. I've cataloged

211 books so far, and only a handful (I think 4) had to be entered

completely manually. I was amazed at how many ancient and obscure

books (like the 1870 Old Catholic manifesto The Pope and the

Council) are listed on Amazon. I found it, I dragged it to the

target, and the program took it from there. Sweet.

The disaster recovery benefits of having such a database are twofold:

First of all, they will indicate to the insurance company post-fire

that you're not telling a fish story and that you really did have

2,000 books. Second, when you go to rebuild your library, you have

a crisp record of what was there. I was surprised, in cataloging

the first 200 books, how often a smallish title came to hand and

prompted me to think, Damn, I forgot I had this!

The

barcode scan feature was a godsend. For the 75% of my books that

have barcodes, each book took maybe three or four seconds to process.

The hand scanner itself is our old friend the CueCat, which was

offered free if you bought the bundle of three programs. I'd heard

a lot about CueCat some years back, when it was condemned as the

tool of the Illuminati and the Siren singing to the Black Helicopters.

It's a cheap little thing with a photosensor in the nose of a stylized

plastic cat, and was manufactured by the millions by tech bubble

startup Digital Convergence. After the bubble popped the Cats were

remaindered and are everywhere, and you can get one for as little

as $3.50 on eBay. The

barcode scan feature was a godsend. For the 75% of my books that

have barcodes, each book took maybe three or four seconds to process.

The hand scanner itself is our old friend the CueCat, which was

offered free if you bought the bundle of three programs. I'd heard

a lot about CueCat some years back, when it was condemned as the

tool of the Illuminati and the Siren singing to the Black Helicopters.

It's a cheap little thing with a photosensor in the nose of a stylized

plastic cat, and was manufactured by the millions by tech bubble

startup Digital Convergence. After the bubble popped the Cats were

remaindered and are everywhere, and you can get one for as little

as $3.50 on eBay.

On some books, especially the grubby ones, it takes a couple of

swipes with the Cat to get the barcode, but the vast majority of

books clicked in three seconds or less. (Most of the time between

books was spent moving books from the "before" pile to

the "after" pile.)

I like the Readerware software and recommend it. Including the time

spent entering or searching for pre-barcode books, I found I could

do about a hundred books an hour. It'll take me a few weeks to get

it all in, but by the time fire season gets extreme here, we'll have

blown through the house and scanned it all. Then I can rest easy.

Easier. A little.

|

April

12, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 2 April

12, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 2

Abandoning your house to a wildfire is a little different from

abandoning a hard drive to a fatal malfunction. I have a shelf full

of software on CDs, and if a hard drive dies, I buy another one

and reinstall everything from CD. Abandoning the house to a fire

means that the CDs perish too, and although they're not impossible

to replace, some of the older products that I still use are difficult

to find because the vendors threaten online sites that sell legitimate

used install CDs.

I have backups of a couple of install CDs, and could conceivably

back them all up, but they're bulky, and even ripping ISOs requires

somewhere to store the ISOs. The high road is to make a physical

backup copy of each CD, pack them all in one or two CD wallets (I

would need space for thirty or thirty five) and then put them in

the safe deposit box. Saving them as ISOs on DVDs would save some

slots, but I still don't entirely trust DVD-ROM over the long haul.

Something in me keeps muttering, "smaller bits, shorter shelf

life."

But damn, we're low on space in our safe deposit box.

In addition to the installer CDs, I have a fair number of downloaded

install suites that are pure files and are not CD images. I already

back them up (though most can be freely downloaded) but the kicker

here is not the files themselves. Nearly all the commercial software

installers require an unlock code. I have a document that gathers

all the unlock codes into one place, but I've been careless about

keeping it current, and I now have a priority item on my disaster

plan for updating the unlock code file and making sure everything

is in it. There aren't so many that it'll be an especially big file,

and it can go on the backup media with all the rest of my workaday

files. I may also print it out (the keys will fit on one side of

one sheet, writ small) and tuck the sheet in one of the (many) pockets

in my briefcase.

It's not exaggerating to say that the value of the commercial software

that I've purchased far exceeds the value of the hardware that I

run it on. Only two of the desktop machines I have here are worth

anything at all (who pays real money for a Pentium 450 anymore?)

and together they might be worth $1500. I probably have $3500 to

$4000 worth of software on the shelf. This is something to think

about if you decide to create your own disaster plan. Hardware is

a commodity, and amazingly cheap. Software, by contrast, is startlingly

expensive, and if those CDs burn, they're gone.

All's peaceful on the mountainside here, but July 4 is coming,

and what the CSFD really worries about are kids setting the vegetation

on fire with bottle rockets. Every year they put out one or two

little fires caused precisely that way, and every year they worry

about one that they can't get to in time to control it. That is

definitely the stuff of local nightmares.

I guess I have some work to do.

|

April

11, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 1 April

11, 2006: Escape Strategies, Part 1

We watched a very serious desert wildfire from our roof in 1996,

when Carol and I lived in the wilder parts of far north Scottsdale.

It didn't come closer than five or six miles, but it scared me into

getting an SUV. If I ever saw a wall of fire like that coming at

us, I wanted a vehicle that would go through somebody's front yard

without effort or complaint.

I thought that fleeing Arizona would get us out of the path of

wildfires, but I was wrong. They happen here, and as my luck would

have it, a bad one is overdue, just like they're overdue for a bad

quake in San Francisco. (I mentioned this in my entry for April

7, 2006.) In the last few days, Carol and I have been pondering

what we would do if we heard on the news (or saw from our back deck!)

that a wildfire was heading our way. What indeed?

We've been thinking about what in this house is irreplaceable,

and what is Just More Stuff. The greatest part of what we own are

things we can always get again, if not precisely the same make and

model: Clothes, kitchen utensils, furniture, etc. I have a longstanding

collection of radio parts, but they are remarkably available even

today; if I need a 6T9 radio tube, well, I can get any reasonable

quantity for $5 each or less. I'd miss my two milk jugs full of

tube sockets, but I made myself admit that in the last twenty-five

years, I've used about fifteen of them, out of several hundred,

and there are countless tube sockets for sale on eBay.

The irreplaceables sort out into three major categories:

- Important papers.

- Computer data.

- Items of sentimental value.

We've been proactive about keeping important papers in our safe

deposit box, and Carol is considering which items of what we keep

here we would need to include in our "grab and run" scenario.

I'll return to this question in a future entry. She's researching

what we might need and why.

We already have data backups in our safe deposit box across town,

and update them monthly. I burn backup DVDs regularly and keep a

set in my briefcase. All my current work exists on five Cruzer Mini

thumb drives that live in the pencil groove of my Northgate keyboard.

My laptop lives in my briefcase. If we have to leave here in a terrible

hurry, I only have to scoop the thumb drives out of the pencil groove,

dump them in my briefcase, grab the handles, and run.

Items of sentimental value are the real issue. The bulk of what

we have in this category are photographs. I've scanned only a tiny

fraction of what we have, which lives either in cardboard boxes

or in about twenty five photo albums, which Carol has been keeping

since literally before she met me. These are a problem, because

of their bulk and their weight. I can move the loose photos and

slides into a couple of suitcases or Rubbermaid storage bins, but

the albums are big, many, and heavy.

As for "valuables," well, we really don't have any. Our

wall art is poster art, and Carol has never gone in for fancy jewelry.

My stamp collection includes the sorts of stamps that twelve-year-olds

cadge from relatives who work in offices. I sold off most of my

classic radios before we left Arizona, and apart from the big 1937

Zenith cathedral (and it's not going anywhere, sigh) I doubt I'd

get more than couple hundred bucks for everything I have left.

What we end up doing in response to a wildfire depends on how much

warning we have. Unless a fire starts very close to us, we'll have

at least an hour to pack and go, and (especially since I've been

in weight training) I can move a lot of stuff in an hour,

if properly motivated, heh. The 4Runner will hold all the albums

and a certain amount of other stuff. I'll throw in whatever I think

I can manage, and then we will run.

I love this house, and paid a certain amount of stomach lining

making it happen, but it's insured and I keep telling myself I could

walk away from it if I had to. It's got stucco walls and a concrete

tile roof, so it's about as fireproof as you can make a nice-looking

house these days. That gives it as good a chance as anything, but

a bad fire will take out almost anything except a cinder block bunker.

The trees in the area are highly combustible, and a stand of burning

scrub oak can light a house from radiant heat alone up to fifty

feet away, more in a bad wind.

Life is risk; what can I say? If we lose the house we'll go somewhere

else and build another one. With my Carol, my dog, and my briefcase

I can rebuild my life, and in a pinch I can do without my briefcase.

The key is being ready without being anxious, and that may be the

biggest trick of all.

More tomorrow.

|

April

9, 2006: The Gospel of Judas April

9, 2006: The Gospel of Judas

Several people have asked me in the last week or so what I thought

of the

Gospel of Judas, which is getting some serious publicity on

a

National Geographic special. I didn't know much about it, but

having read up on it a little I think the fuss is misplaced. A "gospel"

is simply a general word for an account of some events. The Christian

Bible has four gospels, which are the accepted accounts of the Life

of Christ. There are others; at least 20 are known from existing

manuscripts or else quotes or accounts in writings of Church fathers

like Irenaeus of Lyons. The Gospel of Judas is one of a group known

as the Gnostic Gospels, because they were written and held as sacred

by a Christian splinter group (or several groups) that we today

call the Gnostics. The Gnostics were a mystery tradition that attempted

to synthesize Christian teaching with non-Christian spiritual traditions,

many of them from Persia. Most of the Gnostic Gospels say pretty

much the same things, and Judas is no exception. If there's anything

explosive in the Gospel of Judas, I didn't spot it.

Like the other Gnostic Gospels, it drops hints of secret knowledge

that Jesus gave to the Apostles without making it generally known.

Here's a sample:

Jesus said, “[Come],

that I may teach you about [secrets] no person [has] ever seen.

For there exists a great and boundless realm, whose extent no

generation of angels has seen, [in which] there is [a] great invisible

[Spirit], which no eye of an angel has ever seen, no thought of

the heart has ever comprehended, and it was never called by any

name.

And that's the easy part. The rest makes my head spin. There are

lots of gaps due to the bad condition of the manuscript, which is

in a number of fragments that do not always represent full pages

of the codex.

It's important to remember that the Church assembled the Bible

from a large number of books circulating in the first centuries

after Christ's life on Earth. The New Testament was defined in its

modern form by Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria in 367, after a long

and sometimes stormy discussion among the learned men in the Christian

community. They drew a line around the books we now know as the

new Testament, and quite a few books were left outside the canon.

The Gospel of Judas is one of them. So although it may have some

historical significance (and it's good to preserve any ancient writings

we may come across) it won't change the Christian understanding

of Jesus, Judas, or anything else.

Elsewhere in the world of Jesus scamming, Richard Baigent (co-author

of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, from which The Da

Vinci Code was lifted pretty much verbatim) has a

new book coming out. He'd better, because he

lost his theft-of-content suit against Dan Brown, and has to

pay a fortune in court costs.

It's pretty clear where all the publishing money is going that isn't

going into SF or computer books, sigh.

|

April

8, 2006: Odd Lots April

8, 2006: Odd Lots

- I put a lot of work into my 10" Newtonian telescope, but

I'm an absolute piker next to a chap who spent

twenty years of his spare time building this 22" scope.

I am in awe, and if I were wearing a hat I would take it off.

Wow.

- I can't imagine that anybody with two hands and a restless imagintion

doesn't scan it regularly, but definitely put the Make

Blog on your shortcut bar. This is a blog devoted to interesting

(in any of several senses) "roll your own" technology,

courtesy O'Reilly's Make Magazine. My favorite on the current

scan (look quick before it scrolls off the bottom) is the bathtub-sized

Tomato Soup Battery. (So tomato soup is good for something besides

making me gag!) Engineering is by no means dead, nor does it lack

imagination.

- There were plenty of hoaxes floating around this April Fools'

Day, but I humbly submit this

as the best (or at least the most cerebral) of the ones I saw.

- I am nowhere near hip enough to live in San Francisco, but I

do think that the Frisco culture site Laughing

Squid deserves some sort of award for Best Logo. Also, scroll

down toward the bottom to see a map of the city implemented with

little multicolored Jello cubes.

- Pete Albrecht sent me a pointer to a

1945 Russell W. Porter illustration of one of the Japanese

fugo balloon firebombs that I mentioned in my April 7, 2006 entry.

Porter is legendary among telescope freaks for his finely-rendered

Art Deco drawings of telescope equipment, including the 200"

scope at Palomar. Drawing Japanese weapons was something of a

deparure for him, but his style is unmistakable.

- Finally, in one of the "Your Health" pages in a local

magazine, we found the little bit of wisdom below. I'm sure you

all remember when the air was 40% oxygen, right?

|

April

7, 2006: Wildfire and Fugos April

7, 2006: Wildfire and Fugos

Last night Carol and I went to a session put on by the Colorado

Springs Fire Department to warn homeowners about the dangers of

wildfires here where we live on the slopes of Cheyenne Mountain.

It wasn't an especially good session. The gloomy message from the

fire marshall cooked down to: We're going to burn badly at some

point, and everything you have is going to go up in smoke.

The last big fire in this area happened in 1950. We actually found

a couple of charred scrub oak trunks in the gully at the east edge

of our lot that clearly were the product of that fire. The

Hayman Fire of 2002 (Colorado's largest known wildfire) freaked

a lot of people out, and it sure sounded like they're just giving

up. Environmentalists have blocked most large-scale efforts locally

to clean out underbrush within the environmental easement areas,

and money for firefighting equipment, training, and personnel is

scarce because Colorado's state government (like all state governments)

prefers to spend its revenues on pressure groups with more influence

than local fire departments.

I'm not sure what's to be done. It may be the case that nothing

can be done apart from creating a strategy for escaping with Carol,

QBit, and my data backups. (I'll write more on such strategies in

upcoming entries.) We had a landscaping company clean out and trim

the vegetation in the gully, and that may be the end of what's possible

to protect our house.

Alas, the session reminded the SF writer in me of the Japanese

fugos (fire balloons) of WWII, which were designed specifically

to set the US on fire. (Two good fugo sites are here

and here.)

In 1944 the Japanese launched about 9,000 of them from the Japanese

mainland, of which a few hundred were actually found in the US,

one as far east as Michigan. They were not especially effective,

but that was to some extent a measure of our good luck: The WWII

years were especially wet ones in the western US. In fact, 1943

was one of only two years when the spillways on Hoover Dam had to

be used. (The other was 1974, a year when my mother's basement flooded

a number of times and parts of Loyola University were almost washed

into a swollen Lake Michigan.)

The Japanese Fugos were amazingly crude (the balloon envelopes

were made of paper) and it's not difficult to imagine a modern

fugo: Something the size and shape of a 2-liter soda bottle, with

a mylar envelope, helium canister, GPS receiver, microcontroller,

and a small incendiary bomb. A few hundred of those could do an

immense amount of damage (let's not imagine a swarm of thousands)

and if done carefully, no one would ever really be able to tell

where the fugos had come from. I guess such big, slow-moving things

as balloons could be shot down, but to me that's only modest comfort.

I've long since ceased to worry about ICBMs. The real threat these

days is anonymous warfare. The dangers of inexpensive cruise missiles

are something I've written about in the past, but sizing up Colorado's

wildfire hazards made me realize that you don't need nukes to nuke

a countryside. All you need is a balloon and an igniter.

|

April

6, 2006: Odd Lots April

6, 2006: Odd Lots

- More

evidence that lack of sleep may be (at least in part) responsible

for the modern plague of obesity and diabetes. Could this be one

cause of the "freshman

fifteen?" I put on zero weight when I went to

college, perhaps because my diet didn't change, but also perhaps

because I was in bed by 10:30 PM every night. (Thanks to Frank

Glover for the pointer.)

- In response to a number of questions over the years: As best

I know, I am in some way related to every Duntemann currently

living, and certainly to all that you may see on the Web. (Note

that this means "Duntemann" with two 'n's on the end.

There are many more one-n Duntemans, some of whom are relatives

as well.) John

Duntemann, Dr.

Thomas J. Duntemann, Matthew Duntemann, Mark T. Duntemann,

and Mary Ila Duntemann are my cousins. Their father John Phil

Duntemann is the last remaining person of my father's generation

to be born with the name. The Duntemanns living in Germany are

distant but still related. It's a rare name, which has allowed

me to draw the connections without a lot of dead ends. If I had

been born Jeff Johnson, well, I would have taken up another hobby

than genealogy.

- I used to have an ASCII chart framed on my wall, back when I

was doing a fair bit of assembly language. The chart's in a box

somewhere, and I don't need to know hex or decimal equivalents

of characters very often. When I do (which these days comes about

while I'm looking at URLs from spammers and phishers) I use this

page.

- Impact theories dominate catastrophism right now, but there's

another one with a good bit of drama and some reasonable science

behind it: flood

basalt eruptions. (Note: Very cool graphics!) Volcanoes

are incremental magma flows; in FBEs a large crack opens in the

crust and the crack just gushes lava in almost unimaginable quantities,

releasing massive amounts of gas in the process. Supposedly, every

known mass extinction in Earth's history maps to a major FBE.

The iridium-rich asteroid that whacked us at the end of the Cretaceous

could just have been a coincidence, or perhaps—and I haven't

seen anybody propose this yet—the stress it put on the crust

may have caused one or more FBEs.

|

April

4, 2006: Thinking of the Huddled Masses April

4, 2006: Thinking of the Huddled Masses

The recent immigration reform furor is the guldurndest thing. The

issue splits the body politic in some weird ways, which I think

further inflames the debate. Several of my progressive friends advocate

simply throwing the borders open and letting anybody who wants,

in any numbers at all, come here, stay, and work. These are the

same people who rant (rightly) about the lack of health care, about

the high cost of housing, about wages trending downward, and so

on.

They seem unable to connect the dots: Wide-open immigration

hurts the poor, and helps the rich. If you fancy yourself a

progressive, meditate on this a little.

The rich love illegal immigrants not only because they work cheap

(our native-born poor will do that as well) but because they

are absolutely docile workers. In particular, they don't go

looking for employment lawyers every time they get fired or even

find something in the workplace irritating. They'll do almost anything

to maintain a low profile. They do their jobs, they take their envelopes

of cash, and quietly go home.

There are only so many jobs at the bottom, and with illegals competing

with our native-born poor and working classes for what jobs there

are, lower-class Americans are the ones hurting the most. I've read

that quite a few bloodline Democrats among the working classes are

getting impatient with their party for not addressing illegal immigration,

and they could cross party lines this fall, as many did in 2004

over gay marriage. A recent survey summarized in the Wall Street

Journal showed both parties split on the issue, almost in the

middle: 42% of Democrats and 57% of Republicans want stronger border

controls without any amnesty program of any kind. It's the edges

versus the center: The center wants border enforcement beefed up,

and both fringes want amnesty and basically open borders. GWB favors

amnesty and thus is (in a sense) to the left of some Democrats on

this issue—now, how weird is that?

A line I hear a lot is that "immigrants built this country."

Yes, they did, my own grandparents and great-grandparents among

them. What might more correctly be said is that this country was

built on the backs and with the blood of immigrants, who lived in

miserable, crowded conditions, made very little money, and all too

often suffered terribly or died young from the hazards and sheer

exhaustion inherent in the work. Maybe unlimited immigration was

necessary in 1900—as I've written before, industrialization

had created huge labor shortages in the West between 1840

and 1970. It's certainly no longer necessary, and we have a tremendous

and growing labor suplus, one especially acute at the bottom, and

heartbreakingly acute among African-Americans, who are often the

ones displaced from bottom-rung urban jobs by illegals from Mexico.

As I said, it's a very weird issue, and weird issues can be dangerous

to political parties too tied to traditional positions. I'd like to

see us integrate and employ the huddled masses we already have before

letting in millions more.

|

April

3, 2006: The Difficulties of Fiction April

3, 2006: The Difficulties of Fiction

I got a long, thoughtful

review of The Cunning Blood on SFSite. It's not an unqualified

rave, and I'm fine with that, because the reviewer very precisely

fingered some of the weaknesses of the story: I didn't spend much

time showing how the Canadian-dominated 1Earth society worked, and

my characters are not especially deep. Characterization has always

been difficult for me, and I create a situation and plot first and

then devise characters to fit. Many writers first create a crew

of interesting people, and then invent something interesting for

them to do. I'm not sure that's better than what I do, but in truth

that's not how I work, and I think it results in a whole different

feel for novel-length works. As for 1Earth, well, if I can summon

the enthusiasm to write a sequel called The Molten Flesh,

people will see very clearly the ugly side of nanny-state Canada.

As for characters, several people have complained that Peter Novilio

is kind of dull and immature to be the novel's key player, but they

missed what I was shooting for: The Sangruse Device itself is the

main character. It's the character who changes the most in response

to the novel's events, but it was far from clear to me how to accurately

portray the creature's innermost thoughts.

I don't much like sequels that are just "more stuff"

happening after the end of the initial story. I'm a little tired

of Peter Novilio, and I suspect he will not appear in The Molten

Flesh, nor will Geyl, Nutmeg, or Filter Fitzgerald. My #1 priority

is to give a sense for a peculiar world in which the secret nanotech

societies are becoming more numerous and more powerful. Protea (the

society that Cy Aliotta was worried about) is the starring device,

and Cy was right: It makes Sangruse 9 look almost tame, but not

for any of the reasons you might suspect.

I have a lot of research to do before I can even begin it, on nanotech

as we understand it today (I wrote The Cunning Blood in 1998)

as well as space elevators, really large gas lasers, quicksand,

and a lot of other things. Creating interesting futures is not an

easy business, and doesn't happen quickly. I'm working as fast as

I can.

|

April

1, 2006: Gatheroo April

1, 2006: Gatheroo

I got a note from Mike Milkovich last week, telling me that he's

in the process of creating an alternative to Meetup. (He read my

March 14,

2006 entry.) His system is called Gatheroo,

and although I just got back from Chicago and haven't had a chance

to do much but the laundry, I think it's worth a look. At first

glance I like them a lot, especially since they're being sued by

Minnesota Public Radio for daring to use a made-up word with "gather"

in it. Those ever-so-righteous maroons over at MPR think they own

the word "gather." Will we ever put such thinking in its

grave? It's a ridiculous suit that will only make MPR look silly

and dry up donations—and if it goes any further, will generate

a fortune in free publicity for Gatheroo.

Mike's intent is to keep it a free system, and I'm going to join

and try to create a local Delphi group. I hope also to establish

a local group for Bichon Frise owners, and will suggest to Mike

that the system generate hand-out cards for groups. We walk QBit

and run into other Bichon owners in the neighborhood a lot, and

I'd like a card to dig out of my pocket and hand to them, directing

them to the Gatheroo group.

More later, but from what little I've seen so far I like it a lot.

|

|