|

|

|

|

July

31, 2005: 36 Years Without Being Rash July

31, 2005: 36 Years Without Being Rash

Carol

and I met 36 years ago today (see the story of our meeting in my

July

31, 2004 entry) and we had planned a low-key private celebration

with one another: a nice dinner at home, and the long-awaited ceremonial

opening of the bottle of Dornfelder Rotwein 1994 we have had in

the wine rack for ten years now. We were in Chicago last year and

could not open the bottle as planned, so this year will do. Who's

in a hurry? Part of the trick of creating a lasting relationship

is patience; patience with one another's peculiarities (of which

I had many in 1969) and patience with the way the relationship

evolves. Carol and I worked at getting along. If we seemed

to have made it look "easy," that's only because we're

relatively private people and don't air our difficulties in public. Carol

and I met 36 years ago today (see the story of our meeting in my

July

31, 2004 entry) and we had planned a low-key private celebration

with one another: a nice dinner at home, and the long-awaited ceremonial

opening of the bottle of Dornfelder Rotwein 1994 we have had in

the wine rack for ten years now. We were in Chicago last year and

could not open the bottle as planned, so this year will do. Who's

in a hurry? Part of the trick of creating a lasting relationship

is patience; patience with one another's peculiarities (of which

I had many in 1969) and patience with the way the relationship

evolves. Carol and I worked at getting along. If we seemed

to have made it look "easy," that's only because we're

relatively private people and don't air our difficulties in public.

Those difficulties are now mostly gone. The mills of patient love

(like those of God) grind slowly, but they grind exceedingly small.

Well. However small love grinds things, they don't always work

out as planned. Late Thursday afternoon, right before supper, Carol

and I were weeding the boulder terrace to the north of the house.

I pulled a thistle out by the roots, stumbled, and fell over backwards

into a patch of tall weeds at the bottom of our little hill. I banged

up my right arm a little on the bounder but was otherwise unhurt.

We went in, I dabbed some Bactine on the scrape spot on my arm,

and popped a couple of Aleves.

Friday

morning I noticed a red patch on my arm. It grew during the day,

as another formed on my left wrist, and a few more on top of my

head. By bedtime my arm looked like a war zone, with another rising

on the small of my back. My arm had started to itch viciously, as

did the other locations during the course of the night. Today the

itch got bad enough so that we canceled our romantic dinner at home,

and went to visit friends. The weeds had looked innocuous enough,

but just my luck to do a full bodyflop into a patch of poison ivy

camoflaged by tall grass. Friday

morning I noticed a red patch on my arm. It grew during the day,

as another formed on my left wrist, and a few more on top of my

head. By bedtime my arm looked like a war zone, with another rising

on the small of my back. My arm had started to itch viciously, as

did the other locations during the course of the night. Today the

itch got bad enough so that we canceled our romantic dinner at home,

and went to visit friends. The weeds had looked innocuous enough,

but just my luck to do a full bodyflop into a patch of poison ivy

camoflaged by tall grass.

So it goes. I suspect I'm going to have to go get myself looked at

tomorrow, as new spots are showing up on my face and legs and everywhere

else. Our romantic anniversary evening can wait until next July, as

can the 1994 Dornfelder. We've been together 36 years. Another year

won't hurt—even if it itches in spots.

|

July

30, 2005: It's a Planet! It's a Comet! It's Even More Planets! July

30, 2005: It's a Planet! It's a Comet! It's Even More Planets!

Oi

veh. It's raining new planets in here. Yesterday morning I first

heard about object 2003 EL61, a Trans-Neptuanian Object in our solar

system's Kupier Belt: the dustbin beyond the major planets where

debris from the creation of the Solar System gathers. It's big—perhaps

bigger than Pluto—and may have a large moon. Pete Albrecht

crunched some numbers and charted its

path in the sky for the upcoming year. Because of its distance—51

AU, 20% farther out than Pluto—it doesn't move very quickly.

Pete's planning on photographing it with his 12" Meade, but

due to the object's faintness at 17th magnitude, it will take some

practice, and might have to wait until EL61 can be seen high in

the sky in full darkness, which may not be until early winter. Oi

veh. It's raining new planets in here. Yesterday morning I first

heard about object 2003 EL61, a Trans-Neptuanian Object in our solar

system's Kupier Belt: the dustbin beyond the major planets where

debris from the creation of the Solar System gathers. It's big—perhaps

bigger than Pluto—and may have a large moon. Pete Albrecht

crunched some numbers and charted its

path in the sky for the upcoming year. Because of its distance—51

AU, 20% farther out than Pluto—it doesn't move very quickly.

Pete's planning on photographing it with his 12" Meade, but

due to the object's faintness at 17th magnitude, it will take some

practice, and might have to wait until EL61 can be seen high in

the sky in full darkness, which may not be until early winter.

But heh—a few hours later, yet another discovery was announced,

of yet another planet-sized body out "where God lost his shoes,"

as country people say. Object 2003 UB313 is even larger, almost

certainly larger than Pluto, and much farther out: 97 AU, which

is almost three times Pluto's distance from the Sun, and at a 44°

angle from the plane of the Solar System, where planets aren't supposed

to be.

Note that these were announcements, not discoveries. Both new worlds

(people are getting into fistfights over whether to call them planets)

were discovered in 2003, and their discoverers were holding out

for more data to help pin down their orbits, albedos, and so on.

There is yet a third large body discovered earlier this year, 2005

FY9, about which little has been published.

Peculiar circumstances forced announcement of 2003 UB313: People

were reading the logs of the discovery team's telescope on the Web,

and had begun to wonder what they were looking at, since no other

notable object is at that precise location. So other people began

looking, and eventually, the extremely faint object was photographed.

Pertinent stories are here,

here,

here,

and here.

If it all sounds confusing, you're right. I haven't entirely sorted

out the research politics yet, and we may not get the full story

for awhile.

Still, it's legal to speculate about the objects themselves. What

I think we have here are immense comets, so big that the inner

planets' gravitational fields have not perturbed them onto Sun-grazing

paths. They are a matrix of gravel and boulders embedded in frozen

gas rather than rockballs like Mars or gas giants like Jupiter. The

rocks may have gravitationally migrated to the objects' centers, and

one wonders if the gases have frozen out in layers by density, as

Larry Niven speculated in his 1966 novel, World of Ptaavs.

We may wonder for awhile; just getting there would probably take 100

years using current technology. In the meantime, does anybody else

have any new planets to announce? The line forms here. No pushing.

You'll all get your chance.

|

July

29, 2005: Embedded Database Engines and DLL Hell July

29, 2005: Embedded Database Engines and DLL Hell

(Read yesterday's entry if you haven't

already.) Several people have written to suggest database engines

for Aardblog, and a few asked a very good question: Why not just

install MySQL on the client, and thus use MySQL for both the client

database and the server that mirrors it?

Answer: I want the database engine embedded in the Aardblog application.

I'll use a separately installed engine if I really have to, but

I have a peculiarly intense animus against cutting an application

into several independent blocks of code. To do so is the road to

hell...DLL hell, specifically.

I have a strong bias toward single-block applications. Outside

of standard OS calls, I want everything that the app does to exist

within one monolithic .EXE file. The reason: Otherwise, there is

no way to guarantee that the code library environment under which

an application was compiled and tested will be identical to the

code library environment under which the application is run.

Ok. Example time. Suppose you create the DogMatic kennel manager

to use the MyDataBox database engine as a client-side database.

DogMatic V2.0 was developed using MyDataBox V3.5. As long as DogMatic

2.0 and MyDataBox 3.5 are both installed, everything's cozy and

works.

Alas, the CatHouse cattery manager was written to use MyDataBox

V3.55. If Roscoe's Puppies & Kittens installs CatHouse after

DogMatic, MyDataBox will overwrite its 3.5 release with its 3.55

release. Supposedly that's OK, because there are no API changes

between 3.5 and 3.55. MyDataBox does not require separate installation

of 3.5 and 3.55.

No API changes. Sure. However, My DataBox V3.55 changed certain

under-the-covers memory caching techniques, supposedly "transparently"

but with unanticipated consequences. DogMatic works with MyDataBox

V3.55...for awhile. Then something weird happens, memory management

burps, and MyDataBox writes a corrupted buffer to disk. Abruptly,

poor Roscoe loses everything he has on the puppy side of his business.

If MyDataBox had been embedded in the DogMatic .EXE file, this

could not have happened. If application and database engine are

inextricably glued together, DogMatic can only use MyDataBox

V3.5. Sure, you could argue that if MyDataBox's developers had really

ensured binary compatibility between their 3.5 release and their

3.55 release, this wouldn't have happened. Sure, and if we had a

time machine we could go back and strangle Adolph Hitler in his

cradle. Get real, people!

A great deal of Windows' flakiness is due to unrelated chunks of

code heedlessly calling one another whether or not the APIs involved

are really identical...or just mostly identical. Syntax matters,

but so do sematics. Whether or not the calling conventions and parameters

are identical, what is done with the parameters matters crucially.

Designer/programmer assumptions matter. All kinds of things

matter, and matter in ways that we can't anticipate up front. The

only way to shovel all these problems out the door is to minimize

the circumstances under which one independent block of code calls

another. OS calls probably can't be avoided, but there is no ego-free

reason for an application to call anything that isn't a highly

standard and well-understood component of the OS.

Back in 1999 I bought DBISAM,

an embedded database engine for Delphi, and have used it with great

success ever since. Alas, it costs $250. What I want is a simple embedded

engine based on the VCL. It doesn't have to be open source, though

I'd like something that doesn't have to be paid for. Some readers

have sent in some suggestions, and I'm looking into all of them. Will

report back in upcoming days.

|

July

28, 2005: Thoughts on Aardblog July

28, 2005: Thoughts on Aardblog

Aardblog is still a live project here, though everything I've done

on it so far is conceptual: Database schemas, UI sketches, etc.

I made a decision the other day that's pretty contrarian: All

content will be maintained in a local database, by a local Win32

client. The server-side MySQL database is literally a mirror. When

a new entry is created, or an old entry modified, it's stored locally,

and the local entry is marked as "dirty," so it will be

uploaded at the next connection to the server-side database. Basically,

all content in the blog will be present both on the local system

and on the remote database.

A lot of server-side freaks and going to roll eyes at this—duplicate

data! wasted space!—but I have strong reasons: I make a fair

amount of money writing, and the first thing I always ask is: Who

controls my content? Where does it live? Can I get it out of

a server or file format once it's in?

There are other issues as well. What happens to all your entries

if HypotheticalBlogHost.com goes under and the server goes down?

If you don't have it stored locally, it's gone. Could some company

purchase a blog hosting site and claim ownership of all the content

under some weird small print or interpretation of small print? Thanks,

but I want my words and pictures to be right here under my own roof

and in my safe deposit box. I may not be able to keep some kleptocorp

from using my content under a questionable rights agreement, but

I definitely want to have it all in my own two hands, irrespective

of where else it may be.

The wasted space argument is bogus. ContraPositive is one of the

oldest blogs on the Web, and everything it includes—text, photos,

almost 2,000 entries posted since 1998—doesn't even crack 50

MB. I have half a terabyte of disk here here locally. 50 MB of local

storage is nothing.

And beyond all that, Web-served content editing sucks. Period.

There are two coding tasks:

- A win32 client in Delphi, which handles all editing and stores

content in a local database. On command, it connects to the remote

server and uploads whatever doesn't already exist on the server.

- A server-side PHP program that serves up the blog to the public

at large by pulling data out of MySQL and formatting it for delivery

to a generic Web browser.

#1 will not be too tough; it's really a pretty simple database

app, and I've known SQL for fifteen years or so. The queries that

allow selective division of the content database into topic-specific

blogs is the easiest part of it, in fact. (I'm amazed at how tricky

it is to connect to a remote SQL database from Delphi. Geez, guys!)

The PHP app will be tougher, as I have no experience with PHP and

will have to get up to speed. However, I have a local server here

in the basement with PHP/MySQL/Apache already installed, configured

and ready to go. The rest is just practice.

I'm currently entering some entries (real entries, if short ones,

from back in 1998) into the MySQL database through PHPMyAdmin so

I can begin putting some Delphi and PHP test code together. PHP

first; I'll feel like I've achieved a major victory if I can serve

up some entries in a simple format.

I don't want to be in the software business, and ideally I'd like

to turn this loose as an open-source project on SourceForge, using

all free components, starting with the formidable Turbo Power Orpheus

suite. The kicker there is the local database. I hate to say it,

but I don't like FlashFiler very much, and I'm not sure what other

free relational database engines are available. That's another research

item.

I'll keep you informed as the project evolves.

|

July

27, 2005: Virtual Zones in a Hypervised OS July

27, 2005: Virtual Zones in a Hypervised OS

If I were to design a new OS from scratch (not that I would be

capable of anything beyond the highest-level concepts) I think I

would make heavy use of the new hardware virtualization features

to be present in the next generations of both Intel and AMD CPUs.

What I would do is pretty simple: Create an underlying hypervisor

on the Xen

model (which requires the cooperation of its virtual machines) and

then build the OS in several zones, each of which is itself a separate

virtual machine running its own mini-OS:

- A communications zone would contain all apps with network abilities.

This would include Web browsers, FAX programs, chat/VOIP programs,

and all other TCP/IP based utilities.

- An office information zone, which is where the user would install

office apps for word processing, spreadsheets, presentations,

drawings, and so on.

- A storage management zone, which would contain machinery for

backups, defragmentation, and so on. The file explorer would work

from this zone; however, nothing in any zone would write anything

to disk except through the services of the daemons; see below.

- A daemon zone, in which special services would run that would

monitor movement of information among the other zones. Nothing

would move across a zone boundary except by the intervention of

an appropriate daemon, which would do the moving. The daemons

would work according to very strict rules, and would be designed

to anticipate malware exploits. Executable items would not be

moved until they were first copied to a sandbox (in a hidden zone

inaccessible to the user) where they would be run and observed.

Anything that attempts any of several actions, from scanning for

files to tapping on the network port, would be quarantined pending

further research. I don't think that relying on virus/worm signatures

is enough. (The daemon zone might better be built into the hypervisor.

Hey, I'm just brainstorming here; OS architecture is something

I've never studied in depth.)

- Additional zones could be created by the user, for the installation

of specialty apps of whatever sort. I would create one for astronomy

software, another for programming, and probably yet another for

media work (video editing, etc.) Each major programming tool would

probably go in its own zone. I do all my Delphi work now in a

VMWare virtual machine, and that's where I'm building Aardblog.

Each zone would contain an independent operating system kernel,

and all zones could run independently—though if the daemon

zone goes dark, I think it would cripple the system. (One reason

to exile the daemons to the hypervisor.) This is a little like how

I understand the Mach microkernel works, but I don't think that

Mach makes any use of virtualization. The user would not be constantly

made aware of this zone partitioning, though I think it would be

cool to have the screen divided into different colored areas by

zone, with icons belonging to a given zone in a distinctly colored

area of the UI.

Anyway. Just an odd idea. I'm trying to decide how narrow the zones

should be: Should Web browsers and other Internet clients that deal

in executable content be isolated in their own zones? Should every

major app be its own zone? Or only those apps that can open executable

content? Keep in mind that every zone needs an OS kernel, so if

you have ten zones running at once, you're going to be losing a

lot of memory to code duplication. Maybe that's a Who Cares?—especially

once ordinary PCs routinely carry 10-20 GB of RAM.

The interesting thing about this concept is that it wouldn't have

to be coded entirely from scratch: We already have Xen for

a hypervisor, and both the Linux kernel and the BSD kernel are open

source. For all I know, somebody's working on it already. I hope so.

|

July

26, 2005: Odd Lots July

26, 2005: Odd Lots

- I've added Loren Heiny's Incremental

Blogger to the blogroll at left, and I recommend it as a superb

place to get the latest scuttlebutt on Tablet PCs. I'm researching

tablets right now, as I'll be acquiring a Thinkpad X41 Convertible

shortly.

- One of the cooler things I found scanning Loren's blog is the

Otter

tablet PC cases. The company makes waterproof, ruggedized

cases for PDAs, tablets, and other things, including (egad) cigars.

The selection is limited right now (basically to the Fujitsu Stylistic

4000/5000 tablets) but I'm hoping they'll eventually get one together

for the X41.

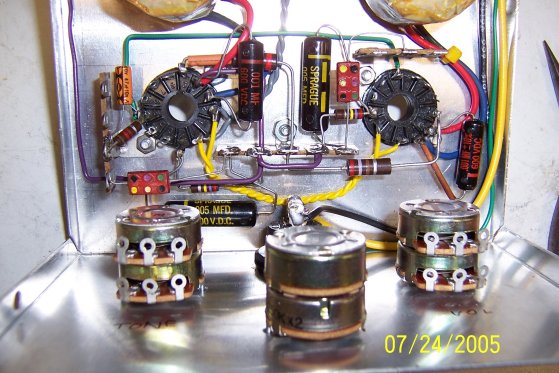

- Yes, the big audio blocking caps in my 6T9 stereo amp (see yesterday's

entry) are new old stock paper-dielectric Spragues, but the amp

is fused and will not run especially hot, so I'm not as worried

about the thing catching fire as some people might be.

- Also, really and truly, there is no particular advantage to

using coax as audio cable. I just do it because I have a lot

of coax, and don't need audio cable very often.

- If anyone would like to build a similar tube stereo amp without

as much fuss, the guys who designed the

6T9-based amp featured in the August 2004 Nuts & Volts

offer PC boards and parts kits. The circuit isn't quite the same,

but in truth there's only so many ways to make a 6T9 amplify at

audio, so there is a good deal of similarity between their circuit

and mine.

- Roy Harvey sent me a link to what may be the

largest stitched-together digital photo ever assembled, with

more than one billion pixels. It's something to see, and

the page has some nice information on handling very large images.

- I find it interesting, in perusing my Web server logs, that

the split between Firefox and IE has not changed significantly

since March of this year. Since then it's been 62-63% for IE and

24-25% for Firefox. Prior to March, Firefox's share had been climbing

significantly each month, sometimes by two full points. In August

2004, the first full month of stats that I have, IE was at 70%

and Firefox at 13.6%. Some of Firefox's gain since then seems

to have been at the expense of Mozilla (not unreasonable) and

Opera. All of these stats are on hit counts ranging from 120,000

last August to 170,000 in May. (Sectorlink lost some of my stats

for June, and July isn't over yet.) You have to wonder if most

of the people who are willing to (or can) move to Firefox have

already done so. Still, 25% is a lot.

- Cassini sent back some phenominally

weird VLF signals from Saturn, so NASA downconverted them

to audio and made a .wav file available. If you're going to do

a haunted house next Halloween, just put this one on endless loop,

and that's all you're gonna need for sound effects!

|

July

25, 2005: Building a 6T9 Tube Stereo Amp...Slowly July

25, 2005: Building a 6T9 Tube Stereo Amp...Slowly

I've been fooling with a hand-built tube stereo amp project for

almost a year now; see my entry for July

29, 2004 for the first mention of the project, and a photo of

the amp in progress in my March

5, 2005 entry. The project is interesting for a number of reasons,

but the least obvious is that I'm deliberately building it slowly.

The reason is simple: When I hurry I make mistakes. I

forget to solder connections, I use faulty parts, I leave out

components or connections entirely.

So what I've been doing these past several months is spending half

an hour on the project every so often, and cultivating the discipline

of carefully soldering in one component...and stopping. I don't

really need the amp, and I want it to look nice inside and out.

I'm trying to emulate the old QST style of every wire and component

running at right angles, though somehow, no matter what I do (and

it isn't always possible) I can't make it look quite as good as

they always did.

To avoid missing connections, I drew out the complete schematic

in Visio, and printed it to paper. Then each time I solder in a

component or a connection, I run a green highlighter over that component

or connection on the schematic. I also take the time to test every

single component before I solder it in, and wiggle the joint after

I solder it to be sure the joint is sound. I make sure I solder

in each component so that its markings are clearly visible from

above, so that I will not mistake one cap for another when tracing

the wiring or troubleshooting.

The big challenge in a project like this lies in arranging the

parts, and anticipating the need for terminal strips. I want the

wires and components to be neatly arranged and spread out so that

I can get a test probe in anywhere I might need to later on. The

fact that the 6T9 Compactron tubes require 12-pin sockets with very

small pin spacing makes part arrangement even tougher.

And furthermore, I want no unnecessary holes in the aluminum

box.

It's coming along nicely. The other day I got about as far as I

could go before wiring in the three dual pots (volume, tone, and

balance) which requires 12 separate shielded connections through

RG-174/U miniature coax. (I use that instead of shielded audio cable,

because I got a huge roll of it cheap at a hamfest years ago.) Because

the underside will be much tougher to photograph with the three

pots wired up, I took some pictures of the circuitry as it is now,

knowing it will never be quite as tidy.

I don't know when I'll finish it. I deliberately didn't set a deadline.

I'll post the schematic once I know the circuit works as designed.

I've tweaked the design a little, especially the input network (which

now has a balance control) and I don't want to publish something with

bugs. When it works, I let you know, and tell you how I did it.

|

July

24, 2005: Review of Spielberg's The War of the Worlds July

24, 2005: Review of Spielberg's The War of the Worlds

Most of my feelings about any film adaptation of Wells' The

War of the Worlds can be summed up this way: Film versions

of Victorian novels should be set in Victorian times. (When

will we learn?) I saw Spielberg's new film last Friday night, and

while it had its moments, they were few, and in general, it was

a disappointment. There are a few spoilers below, but there isn't

much to spoil; anyone who's ever read Wells'

novel (or the

wonderful Classics Illustrated comic book version) knows precisely

how the plot plays out.

About half of my disappointment stemmed from Wells' Victorian concepts

being set in 21st century New York. Slow-moving, philosophical British

novels need to be set in a time when the people, culture, and situations

in those novels don't violate our understand of that time. The Victorian

world knew relatively little about biology and Mars, and had no

radar, no jet fighters, and no nuclear weapons. Because today we

could have seen them coming if they tried to land in conventional

spacecraft, Spielberg has them sneak in under the cover of weird

storms, having hidden fighting machines on Earth long before we

evolved from lower animals.

Much of the film simply doesn't make sense for this reason. Judging

by their mode of travel, Wells' original Martians had never been

to Earth before and were clearly desperate and ignorant of conditions

here. In Spielberg's retelling, the aliens have been visiting Earth

for what may have been millions of years, burying thousands of 25-story

metal tripods just underground (Huh? Nobody ever hit one digging

a mine, a well, or a subway tunnel?) and waiting until we evolved

a technological civilization to attack us. Knocking over classical

Greece would have been a lot easier, no? And if they wanted us for

food, as the film implies, establishing caveman farms could have

been done with far less work and capital equipment 100,000 years

ago. Worst of all, if they were a star-traveling species and had

been here for so long, how in hell could they not know about

the dangers of microbial life? And (in an objection I also have

to Wells' original story) why didn't alien microbes kill us as thoroughly

as ours killed them? How the aliens got from the stormy skies down

into the still-buried tripods is another puzzle, explained so briefly

and unconvincingly as to seem like an afterthought glued on to plug

a plot hole. "Sheesh, guys! We forgot to explain how the aliens

got down into their buried fighting machines!"

Yes, I'm prepared for emails bearing tortuous explanations, but

Occam's Razor applies to film scripts as much as anything else.

Beyond that, lots of little inconsistencies insult our intelligence.

An EMP that takes out every single car and truck throughout the

Northeast leaves digital cameras and camcorders unscathed and functioning.

If the EMP destroys alternators installed in cars, it would also

destroy spares sitting on garage shelves. Hundreds of birds roost

on what look like still-sealed fighting machines, as if they know

there's dead alien meat inside and just can't figure out how to

open the can. Etc. The guy thinks we're idiots.

The other half of my discontent is simpler to explain: We see far,

far too much of Tom Cruise looking anguished and Dakota Fanning

freaking out, and way too little of any sort of "war".

We see the well-designed tripedal aliens (not Martians; the film

never states where they come from) in poor light for all of five

minutes, and the iconic tripod fighting machines for perhaps

fifteen or twenty at most. Spielberg supposedly spent an immense

amount of money on this project, and I think he got taken. The effects

are well-done, but compared to something like The Lord of the

Rings, they occupy a minor position in the film and mesh badly

with the human drama in the foreground.

The film is tense, but the tension gets old after awhile. The little

girl Rachel was annoying and completely unnecessary, and the rest

of the human drama was overwrought. A seeming eternity is spent

in the gloomy basement of an old farmhouse, dodging first alien

tentacles and then the aliens themselves. We see a lot of American

military hardware, but rarely in the same frame with the alien tripods.

Hordes of people trudge slowly around rural Connecticut like extras

from Night of the Living Dead. I kept wanting something to

just happen.

I had the same general reaction to M. Ramalamadingdong's pretentious

and excruciating Signs: More (and smarter) aliens. Less Mel

Gibson and other bad actors chewing on the curtains.

The great tragedy of Spielberg's The War of the Worlds is

that it has evidently buried the

authentically Victorian period adaptation of Wells' novel. It's

been consigned to DVD and will see no action in theaters. Supposedly

I can rent it, and I'll begin looking for it. I may be disappointed,

but I suspect I won't be insulted.

(Now, does anybody want to know how I would have scripted a

modern-day setting of WOTW?)

|

July

23, 2005: Odd Lots July

23, 2005: Odd Lots

- Frank Glover sent me a

pointer to a blog that suggests persuasively that not all

suicide bombers may know that they themselves are going to blow

up too. The recent London bombers had paid up their parking fees

and had the bombs in backpacks, suggesting that they were planning

on leaving the bombs somewhere to blow up after they escaped.

(Read the item; there's more than I can summarize here.) Whether

or not this is true, I think we should all circulate the possibility

until it becomes a meme, which might make it just a little

harder to recruit future bombers. Not everybody believes in a

cause enough to die for it—and there may be a sort of "bombers'

remorse" effect that might generate a few more cold feet

if we fed it.

- The next major version of Windows, now code-named Longhorn,

is

going to be called Windows Vista. Was XP, now Vista. Ya gotta

wonder what's wrong with Windows 2002 or Windows 2006. Actually,

what's wrong with "Windows 2006" is that it doesn't

sound like there's much there worth upgrading to, which is the

case more often than not. I still think Windows XP is just Windows

2000 in a clown suit.

- I spent some late night nostalgia cruising through Oddball

Comics, a blog that dips into the stacks of long-past comic

books for the most peculiar examples. I was surprised to see how

many I recognized, considering that I only saw comic books in

my cousin Ron's basement or at Boy Scout campouts in the early-mid

1960s. I was never much for conventional superheros, and preferred

things like Monsteroso

from Amazing Adventures #5 or Metal

Men, who were

robots whose personalities mirrored the characteristics of various

metals. (Anthropomorphizing gallium—what a concept!)

Lotsa fun. Although he doesn't mention it, I should also point

out the Catholic comic book Treasure Chest, which ran a

famous series called "Godless

Communism" when I was in third grade. You might consider

that oddball (or just surreal) but it has nothing on a story arc

about a bear and a wainwright that ran in the mid-1960s that I

have been unable to find. (Somebody, somewhere, has a stack of

these things in the basement, I'm sure.)

- People who prefer clicky keyboards (technically called "buckling

spring" keyboards) should read this

page from Dan Rutter, which is a good summary of your IBM-centric

options, though remarkably, Dan doesn't even mention Northgate.

Most keyboards were clicky until IBM lost control of the personal

computer market in the late 1980s, and those of us who learned

computing then for the most part prefer them as they were. I like

Dan's style; in closing, he says: "Computer users are used

to hardware that's worthless in three years and useless in five;

clicky keyboards aren't like that. You could leave one of these

things to your children in your will. Or be buried with it, like

some kind of nerd Pharaoh." Heh. Indeed.

- More nostalgia: Backyard

Artillery cites a lot of things we knew and loved in the 50's

and 60s, like cap bombs and ping-pong ball rifles. I'm dubious

about the fully automatic rubber-band machine gun (you have to

crank it and then it shoots rubber bands) but it's a marvelous

concept nonetheless.

|

July

22, 2005: Update on My Personal Spam Wars July

22, 2005: Update on My Personal Spam Wars

I've been having intermittent problems with both Poco Mail and

POPFile, and I've been thinking about whether a major email strategy

change is in order. If I can figure out how to get my mailbase out

of Poco and into Thunderbird I may jump. Maybe this is a good opportunity

to lose about, oh, 10,000 messages from the mailbase...

POPFile's accuracy has come down significantly in the last year,

from 99.6% to its current 97.75%. I can still live with that, but

I'm not sure why the drop, except that it corresponded roughly to

my move from Interland to Sectorlink and the corresponding 80% plunge

in my daily spam count. It may be that when 95-97% of your mail

is spam there are just fewer opportunities for false positives.

Now only about half of my mail is spam, so each individual message's

butt is statistically a little more likely to get hit in the crossfire.

POPFile needs a "teaching magnet" but it's really the

best weapon we have right now. I just completed a three-week test

using keyword filtering to see how well I could block spam based

on "payload" domains in the message body; that is, the

destination URL or (much more rarely) phone number that the spam

was intended to convey to the recipient. The payload is the only

thing the spammer can't obfuscate, or the campaign would fail, so

it's a reasonable thing to block on.

However...

Over the past three weeks, I discovered that the daily rate of

new payloads was between 30 and 40 percent. In other words,

every day in the last three weeks, one third of my spam was

pointing to domains I had never seen before and therefore had not

blocked. I didn't see any new obfuscation tricks. I like those,

because they're spammer-specific and can be filtered on. Nope, the

sole strategy of the zombie spammers is now to rotate payload domains

on a near-daily basis. This doesn't leave us much except Bayesian

filtering, of which POPFile is the most highly evolved example.

By the way, reader Andrew Colbeck confirmed what Darrin Chandler

suggested in my July 1, 2005 entry: That

spammers do not generally cache DNS lookups. In other words, once

a spammer has an IP for you, he'll use that IP without further verification,

to avoid the time cost of a DNS lookup. About 80% of my spammers

are therefore probably still hammering the IP address of my old

POP server at Interland. I'm a little surprised they don't "freshen"

their lists now and then. I would expect something more than about

a 10% increase in my daily spam count in six months, but that's

all I've seen.

If we were all using IPV6, we could retire IP addresses every month

or so, and stay ahead of these "optimized" spammers that

way, but our current IP addresses are too scarce for that. Bulk domain

sales have made domain names essentially disposable. My suggestion

that public DNS records contain a unique code for each domain owner

would be extremely useful: With that, we could just tell our software

to block every domain owned by the same people who own shitheadmarketing.com.

They can buy domains in bulk, and we could block domains in bulk,

and the best thing is, it wouldn't even violate domain holders' privacy.

The code would contain no information, but would simply allow us to

identify which domains are owned by the same someone—and we wouldn't

have to know who that someone is. Alas, even if the political issues

could be solved, there are practical challenges in that no single

agency registers domain names, and thus managing a unique domain owner

code across all domain registrars would be a huge logistical problem.

Damn, I can dream, though.

|

July

21, 2005: War Against the Weak, Concluded July

21, 2005: War Against the Weak, Concluded

The big question that Edwin Black's War Against the Week

fails to address is simply, What were these people thinking?

How could eugenics have gotten so far and stayed "legitimate"

for almost fifty years? Some of my thoughts here:

- Racism itself was legitimate (meaning legal and accepted by

ordinary people) until well into the 1950s. Our sensitivity to

race issues is in fact a very new thing.

- Eugenics played to a visceral fear that "our tribe is being

outnumbered by the other tribes." This fear is still with

us (it's in our genes, I suspect) and we sense it today in a lot

of discussions running from political parties to immigration to

the rise and fall of religious traditions—but people are

no longer seriously talking about murdering or sterilizing the

other tribes. (Not in public, at least.)

- Utopianism was a very big thing in the century1850-1950.

Most utopian schemes are both elitist and coercive or even totalitarian,

and none of them work for long, if ever. Eugenics was very much

a utopian idea, and just as lame as all the others.

- Eugenics was a favorite idea of the cultural elite among the

urban moneyed classes and the universities. (Ordinary people in

the white middle class did not widely embrace eugenics and often

protested vehemently against it.) The ones who pushed eugenics

the hardest were the same ones who dominated what passed for mass

culture at that time. (How many Black folks had seats at the

Algonquin Round Table?) Thus, eugenics may appear to have

been more widely embraced than it actually was because those who

embraced it were those who did most of the writing and defined

most of the culture.

However, my favorite personal theory involves a strange psychological

shortcoming present in many people: They get fixated on an idea,

and can't put it into perspective before they experience it directly.

Years ago I read an article in the Rochester, NY Sunday paper about

some fool who moved from Manhattan to Rochester, and one day decided

that he absolutely had to have a bag of onion bagels from

his favorite grimy little deli in Brooklyn. It wasn't until he had

driven most of the 300 miles to New York City that he realized what

a total idiot he was.

Ugly ideas often sound compelling when they can be embraced only

in the abstract. Much of the big noise in the Libertarian movement

comes from addle-brained anarchists who have no idea what the consequences

of genuine anarchy would be. Wave a blood-smeared real-world example

in front of them and they're likely to object, Those people in

Somalia just don't know how to do anarchy correctly! (We need

an Anarchy Corps so we could send our home-grown anarchists over

there to show them how it's done. One-way tickets will suffice.)

Sterilizing "defectives" sounds great until you (or someone

close to you) gets classified as "defective" and ends

up a statistic. (It happened to between 70,000 and 90,000 Americans

between 1900 and 1960.) I keep thinking of upper-middle class liberals

whose mindless chant is "Soak the rich! Soak the rich! Soak

the rich" until the Feds say, "Sure thing. Guess what?

You're rich!"

Ideas have consequences. Always. The inability to imagine

consequences is a tragic human failing. I think that that failing

was the reason that people who would never consider clubbing a handicapped

person to death themselves would in all earnestness nod approvingly

when they read some rant by some university racist talk about "lethal

chambers" for the "genetically unfit."

Anyway. War Against the Weak is required reading for people

who think that we live in a morally debased era. Not true. Piddly

things like promiscuity or flag burning vanish into insignificance

next to ideas like eugenics, which ultimately led to Auschwitz. The

more I read history, the more I appreciate our own era, which even

with its flaws is the most humane era humanity has ever seen.

|

July

20, 2005: Odd Lots July

20, 2005: Odd Lots

I just got back to Colorado Springs, and the heaps of suitcases

in the middle of the living room floor whisper that there will obviously

be no time today to sum up on War Against the Weak, so clearing

a few odd lots will have to suffice:

- I did some significant work to my

Tom Swift, Jr. page a few weeks ago, including some edits

and a few more cover scans. I'm getting close to being able to

replace the ancient duntemann.com front page; the page is done

and just needs the creation of a few more things before I can

post it.

- Pete Albrecht sent me a link to a

roll-off observatory created using 80/20

extrusions and connector components. Although the observatory

shown is a commercial product, there's nothing in it that a savvy

tinkerer couldn't do with hand tools. 80/20 is very cool (they

call it "the Industrial Erector Set", which is bang-on)

and I hope to do something with it someday.

- From the cautionary tales department comes Doomed

Engineers, a page summarizing brilliant men who came to bad

ends, mostly because they were not as wise as they were smart.

The poster child here is Gerald

Bull, who was so obsessed with the idea of shooting projectiles

into orbit with big guns that he tried to build a monster artillery

piece for Saddam Hussein and got himself rubbed out by the Israelis.

Bull didn't invent the concept, which goes all the way back to

Jules Verne, in his fine old 1879 novel The Begum's Fortune,

which should be online somewhere but I haven't had the time to

find it. Thanks to Pete Albrecht for the pointer.

- Finally, while Carol and I were crossing from Terminal 1 to

Terminal 2 at Chicago O'Hare yesterday, we ran across a little

kiosk where Lenovo (to whom IBM recently sold its Thinkpad line,

along with most other IBM PC stuff) was doing hands-on demos of

the

Thinkpad X41 Convertible tablet PC. A young woman took me

through it, and I was most pleased, pleased enough to feel like

I'll grab one once my X21 is fully depreciated in a few months.

If ebooks are going to happen, machines like this are going to

have to go mainstream first. More as I learn it, but it was nice

to actually hold an X41 in one hand and my venerable X21 in the

other hand. They weigh the same, and are almost exactly the same

size, which is small.

|

July

19, 2005: War Against the Weak, Continued July

19, 2005: War Against the Weak, Continued

(Continuing my review of Edwin Black's book, War Against the

Weak, begun July 18, 2005.)

Among the photo plates in War Against the Weak is a still

from The

Black Stork, a low-budget 1917 film written by a Chicago

newspaper reporter and produced in Hollywood. The

still shows a mother and father standing before a dead newborn,

whose soul is depicted rising into the arms of a scruffy-looking,

miasmal Jesus. Typical silent-era tearjerker material, with a crucial

difference: The parents decided that the infant was not fit to live,

and killed the poor thing. A glossy poster promoting the film read,

"Kill Defectives, Save the Nation, and See The Black Stork."

As appalling as it might seem to us today, The Black Stork

was very popular in 1917. Chicago's LaSalle Theater played the movie

continuously between 9 AM and 11 PM, and it ran intermittently in

theaters around the nation for almost ten years. It was the brainchild

of Dr. Harry Haiselden, chief of medical staff at Chicago's German-American

Hospital. Haiselden was a man of gleeful coldness who makes the

most indifferent abortionist seem like Santa Claus. He not only

admitted infanticide (though neglect and refusal to treat or provide

basic human needs to infants) but declared that all physicians did

it, and that it was a necessary step to keep defective individuals

out of the human gene pool. He laughed at people who expressed concern

for the euthanized infants, and quipped that "Death is the

best disinfectant." Several prosectors attempted to convict

him of murder or medical malpractice, but none succeeded.

One of the great strengths of Black's book are its recall of minor

incidents, mostly forgotten by history, like Dr. Haiselden and The

Black Stork. Eugenics was not freakshow stuff in 1915. It was

the material of public debate, and the eugenicists were taken seriously,

even when they suggested, as did the author of the popular textbook

Applied Eugenics, that genetic defectives (a term never crisply

defined but often assumed to those of include low intelligence and

lacking moral fiber) be killed.

On the negative side, Black goes to great lengths to exonerate

Margaret

Sanger of racism. Sanger was an early feminist and the person

who coined the term, "birth control." She's become a feminist

hero as being the first person to demand that women have the freedom

of choice about sex and childbearing. And although she was not primarily

a racist (far more of a Malthusian, actually) she expressed belief

throughout her long life that people who could not prosper in society

should be forcibly sterilized, even into the 1950s, knowing that

many or even most of the very poor were nonwhite. (See this

article.) She surrounded herself with some of the worst American

racists of her time, including Lothrop

Stoddard, author of The Rising Tide of Color Against White

World Supremacy, and approved of most of the elitist thought

coming from her friend H. G. Wells in the last years of his life.

It's impossible to understand either Sanger or Wells without understanding

the Fabians

(a British lefty utopian clique most active between the Great Wars)

but Black does not mention them even once. When Sanger finally broke

with organized eugenics, it was because leaders of the eugenic movement

(virtually all of them men) could not abide her strident feminism

and threw her out. I'd rather have honesty, and won't insist that

Sanger's support of eugenics casts doubt on her feminism. Nonetheless,

no one who had fingers in the eugenics movement came away with clean

hands.

The most disturbing facts among the many presented in War Against

the Weak are accounts of state laws passed in the early 1900s

providing for (or even requiring) sterilization of the unfit, and

regulation of marriages to prevent unions between whites and those

of other races. (Unions between partners both of nonwhite races

were not illegal and not discouraged.) Between 70,000 and 100,000

Americans were forcibly sterilized between 1900 and 1960, and countless

interracial marriages were prevented, their intended partners harassed

and sometimes charged with felonies. Although enforcement became

uncommon after World War II, some of those laws remained on the

books well into the 1970s.

As most people know, the most enthusiastic proponents of eugenics

were the Nazis, and until they provided real-world illustration

of eugenics in action (rather than merely university lounge conversation)

eugenics retained its place in American and world thought.

I'll conclude tomorrow.

|

July

18, 2005: Review: War Against the Weak July

18, 2005: Review: War Against the Weak

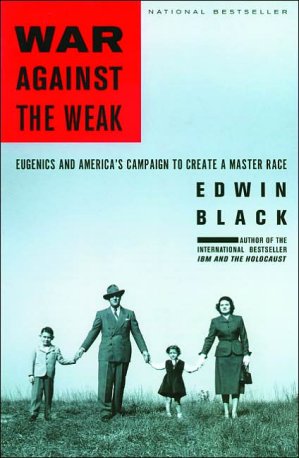

For

this year's beach reading I chose Edwin Black's War

Against the Weak, which I stumbled across in my ongoing

quest to understand the roots of the Roman Catholic Church's peculiarly

intense (and suicidal) prohibition of preventive contraception. For

this year's beach reading I chose Edwin Black's War

Against the Weak, which I stumbled across in my ongoing

quest to understand the roots of the Roman Catholic Church's peculiarly

intense (and suicidal) prohibition of preventive contraception.

War Against the Weak is a solid and very readable (if slightly

shrill) history of eugenics, which in turn is nominally the quest

to improve the human race through selective breeding. Most people

who have looked into the topic even briefly know that the whole

thing was a sham, but few, I suspect, understand just how deep and

how ugly a sham it was. Eugenics is perhaps the purest example in

all history of bad people using bad science as an excuse to impose

their own biases on society at large.

Very shortly after an obscure Augustinian monk named Gregor Mendel

described some simple rules of inheritance that he had observed

in peas grown in a monastery garden, the world's educated elite

seized on the concept as evidence that all human traits were inescapably

heritable. Some of it may have been the when-all-you-have-is-a-hammer-then-everything-looks-like-a-nail

effect, but the greater part of the enthusiasm was far simpler:

It was the perfect excuse to declare any group not in favor with

the university elite "genetically defective." Prior to

Mendel, bias against the poor, the unsophisticated, and the nonwhite

was just that: Bias. After British mathematician Francis Galton

popularized the notion of heritable human traits in the 1880s, he

coined a new word, "eugenics," to stand for the goal of

improving humanity through breeding. Galton did not know of Mendel's

research, and though he described the "what," he was clueless

as to the "how." Mendel provided the "how,"

and that's when the party began. Edwin Black documents the dark

party of eugenics, from its origins in Victorian England to its

end in the Nazis' Final Solution.

The really nasty part of eugenics is how much of its history occurred

right here in the USA. American organizations, including the Rockefeller

and Carnegie foundations, funded eugenic "research" and

the popularized the concept through books and journals. American

universities, never able to resist an intellectual fad that eventually

makes them look like mean-spirited idiots, provided researchers

and academic credibility. Some of the most influentual men of that

era, including Alexander Graham Bell, Robert Yerkes, George Bernard

Shaw, and H.

G. Wells, bought into eugenics and argued for government measures

including mass sterilization of the "defective" and rigorous

regulation of marriage to prevent the "unfit" from reproducing.

No sooner did the British invent the "lethal chamber"

as a humane way to kill stray dogs and cats circa 1900 than the

worldwide eugenic community (including groups

in nations as progressive as New Zealand) began to discuss in

their journals and conferences whether the best way to solve the

problem of the genetically unfit was simply to gas them.

No, I didn't initially believe it either, but Black provides an

immense body of research to support the book; his footnotes and

lists of sources take 80 pages alone. I don't much care for historians

who insist on telling me how outraged I should feel (as Black does

a little too often) but the material itself is so appalling I can

understand him getting a little unhinged about it. In truth, Black

is not a historian but an investigative reporter, which explains

the general tone of the book.

So where did the passion for eugenics originate? That's no mystery,

and Black explains it well: The last quarter of the 19th Century

saw unprecedented migration from Eastern Europe to Western Europe

and the United States, and of rural Blacks from the southern US

to the urban north. The educated and moneyed classes saw their own

racial group being swamped by great numbers of browner and less

educated people, who (of course) "breed like rabbits."

Popular books with titles like The

Passing of the Great Race and (egad) The

Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy fed the

fires of racial paranoia. Racism as an unremarkable fact of ordinary

life in this period is well-known, but most people think of such

racism as a moral flaw within individual human beings. Eugenics

systematized racism and tried very hard to give it the glint of

scientific integrity and the force of government authority.

The scary thing is the degree to which the eugenicists succeeded,

and I'm not even talking about the Nazis. Depressed yet? If not, patience:

The worst is yet to come. More tomorrow.

|

July

17, 2005: Vacation Recovery July

17, 2005: Vacation Recovery

Carol and I got back to Chicago O'Hare a few hours ago, and now

begin the process known as "vacation recovery." We're

taking a day or so here to visit, and then will be flying back to

the Springs this Tuesday afternoon.

We had a great time, and have half a suitcase full of salt-water

soggy clothes to prove it, but as I've mentioned here and elsewhere

before, I have become very impatient about getting answers to even

minor factual questions that occur to me. While sitting on the beach,

I recalled an old New Colony Six novelty song from the late 1960s,

and I wanted to look up the lyrics for "Wingbat Marmaduke"

right now. Later on, it came up in conversation that Tommy

Lee Jones had a role in Love Story, which I found very hard

to believe. Where's IMDB when

you need it? While poking through the local Anglican cathedral,

a hymn

popped into my head, but I was missing one of the lines of the

melody. I wanted to bring up Cyberhymnal

and play the

MIDI file, with a sort of fiery impatience that startled me.

None of these things are important (and there were dozens of others)

but they're also precisely the sorts of things that come up when

you empty out your brain and refuse to think of anything important

in an organized manner beyond when the next high tide (or maybe

lunch) will occur. So part of my vacation recovery will consist

of emptying out my mental file of trivia to research, just as soon

as I can get over to Panera Bread—though probably not until

tomorrow morning.

And if you're reading this, I've already verified Tommy

Lee Jones' role in one of the worst movies ever made (his first

film appearance, in fact) and can play "In

Babilone" in my head in its entirety. (The Wingbat Marmaduke

has eluded even the long reach of the Web. I'll play it when I get

home.) Little itches matter the most—especially when you can't

scratch.

|

July

12, 2005: The Art of Photochemicals July

12, 2005: The Art of Photochemicals

Bob Halloran wrote to suggest (a little bit sadly) that ours may

be the last generation that knows how to use a darkroom. I agree.

In fact, even among the Boomers darkroom tech was getting pretty

geeky by the early 70s, because of the availability of cheap and

quick snapshot services down at the drugstore. My dad tinkered with

color-slide darkroom techniques when it became possible circa 1950,

but set aside that (and most of his several other hobbies) when

the kids started coming along. I lacked an enlarger, but I had a

small bellows camera that took 120 film, which is a large enough

format to produce contact prints of a useful size. I played around

with b/w development (Dektol!) in the basement, particularly with

lunar and planetary photos taken on my crude 8" Newtonian scope.

What bothered me then about darkroom work was that there was a

lot of black art in it. I had a hard time duplicating my

successes and avoiding my failures. There were broad book-learned

techniques to be followed, but there also seemed to be a lot of

wildcards in the process, and eventually I set it aside, not finding

the fascination for photography that I had found for telescopes

or electronics.

I think what attracts a lot of people to digital image processing

is that it's repeatable. There's some black art in it to

be learned, but no wildcards—if you study what's going on closely

enough, you can quantize every adjustment and transition and do

it again identically. This is especially true of color work. A color

chart is purely conceptual in chemical photography. In digital photography,

the chart maps to real numbers (which produce real pixels) inside

a real image. Given the same image, the same manipulations will

create the same results, which is much more repeatable than holding

your thumb over a dark part of the image for a second while you

turn the enlarger light on.

Maybe this is a loss, but maybe not. I think that chemical photography

will continue for a good many years, rather like tube audio, even

if 98% of photography enthuasiasts go digital. And just as tube

audio hobbyists have benefited by better passive components born

of solid-state science, so chemical photography guys will benefit

from better treatments of color theory in the press, better optics,

and perhaps other things as well. We just know more than

we used to, in almost every facet of every field, including optics,

color, and image manipulation.

To the contrary, maybe it's one of those increasingly rare win-win

situations. I hope so. And I'll be glad to let the chemical photography

guys have their Dektol (or whatever it's called 40 years later) and

their black art. Me, I just want the pictures.

|

July

9, 2005: On Vacation for a Bit... July

9, 2005: On Vacation for a Bit...

...so if entries here are a little sparse, bear with me. I'll do

what I can. I never much liked writing entries in airports. We'll

see how it goes in the hotel.

In the mean time, my current laptop depreciates fully early next year,

and I think I know what

my next laptop will be.

|

July

8, 2005: The Two Megapixel Difference July

8, 2005: The Two Megapixel Difference

I've had a two megapixel Canon Digital Elph camera since Christmas

2000. It has worked flawlessly all this time, producing images that,

when printed using any of several printing technologies, look as

good as almost any of the photographic prints that came out of my

several "automatic" 35 mm film cameras over the years.

This past Christmas, I gave Carol a four megapixel Kodak digital

camera and matching printer dock. It's been interesting seeing the

prints that her camera produces, on its own printer and other print

technologies.

They seem fundamentally different somehow. They're sharp, razor-sharp,

so sharp that my eye/brain partnership looks at them and tells me,

That's not a snapshot. That's something entirely new. It's

a whole different way of remembering, because there's so much more

"remembered" in the photos. We can see things in the prints

that we could never see before: The moist glisten and texture of

Q-Bit's little black nose, or contours in Carol's hair that had

always been ever so slightly blurred out in older prints.

The improved resolution is, of course, a partnership between a

camera that captures finer detail, and a printer that can express

finer detail. It's not just the camera. Chemical photographic film

and paper have inherent limitations of resolution, especially the

less expensive and faster kinds. I'm sure there are photographic

ways of delivering resolution like that. I'm also sure that they're

neither easy nor cheap.

I can't compare my Canon's prints and Carol's Kodak prints here in

Contra for you because computer screens don't have that kind of resolution,

but it's striking how striking (metastriking?) the difference is.

There's a quantum jump between two and four megapixels that makes

me wonder if there will be a similar difference in perception between

four and six megapixel cameras, coupled with new printing technology

that we don't have yet. Four megapixels almost looks weird, as though

I have a space-warp window into another time and place. Will six or

more megapixels rendered in a high-resolution display technology be

so lifelike as to be disorienting? Either way, it looks to me like

a whole new art form, and it will be interesting to see what the professionals

do with it.

|

July

7, 2005: The Sovereignty of God July

7, 2005: The Sovereignty of God

I read a fair bit of theology, and there are times (as one who

cherishes the Catholic tradition) that I feel like a stranger in

my own country. One of these times happened recently while I was

reading a near-rant about the sovereignty of God. The expression

means just what you would expect: God is the ruler of the universe,

without exception. He is all-powerful and nothing escapes His notice.

To me this is a headscratcher. Making the point that God is all-powerful

is like saying that the dogcatcher catches dogs, or that magnets

attract iron filings. It's built into the definition: If God isn't

the all-powerful ruler of the universe, well, he's not God and we

need to keep looking.

I see discussions of the sovereignty of God on a regular basis,

and in my experience the vast majority of those discussions make

the point that God can do what he likes with us or anything else,

especially sending us to Hell, but also including striking dead

Uzzah, the poor goodhearted slob who tried to steady the Ark of

the Covenant (II Samuel 6:3-7), or having Elisha whistle up some

bears to eat a bunch of kids who were making fun of his baldness.

(II Kings 2: 23-25) (Because I understand doesn't mean that I approve,

heh.) Basically, as the term is most often used, "the sovereignty

of God" means "God can be a bastard if He wants to."

Well, sure. The ranters and I are in agreement on that one. God

can be anything He wants to. God can be an Elvis impersonator

or a Pizza Hut delivery boy, though I'm sure He has better things

to do with His time. A lot of people speak of the sovereignty of

God as a cover and an excuse for saying, "God can do what my

own mean-spirited, envious, vituperative self wants Him to do, which

is mostly cause pain to or consign to Hell the people I disapprove

of." (Some few use it as a way past problematic Scripture passages

like those cited above, and fewer still engage it in useful discussions

of the tension between divine power and human freedom.)

My point is this: Never, not even once, have I seen the

sovereignty of God invoked to support the possibility that God will

be kinder or more forgiving than our crippled understanding

of Him suggests. God can do anything he wants, which includes rehabilitating

even the worst of us, while giving us enough leash to be truly free

creatures on this Earth, and neither puppets nor pets. The sovereignty

of God is paradoxically the best support for both eternal damnation

and universalism (simultaneously!) that you could find.

As I mentioned earlier, inside the sock puppet of all these rants

on the sovereignty of God are two serious discussions, one about free

will and divine power, and the other the interpretation of Scripture.

I've thought some about both, but I'm about out of time this morning.

More in the next few days if I can squeeze it in.

|

July

6, 2005: Virtualizing the Internet Experience July

6, 2005: Virtualizing the Internet Experience

Sooner or later, you get stung: You navigate to a dicey Web site

and something ugly installs itself on your PC. Or you forget yourself

and open an attachment (or are fooled into opening it) and a trojan

starts marching on your registry. Ditto if you download something

from a Usenet newsgroup that contains a little extra ingredient.

Some of this malware is diabolically difficult to dislodge once

it's in place, and in many cases you have no choice but to wipe

your disk and reinstall.

There may be another way. My recent experience with virtual machine

software like Virtual

PC 2004 and VMWare

Workstation 5 suggests an interesting possibility: Create an

Internet suite (something like Mozilla) that contains its own virtualizer,

and thereby run all of your Internet software in a virtual machine.

I can envision a sort of launch bar floating on your screen, with

icons for Web, mail, Usenet, and IM. The launch bar is a window

into a virtual machine, with an additional icon to bring up a management

window, where you can take snapshots or delete them and configure

the overall system.

This could be done by starting with a copy of Linux and the Xen

hypervisor, stripping out the general GUI, and building a sort of

mini-OS that installs a "toehold" in the form of a Windows

service. When the suite is launched, the service loads the hypervisor

and creates a virtual machine for the suite apps to run in. You

hold a fully configured snapshot of the virtual machine in reserve

(it wouldn't have to be more than 100 MB in size, and probably much

less) and if the malware bites, you abandon the virtual machine

you were using and restore from the "clean" snapshot.

This is a little like using Norton Ghost or other brute-force restore

utilities, but with a crucial difference: Your underlying PC

is not affected in any way if malware strikes. This is true

for two reasons:

- The Internet suite apps are not running under Windows at all,

but under an embedded OS based on Linux. Malware intended for

Windows simply won't run, and because the hypervisor would not

run its apps as root, even Linux malware can't install itself.

- The isolation of the virtual machine from the underlying system

is extremely strong. I won't go so far as to say it can't

be broken (at least until our CPUs have built-in silicon support

for virtualization) but it will not be easy for malware to "get

out" of the virtual machine.

The weak link in any such system lies in how the virtualized Internet

suite shares files with the underlying host Windows installation.

That's why I suggest that a Windows service be running at all times:

Periodically, the service would "peek inside" the Internet

suite's virtual machine (this is easier than going the other way)

and sync whatever files the suite changes (mail, bookmarks, newsrc,

etc.) to copies in a directory on the Windows side. This would allow

other Windows apps to access the Internet data, and would also allow

easy restoration of the state of the Internet suite if the currently

running virtual instance had to be abandoned. The service could

invoke a malware detector on anything it syncs out from the virtual

system. (I would suggest not taking along email attachments or anything

even remotely executable.)

Just a goofy notion, heh. I now have 2 GB of RAM on my main system,

and will soon have 4. Installing a terabyte of hard disk is no longer

prohibitively expensive. (It's actually getting pretty cheap.) How

are we going to "spend" all of these riches? How about virtualizing

the Internet experience? Most of the misery in PC land is caused by

bad things that come in through your Net connection. We have the tools

to isolate Internet work from Windows itself. All we need is the will

to do it.

|

July

5, 2005: Odd Lots July

5, 2005: Odd Lots

- Pete Albrecht sent me a link to Heavens

Above, which will tell you when most of the brighter satellites

are visible in the sky from your location. This has helped me

to spot the ISS, which, while very bright, scoots across the sky

in a great hurry and can be easily missed. The only time I've

seen an Iridium flare was thanks to its guidance. First rate.

- Many years ago, I used to listen to avaiation chatter on the

AM aircraft band at 108-136 MHz. I don't even have a scanner anymore

(I sold it before we moved away from Arizona) but if you're interested

in that sort of thing, this

page will show you where aviation traffic happens.

- The S-Meter

page cited in the previous item is interesting in itself:

It allows you to hear radio signals through Windows Media Player.

Art Bell hosts one of the Web receivers, but it doesn't seem to

be related to most of the tinfoil hat stuff he presents on his

own show. It's fun (assuming you can stomach WMP) and I encourage

you to give it a try.

- There's an interesting conflict going on these days between

vendors trying to sell GPS re-radiators and the FCC, which doesn't

allow them in the US. Wal-Mart had been selling them and has now

stopped, and the FCC is pursuing any retailer attempting to sell

the devices, which are made in the Pacific Rim. (Would that the

Feds would go after spammers as enthusiastically as that!) GPS

re-radiators are niche-y but useful, if you have a GPS-based appliance

but don't have good access to the sky from the appliance itself.

They simply receive the GPS signal, amplify it a little, and re-broadcast

it on the same frequencies. People who own Meade

GPS-equipped telescopes sometimes find that the peculiarities

of an observing location (trees, buildings, whatever) attenuate

GPS signals past usefulness, so mounting a re-radiator under clear

sky can strengthen the signal that the scope itself receives.

Re-radiators are apparently legal in most places outside the US,

so if you want one, you're going to have to pack it home in your

luggage and pretend it's just another damned laptop parasite.

|

July

4, 2005: Applause July

4, 2005: Applause

Several of my friends have displayed some eyerolling at the line

in Episode III, in which Padme says: "That's the way democracy

ends, with applause." Yeah, like, well, who would applaud a

dictator?

Yeah, like, well, people whose democratic government has become

corrupt, incompetent, and dysfunctional. Hitler didn't come out

of nowhere. Germany was economically hobbled by the Treaty of Versailles,

and the Weimar Republic, created out of the ruins of WWI, was in

a state of near collapse when Hitler took power in 1933. The German

people wanted somebody, anybody, who could just get the country

functional again. The currency was worthless and people were starving.

They applauded him. Boy, did they applaud him. Like Mussolini, he

made the trains run on time, and got the country functional again.

Of course, he didn't stop there...

Even though we're nowhere near as bad off as the Weimar Republic

in 1933, there is still cause for concern. Like I've said many times,

freedom and democracy are loosely coupled, and not everyone values

all freedoms. (I'm astonished at the viciousness with which homeowners'

associations prosecute people who display the American flag, which

virtually all deed restrictions now prohibit.) Many people, perhaps

most people, would gladly give up the freedom to choose government

representatives if they felt it would allow them to keep their jobs

and some feeling of personal safety. We have entered a period in

American history when, for whatever reason, almost no one feels

secure, and that insecurity often has no grounding in reality. It's

all a little odd; while we seem to imagine an Islamic terrorist

behind every tree, it's the Supreme Court who's most likely to seize

our houses and hand them over to Donald Trump. The rich people who

build the nasty little gulags we call "gated communities"

are convinced that everyone except other rich people hate them and

would slit their throats in a second given the chance. People who

are losing their jobs in today's economic upheaval think illegal

immigrants are ruining the country. Liberals think conservative

Christians are trying to impose Biblical law on America. Conservative

Christians think liberals are trying to outlaw all public expression

of faith. Almost nobody expects to receive Social Security except

those who are already receiving it.

What's really happening is this: Everyone has a personal worldview,

and within each worldview is a smallish slice of insecurity. Trouble

is, those slices are all different. So even though the country is

working reasonably well in the aggregate, almost everyone has their

own little slice of creeping dread, and this slice is the lens through

which they see the future. Everybody is afraid.

As long as most people are making a living and paying the bills,

the worst that happens is acid indigestion. But if things start

getting really bad, the exaggerated terror people feel today will

become overwhelming, and even a modestly charismatic leader who

pushes the right set of buttons will be handed the keys to the country.

As bad as things were, people still believed in the future during

the Great Depression. Almost no one believes in it now. My great

fear for America is that we may lose democracy (and most of our

remaining freedoms) simply because we are afraid.

I happen to think things are still going reasonably well. On the other

hand, I keep one ear cocked for the sound of just a little too much

applause.

|

July

3, 2005: All My Outbound Mail Is Coming Back July

3, 2005: All My Outbound Mail Is Coming Back

I have some interesting things to write about, but I have a more

urgent issue this afternoon: Since some time yesterday morning,