|

|

|

|

July

31, 2006: Brides, Girlfriends, and Friends July

31, 2006: Brides, Girlfriends, and Friends

Thirty-seven

years ago tonight, I wandered into a church-basement function at

Immaculate Conception parish in the northwest corner of Chicago,

and a few hours later wandered out again, stunned at what I had

done: asked a beautiful girl out on a date, without anyone else's

intermediation. (All my previous dates had been setups.) After a

few weeks of doing unconventional things with Carol—we flew

a home-made D-stix tetrahedral kite together, looked at the stars

through my vent-pipe junkbox telescope, and attended a corn roast

at my family's summer home near Third Lake—I was stunned at

something else: She actually seemed to like me on my own merits,

nerdy and eccentric as I was. (The photo at left, from October 1969,

perfectly captures the Beauty and the Geek impression we must have

given people back in our first years together.) I had had modest

hopes of finding a girlfriend at that church basement function,

but I hit the jackpot: I found a friend instead. Thirty-seven

years ago tonight, I wandered into a church-basement function at

Immaculate Conception parish in the northwest corner of Chicago,

and a few hours later wandered out again, stunned at what I had

done: asked a beautiful girl out on a date, without anyone else's

intermediation. (All my previous dates had been setups.) After a

few weeks of doing unconventional things with Carol—we flew

a home-made D-stix tetrahedral kite together, looked at the stars

through my vent-pipe junkbox telescope, and attended a corn roast

at my family's summer home near Third Lake—I was stunned at

something else: She actually seemed to like me on my own merits,

nerdy and eccentric as I was. (The photo at left, from October 1969,

perfectly captures the Beauty and the Geek impression we must have

given people back in our first years together.) I had had modest

hopes of finding a girlfriend at that church basement function,

but I hit the jackpot: I found a friend instead.

More and more I hear guys say "my bride" instead of "my

wife." Maybe this is because "wife" has been deprecated

as a reserved word, which is one of my main gripes with our feminist

fringe. I think perhaps that the guys understand this and are reaching

a little further for a term of honor, and "bride" is certainly

that. Carol was and always will be my bride.

Alas, "bride" is not enough. I know of a number of marriages

in which bride and groom can barely stand one another. A "girlfriend"

these days usually means a woman you're sleeping with. (The irony

of "lover" as a word for a person one has sex with irrespective

of the presence of any real love has always made me grimace.) English

has many words for many odd and highly specific things—"cerate"

means "to coat with wax"—but I have yet to find the

word that combines "bride," "girlfriend," and

"friend" into a single term of honor. I suppose it's difficult

to be a spouse, lover, and friend all at the same time; more difficult,

fersure, than coating something with wax. That Carol and I have managed

it for so many years is a point of intense pride with me, and if I

can't have a word, so be it. The reality speaks for itself.

|

July

30, 2006: Odd Notes on Chicagoland July

30, 2006: Odd Notes on Chicagoland

Carol and I are in Niles, Illinois (adjoining Chicago on the north

end) for a while, helping her mom out with a few things. Although

we both grew up here (she in the very house we're staying in) we

had forgotten a few things:

- It gets hot here—hot and smotheringly damp. I don't

know how they breathe this stuff. It was 100+ degrees here today,

with humidity you could cut with a hacksaw. I've been hiding in

the basement a lot.

- The soil is black. Very black. We took "black dirt"

for granted as kids, but everywhere else I've lived the soil has

run from brown to red. Digging in the yard was startling.

- The air raid sirens are still tested at 10:30 AM every Tuesday,

as they did when we were kids. I always thought that this was

a nationwide phenomenon, but nowhere else we've lived performs

such tests. Fort Carson sounds off a similar siren every time

anybody at the base spots a thunderhead, with a Lost In Space

robot-style voice slowly announcing "Severe...thunderstorm...warning.

Severe...thunderstorm...warning..." but tests are rare and

not at any specified time.

- We stopped for coffee at a White Hen Pantry in Crystal Lake

the other day, and they had a fresh produce rack with apples,

sweet red peppers, string beans, and sweet corn. Yet another reason

I consider White Hen the best convenience store in history. Their

coffee is spectacularly good, and they often have flavors you

don't see at other similar retailers. As best I can tell, White

Hen is a Chicago metro phenom. We've not seen them anywhere else.

Try their coffee if you haven't already.

- There is a style of two-sided poured concrete washtub in the

basement of virtually every Chicago-area house built from WWII

until 1970 or so that I've never seen anywhere else. The one we

had on Clarence Avenue in Chicago's northwest corner actually

had a little aluminum washboard embedded in the side of one of

the tubs. Having two tubs can be extremely useful, in that one

can be used to wash dogs, and the other to rinse them, especially

if the wash contains flea dip. Our dogs Hank and Smoker got this

treatment more than once, down in the basement in the house where

I grew up.

- The cicadas are going nuts this year. In the afternoon

they've been deafening, and I don't recall hearing any at all

in Colorado Springs so far. We were walking QBit down Main St.

the other day, when he happened upon an adult cicada sitting on

the sidewalk. The adults don't bite (I'm not sure they even have

mouths to bite with) but when poked they buzz startlingly. QBit

nosed it very lightly, wondering if it might be tasty, and when

the insect sounded off he jumped two feet straight up.

- Everywhere else we've lived, "family restaurants"

are dominated by monster chains like Denny's, Village Inn, and

so on. Here, there are any number of excellent one-off family

eateries, all (for some reason) owned by Greek guys. Kappy's,

Omega, and Seven Brothers are the ones we visit, but in driving

around the area I see them all over the place. The menus are unprediuctable

and a lot more varied (Kappy's sells gyros and reuben sandwiches

side by side) and I often wish some Greeks would move to Colorado

and open places like this.

|

July

29, 2006: Artisanal Cheese July

29, 2006: Artisanal Cheese

When we were up in Wisconsin a few days ago, my cousins Rose and

Al took us around the old turf (my mother was from Wisconsin and

many of my cousins still live there) to show us, mostly, that nothing

was the way it was when we had spent time there in the late 1950s

and 1960s. We went past the old cheese factory, to which my dairy

farmer uncle had sold milk for many years. The factory is now a

quirky house and handsome in its way, though I wonder how it smells

inside on a hot afternoon. Certainly I'd prefer that it be a house

rather than a teardown to make way for a generic McMansion—but

in truth, I wish it were still a cheese factory.

Dairy farming in Wisconsin seems to be in decline. (I don't have

any hard numbers, but we didn't see many cows in fields along the

roads we traveled.) So I was pleased to read in the July 28th issue

of The Chicago Reader that Wisconsin is still ground zero

for cheese production, at 2.4 billion pounds sold last year, tops

in the country. California is right behind at 2 billion pounds,

though much of what they produce is the ugly orange "American"

cheese that I haven't willingly eaten for almost forty years.

Wisconsin apparently saw the threat from California, and has been

moving aggressively into "artisanal" cheese. (This means

cheese made by artisans,

though I didn't know "artisanal" was a word. Shades of

"liaise.") A few weeks ago Wisconsin cheeses swept the

American Cheese Society competition, held in Portland Oregon for

reasons unexplained. Blue ribbons were won by Wisconsin for things

like "best blue-mold cheese made from cow's milk" and

"best cheddar aged longer than 49 months."

I never liked cheese that much, mostly because all the cheese we

ever had at our house was that horrible American stuff, and whatever

artificially colored imitation cheese-flavored goop substitute it

was that we put on macaroni and called dinner. (I grew up poor,

and I think I've had enough mac-and-cheese and toasted cheese sandwiches

for one lifetime, thanks.) I actually learned to like cheese through

Carol, who considers it her favorite food category. I've found that

a couple of slices of a good strong Romano cheese mid-afternoon

keeps me from munching potato chips, and that after a couple of

slices, I stop. (It doesn't work that way with potato chips,

heh.)

So it's good to see that Wisconsin's designer cheese industry is

booming. Good things generally come from small producers, and there

are 1,225 licensed cheese producers in Wisconsin, almost all of

them family businesses. (That number doesn't include hobby cheesemakers,

of whom there are many.) Not all of them make money, but the artisanal

cheese field is relatively new, and I suspect that there are a lot

of other people out there like me, who would eat good cheese if

they simply knew it existed and could find it.

Alas, quirky products are often local in nature, and I don't live

anywhere near Wisconsin anymore. I have come to like quirky wines,

and have found more among Colorado wines than I can deal with; in

a sense, local wines, to compete with mass-market tank car wines

from California, almost have to be quirky. The same is likely

true of cheese, and if I can find a source for odd Wisconsin cheese

in the Springs, I will be a very happy guy.

In the meantime, you folks here in Chicago should see what interesting

things have come down I-94 from American's Dairyland, and enjoy your

privileged position as the Closest Big City to the World's Best Cheese.

|

July

28, 2006: Combating "Government Theater" July

28, 2006: Combating "Government Theater"

Back in Chicago. And mon dieu, Chicago politics. I catch

flack when I say that politicians are liars, morons, or nasty people,

and maybe the objectors are right. Maybe it's not the people. Maybe

it's the system. The core truth is that politics as we know it today

is not about furthering the common good, but about having power

and keeping a government job. As long as politicians can look

like they're doing what the people want (or say what the people

want to hear, even if it's all lies) the people will keep electing

them. Call it "government theater." It's what we have,

and it's not doing us any good.

Maybe there's another way. Maybe democracy shouldn't be about electing

people. Maybe democracy should be about setting targets.

Imagine a system of democracy that works a little like a simulation

game, in which lawmakers may keep their offices indefinitely as

long as several key measurable societal parameters are all

kept within democratically set boundaries. The people choose the

target values via regular referenda, and the politicians are charged

with meeting the targets to keep their jobs. In other words, if

you're on the city council, you can stay on the city council as

long as budgets remain balanced, taxes do not rise, unemployment

is kept under 3%, school scores are at the national average or above,

and crime rates are at the national average or below. Lose any parameter,

and we get a special election that chooses a whole new city council

and mayor. Like Sim City without the sim. (Oh, and once you're out,

your political career is over.)

Figuring out how to set numeric targets via referenda is an interesting

problem, but not an insurmountable one.

The idea here is that politicians can say whatever they want to get

elected, but getting elected is only the beginning. Elected lawmakers

would have to produce the results that the people want, or retire.

Politicians will of course say that this is impossible, but it's unwise

to believe anything politicians say. We won't know until we try.

|

July

27, 2006: Ghost Towns July

27, 2006: Ghost Towns

Carol, Rose, Al, and I did a little wandering before we had to

head back. We drove through several of the tiny towns near Green

Bay where we had all spent time as kids. Some, like Pulaski, seemed

to be booming. Others, like Krakow (above), the tiny hamlet just

down the road from my uncle's farm, were rapidly becoming ghost

towns. The little grocery story and the ice cream shop were gone,

though there's still a bar. Remarkably, St. Casimir's, the little

Roman Catholic church we always went to on Sunday (with the sermon

said first in Polish and then a second time in English!) is still

there and still active, set amidst beautifully maintained grounds.

By contrast, the 1928 public grade school, long shuttered, is rapidly

being absorbed by the weeds.

Interestingly, we did not see churches being turned

into bars, or organic grocery stores, or eccentric houses. The Polish-American

culture in northern Wisconsin is still strong. The cathedral in

Pulaski is enormous and full on Sundays. There's even an Old Catholic

mission church forming in Pulaski: The Polish National Catholic

Church (an Old Catholic jurisdiction with married priests and bishops)

bought an old Lutheran church and are rehabbing it.

I fought back a certain annoyance at Krakow's decline by reminding

myself that this is nothing new. Towns vanish all the time for reasons

that we may never fully understand. Towns, like farms, can consolidate,

especially with better roads and cars for anyone who wants one.

If there's more choice in Pulaski when you need to go shopping,

why stop in Krakow? I suspect that Krakow was very much the town

of very small farmers along narrow, twisting county tracks like

Gohr Road, and most of them are gone now.

I take some comfort in seeing that Krakow may be an exception.

Most of the towns we passed through in Wisconsin seemed remarkably

vibrant, with plenty of local retail and new cars in driveways.

Fewer people seem to be employed in farming, but more people are

employed in other industries, stores, and infrastructure jobs catering

to people who build houses in the far outlying towns and commute

into Green Bay.

Maybe some are even telecommiting to IT jobs in Silicon Valley, hacking

C# code between trips out to the barn to slop the hogs. For the price

of a condo in Cupertino, you can have a farm in northern Wisconsin.

And hey, if they lay you off, you still can have eggs for breakfast

every morning, and all the pork you can stand!

|

July

26, 2006: Diversity in Small Farming July

26, 2006: Diversity in Small Farming

We went visiting today, and saw three of my cousins who are Uncle

Joey's kids, two of whom I hadn't seen since I was in high school.

Aunt Della is still alive and we visited with her as well.

It does come as a shock to see cousins as middle-aged when the

last time you saw them they were fourteen. We drove past the place

where the old farm used to be, on Gohr road near Krakow, almost

directly across from the huge Gohr family farm that was the road's

namesake. The buildings were torn down decades ago and the acreage

sold to adjoining farms. (Even the silos had been razed.) I recognized

a couple of the big trees that once held big tire swings.

(Who needs a Tilt-a-Whirl when your cousin Tony will spin the tire

with you in the middle of it?) The rest was simply gone.

Easily the most interesting visit of the day was with my cousin

John Pryes. He's only two months younger than me, and we did a lot

of exploring in the back fields and woods on and near his family's

property when we were kids and young teens. He went back to farming

some years back after a long absense, and he works a small farm

near Pulaski with his daughter and ten-year-old granddaughter. Both

he and his daughter work day jobs; he as an IT guy at a hospital

in Appleton and she at a yacht factory in Pulaski.

Nonetheless,

they have three small barns, a one-acre garden with everything from

sweet peas to Concord grapes, some acreage in various animal feed

crops, and an amazing diversity of animals. They have several beef

cattle, including one bull. They have two adult pigs and (currently)

eight five-week-old piglets. They have a large flock of what to

me were enormous chickens. They have several lop-eared rabbits.

They also have four or five sheep and about ten goats, along with

two dogs and an unknown number of cats. QBit was a little apprehensive,

sniffing noses through the fencing with creatures many times his

size, and one of John's cats kept trying to play with him, which

definitely took him aback. (My sister's cats are terrified of him.) Nonetheless,

they have three small barns, a one-acre garden with everything from

sweet peas to Concord grapes, some acreage in various animal feed

crops, and an amazing diversity of animals. They have several beef

cattle, including one bull. They have two adult pigs and (currently)

eight five-week-old piglets. They have a large flock of what to

me were enormous chickens. They have several lop-eared rabbits.

They also have four or five sheep and about ten goats, along with

two dogs and an unknown number of cats. QBit was a little apprehensive,

sniffing noses through the fencing with creatures many times his

size, and one of John's cats kept trying to play with him, which

definitely took him aback. (My sister's cats are terrified of him.)

The economics of a farm like this are complex. They shear the sheep

themselves and sell the wool. The breed of goats they raise are

meat animals and do not give good milk; they sell them to locals

either to augment their own herds or to slaughter. The cattle are

beef cattle, and they sell calves to other farmers. The same with

the pigs: They sell piglets to other farmers to keep genetic diversity

up, and mostly grown pigs as meat. Their chickens lay about a dozen

and a half eggs a day, which certainly keeps the family in eggs,

but isn't really enough to make much money on, though they barter

eggs for small quantities of other things they need.

And as John said with his same old wry grin, they always have as

much pork as they can stand.

Like all small farmers (and his father before him) John is an espert

Yankee mechanic, and he has two tractors in one of his barns that

have been in continuous service since WWII. He rents unneeded space

in his barns to his city friends who need a place to put their boats

or classic car projects. It's hardly the high life, but John seems

happy and healthy. He has a volleyball court next to his house and

makes time to use it. Lord knows he gets his exercise, and were it

not for the gray hair he would look ten years younger than he is.

It's not a life I could ever embrace, but I admire him for it, and

it was good to finally see him again after all these years.

|

July

25, 2006: Barns and Back Roads July

25, 2006: Barns and Back Roads

Wisconsin

is sacred ground for me. My mother was born here, and we visited

my dairy farmer uncle frequently when we were kids. It was the first

place I ever actually touched animals that weren't dogs, and drank

water that came out of a well. It was where I learned that peas

fresh from the pods they grew in taste way different than peas in

a can. It was where I discovered (ouch!) that cucumbers have thorns.

Coming from a claustrophobic city neighborhood as I did (the house

I grew up in was on a lot only 30 feet wide!) it just seemed like

Wisconsin went on forever. Wisconsin

is sacred ground for me. My mother was born here, and we visited

my dairy farmer uncle frequently when we were kids. It was the first

place I ever actually touched animals that weren't dogs, and drank

water that came out of a well. It was where I learned that peas

fresh from the pods they grew in taste way different than peas in

a can. It was where I discovered (ouch!) that cucumbers have thorns.

Coming from a claustrophobic city neighborhood as I did (the house

I grew up in was on a lot only 30 feet wide!) it just seemed like

Wisconsin went on forever.

Carol and I decided not to take the Interstate up to Green Bay,

or even US Highway 41, which might as well be an Interstate. Instead,

we took ordinary two-lane roads, and willingly went through small

towns instead of doing anything possible to avoid them. We didn't

steer in the direction of any tourist attractions. We just drove,

and paid attention to what went by outside the Sprinter Legend's

very big windows.

Farms, of course—and an enormous amount of green stuff, both

wild and cultivated. I've lived in dry places for almost twenty

years now, and by comparison, Wisconsin seemed like a jungle. I

expected to see a lot of cows, but in fact we saw a lot more corn

than cows. All I could think of was ethanol—or perhaps high-fructose

corn syrup. One wonders where all the milk comes from now; my guess

is California.

Dairy farming was not a big-money business even when I was a kid.

Uncle Joey had forty or fifty cows and he still had to work a second

job at a local pickle factory to make ends meet, and from what I

remember, he made about as much money selling cucumbers to local

pickle producers as he did selling milk, and he sold the farm in

the early 1970s as his children grew up and left home.

Small commodity farming as a viable business model is probably

extinct. One thing that struck me as we drove the winding roads

in rural Wisconsin was the number of concrete silos standing in

the thick of cultivated fields without any barns or other buildings

nearby. What's clearly happened is that small farms have been merged

with bigger ones, and the rickety, WW-I era buildings torn down

and sold for their weathered wood. Knocking down concrete silos

is difficult and expensive, however, so the silos are left to stand,

empty and often capless, at the edges of fields.

The farms that remain are huge, compared to my poor uncle's little

place. We would often see two or three modern barns side by side,

with bright metal silos and enormous pieces of equipment painted

John Deere green. It's big business now, and without economies of

scale, I don't think that small farms can survive.

We had a quiet dinner this evening at a restaurant along Duck Creek

near Howard with my cousin Rose and her childhood sweetheart Al.

They knew one another as young teens fifty years ago, and then left

Wisconsin to find their own lives elsewhere, complete with spouses

and kids. Now, both widowed for some years, they've returned to

Wisconsin and found one another. We toasted to steadfast love. Carol

and I know that feeling in one another; it was good to see it in

other people around us.

Tomorrow we look up some of the cousins, and cruise around the old

territory a little.

|

July

24, 2006: Off to Wisconsin! July

24, 2006: Off to Wisconsin!

Given that we'll be here in the midwest for another

week or two, Carol and I decided to take a break and embark on a

trip-within-a-trip, to drive up to Green Bay. I have 21 first cousins

on my mother's side, of whom more than half live in Wisconsin, nearly

all within a few miles of Green Bay, and many of which I haven't

seen in more than thirty years.

So we rented another small RV and aimed its nose north this morning.

The RV is from Great West Vans, a Canadian company that specializes

in the small Class B van conversion RVs. We

rented a Class B back in June and took it to Breckenridge, and

because an RV dealer in the northwest burbs rents Class Bs, it was

a natural. The Great West Sprinter Legend is interesting because

it's basically a conversion of the Dodge Sprinter van, which was

designed by Daimler in Germany and uses a 5-cylinder (!) turbo-charged

Diesel engine from Mercedes-Benz.

It was designed as a delivery van for use in Europe, and its narrow

body probably works better on European roads. The narrow body means

that there's not a lot of elbow room inside, and although it's tall

and has plenty of headroom, the two small beds in back are probably

about what the swabbies get in the belly of an aircraft carrier.

The bathroom is basically identical to the bathroom in the Pleasureway

Class B we took to Breckenridge, with a very small shower and a

pull-out sink. We don't intend to try the shower. (I dare you to

shower well in a vehicle with a five-gallon hot water tank and two

and a half square feet of space to stand in!) The toilet is a sailboat

toilet, and although it's better than nothing, it's not a lot

better than nothing. The bathroom door kept opening on the trip

up, and I had to wedge it with the cooler to keep it from flapping

around.

For

something this small, the Sprinter Legend has a reasonable amount

of storage space, distributed among a lot of tiny cabinets and a

decent-sized "trunk" under the beds. We had no trouble

fitting two suitcases, a storage bin, and a cooler in the vehicle,

along with my very fat briefcase and a lot of other odds and ends.

We did not rent the flat-panel TV (that was $50 extra) but there

is a TV antenna on the roof, and a built-in CD/DVD player. The refrigerator

can run on either propane or 110VAC, and did a very good job keeping

sodas, milk, cheese, bratwurst, and yogurt cold. We're keeeping

ice in the cooler for additional sodas and QBit's raw dog food that

he seems to love more than life itself. For

something this small, the Sprinter Legend has a reasonable amount

of storage space, distributed among a lot of tiny cabinets and a

decent-sized "trunk" under the beds. We had no trouble

fitting two suitcases, a storage bin, and a cooler in the vehicle,

along with my very fat briefcase and a lot of other odds and ends.

We did not rent the flat-panel TV (that was $50 extra) but there

is a TV antenna on the roof, and a built-in CD/DVD player. The refrigerator

can run on either propane or 110VAC, and did a very good job keeping

sodas, milk, cheese, bratwurst, and yogurt cold. We're keeeping

ice in the cooler for additional sodas and QBit's raw dog food that

he seems to love more than life itself.

A two-burner propane stove and a microwave oven round out the kitchen

equipment. There's a Diesel generator and an extremely powerful

interior air conditioner that got the inside of the coach so cold

that water began condensing out on the leather seats.

I doubt that Carol and I would ever buy one of these (it's just

too small to sleep comfortably in) but it was certainly fun to scoot

through small farm towns in it. The Diesel powerplant does an amazing

job on only five cylinders. The vehicle has a lot of punch, can

cruise at 80 MPH, and gets 19-22 MPG.

We stopped at a KOA campground near Fon Du Lac a few hours ago, and

because they don't have Wi-Fi, I'm not entirely sure when this will

get posted. Bear with us.

|

July

23, 2006: Sagas and Destinies July

23, 2006: Sagas and Destinies

A couple of people wrote to ask me to clarify what I meant in my

July 20, 2006 entry, where I said that

sagas (by which I mean a background universe or situation against

which stories are written) should have destinies. My Drumlins stories

are part of something I informally call the Gaeans Saga, which includes

The Cunning Blood and its possible sequels as well.

Stories are actually about change, in a character, a situation,

or (ideally) both. So it seems to me that story backgrounds should

also change over time, just as our own history does, and ultimately

resolve issues pointed to by the stories in the saga. E. C. Tubb's

mostly forgotten Dumarest of Terra stories were a saga, in which

Dumarest searches for the lost Earth, and in each novel he finds

clues and gets a little closer. (I didn't read them all, but I think

that's a fair statement of what the saga's about.) We can hope that

the Harry Potter books will eventually say something not only about

the characters in the stories but about the relationship of magic

to humanity as a whole (muggles and all) and what the hell it all

means.

The Gaeans Saga contains a number of interesting larger issues,

a few of which are these:

- Who are the Gaeans?

- What are they up to?

- How did they arrange the universe as they did?

- And why?

- Where do the uploaded human minds go? (e.g., Jamie Eigen in

The Cunning Blood)

- What were the Thingmakers really created to do?

- What is the relationship of the Gaeans to human beings?

(There are more. I've only begun to explore the place myself.)

To come to a satisfying conclusion, all of these questions have

to be answered. And once they're answered, there's a lot less richness

to any stories you might tell within the saga. The saga has a destiny.

Some people like mystery to remain mystery, and may object to answering

questions concerning mysteries. It's like asking what the restaurants

are like in Tolkien's Uttermost West: Valinor is not about restaurants,

and is really an elf thing, closed to mankind both physically and

conceptually. That's true for mysteries that ultimately don't concern

humanity (or humanity once it's transcended its humanness) but for

ordinary human beings, mysteries were made to be solved. Stories

and sagas that pose human mysteries but do not solve them (or do

not pose them in the first place) are not as satisfying as sagas

in which lives and histories change, and in doing so provide insights

into the human condition.

That's what I meant, and that's what I intend to do in the Gaeans

Saga. It has already started. It will go somewhere. It will reach

a climax. And it will stop.

After that, well, I'll just invent another saga. That's what writers

do.

|

July

22, 2006: Review: Monster House...in 3-D! July

22, 2006: Review: Monster House...in 3-D!

We're in Chicago for a bit, and Carol's been here now for over

a week, cleaning her mom's house with her sister. After a week of

nonstop elbow greasing, it was time for a break, and we decided

to go see Monster House. Our first issue was simply finding

a theater. With the single exception of the Pickwick in Park Ridge,

all the closest theaters we used to go to here as kids were gone—in

many cases, long gone. The elegant Gateway at Milwaukee and Lawrence

(where I remember seeing The Ten Commandments as a very small

child) is now a Polish cultural center. The Morton Grove is now

a shoe store. The theater up at Golf Mill is gone, as is the Lawrencewood

in the shopping gully my father used to call Skunk Hollow, where

I took Carol to many movies when we were teens. We had to haul east

on Touhy to some nameless multiplex to find a screen on which Monster

House was playing.

And then when we found a showing at the right time, we discovered

that the showing was in 3-D. I was nervous: Carol already had a

headache, and my experience with 3-D films was limited to two items

going on thirty five or forty years ago. One was a completely awful

Japanese trash-Tokyo monster flick, and the other was a sexploitation

thing I saw in college (about stewardesses?) of which all I remember

is instinctively ducking down in my seat as the heroine's outsized

breasts swung out over the audience. Ahh, the Seventies...

So it was with some trepidation that we bought our 3-D glasses

and took our seats. And I'll sum up this way: The movie gets three

stars, and the 3-D technology five stars. No more green and red

plastic film in cardboard goggles. The new 3-D technology is based

on polarizing filters, and while it reduces the overall brightness

of the film, the 3-D effect was absolutely dazzling.

The movie was modestly entertaining, but not in a league with Shrek,

Monsters, Inc. or A Bug's Life. There were script

problems. I kept wanting to yell at the screen: You can't compensate

for crappy writing with dazzling animation! What we really have

here is a clever half-hour short padded out to 90 minutes. The story

is simple: Two twelve-ish boys living across the street from a seriously

haunted house fail to convince the local adults that the house is

swallowing dogs, brain-damaged punker boyfriends of the babysitter,

and any toy that any unfortunate kid lands on the ravenous front

lawn. When a cute girl selling Halloween candy door-to-door to help

her exclusive prep school gets grabbed by the house, the boys rescue

her, and the three of them mount an offensive that eventually gets

things straightened out.

Alas, many of the film's best moments have nothing to do with the

haunted house. Jenny the prep school girl engages in a fiendishly

funny negotiation with the boys' babysitter, who had been tossed

out of the same prep school years earlier. The babysitter's boyfriend

Bones is as brilliant a sendup of punk pop culture as anything I've

ever seen. DJ's father is an orthodontist who is constantly schlepping

around huge models of teeth and monster toothbrushes.

I have one serious problem with the film, though telling you about

it borders on a spoiler: I do not like movies that exploit

the problems of fat people, especially fat women. The Hitchcockian

backstory involving a WWII demolitions expert and a circus fat lady

was painful to watch, and I'm sure was completely lost on the core

audience.

The climax, in which the house literally uproots itself and starts

walking down the street like a Japanese Tokyoivore, was a lot of

fun, and the whole thing took me back a little bit to my geeky 12s,

when I would oscillate between lusting after the girl down the street

and playing with telescopes and imagining vast glocal conspiracies.

None of the voices were by superstars, but all were very well done.

The animation was an interesting compromise between the creepy Polar

Express and crappy flat anime: Although the animators used motion

capture technology on young live actors, they stretched out the

bodies and exaggerated facial expressions enough so that we didn't

fall into the Uncanny Valley.

The 3-D effects were a delightful surprise. The damned house was stomping

and chomping around right in the air in front of us, and I giggled

like a kid, which proved to me that Monster House indeed achieved

its core mission. Recommended.

|

July

21, 2006: When Books Die July

21, 2006: When Books Die

I flew in from Chicago yesterday, and spent four hours

waiting out weather delays at O'Hare before I could even get on

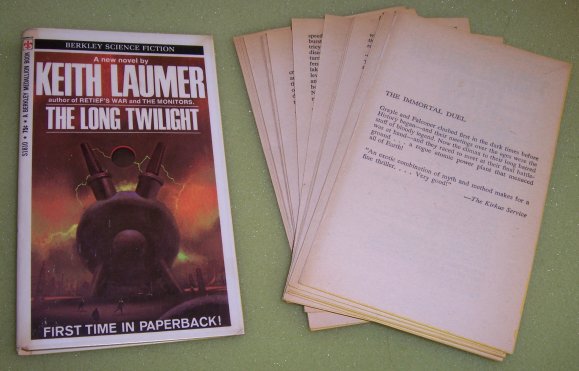

a plane. As always, I had a number of books in my bag, including

one that I don't think I've read in over thirty years: Keith Laumer's

1969 novel The Long Twilight. Laumer is special to me: More

than any other single writer, it was he who I imitated when I was

in high school and beginning to write SF. I discovered Laumer in

1966 with The Great Time Machine Hoax, and read him voraciously

until his work petered out in the 70s. He was a topic of much conversation

at our geek lunch table, and I studied him intensely when I was

trying to figure out how to write a good action sequence.

Although Laumer is now remembered mostly for his lighthearted Retief

stories, The Long Twilight is typical of his serious SF dramas:

Two immortal warriors from the dying interstellar empire of Ysar

are marooned on a backward planet (Earth) about our year 1000. Although

initially they are friends and colleagues, one comes to believe

(falsely) that the other has murdered his family, and so there arises

a thousand-year feud that comes to a climax only when those primitive

Earth barbarians build a wireless distribution nuclear power plant

(in the 1980s) that provides power to their technological body enhancements,

as well as their enimgmatic starship Xix, buried in the wilds of

northern Minnesota.

The Long Twilight is not Laumer's best work. It's

a novella padded out to publishable book length. I couldn't see

this when I was 17, but now, having read countless novels and written

several of my own (of which only one has seen print) I can see the

seams, the bad welds, and the glued-on bulk. There's a completely

untenable (and mostly unnecessary) subplot involving the US Army

trying to attack and turn off the power plant, which Xix is secretly

keeping running using technologies that smell perilously like occult

magick. There's a forced and completely unnecessary romantic subplot.

I guess for the hero to get the girl, there has to be a girl, though

in this case the hero seems completely uninterested in the girl

until the omniscient author forces her into Lokrien's arms on the

last page.

Doesn't matter; I recall my heart pounding as a kid while I read

the action scenes. I recall typing some of his paragraphs into my

1918 Underwood mill just to see what publishable SF would look like

on the platen in front of me. (It looked frighteningly like my own

Laumer-inspired adventures, a thrill that kept me going until I

sold my first SF yarn at age 22.) I'd really like to keep the book

on my shelf, as a lesson in how not to spin a plot, as much as for

the bad story's nostalgia value.

Alas, there's a problem: The gum that holds the pages together

and the pages to the cover dried out and cracked as soon as I opened

the book. Each time I turned a page, the page pulled loose of what

was left of the crumbling binding gum and came free in my hand.

By the time I had finished the novel, I had a stack of entirely

separate yellowed pages and the cover, which still looks great because

I covered it in Con*Tact plastic back in 1969.

I'm going to have to go looking for a hardcover copy with a sewn

binding. I'd also like to have an ebook version, but I don't know

that I want it badly enough to scan and OCR 220 fragile pulp pages

and knit them together into a PDF. I'd certainly buy an ebook if

one were available.

There is an enormous amount of money lying on the floor in the form

of third-shelf books that only a few crazies (like me) and completists

might want. Maybe the answer is a sort of compulsory licensing for

books over a certain age (25 years?) in which anyone may republish

the books as long as they pay the rightsholders (Keith Laumer is now

dead) 10% of the sale price. Big Media doesn't understand that they

would make more money by loosening the chains on older and less popular

titles, and I doubt that they ever will understand, because as I've

said here on several occasions, they're really not in it for money.

They're in it for the control. (Right Men only want money as

long as they completely control the process that generates

it.) Short of a bullet to the head, what will it take to change their

minds?

|

July

20, 2006: Sharing a World July

20, 2006: Sharing a World

Over the past year, some writer friends and I have had some success

creating a writers' workshop here, and in several meetings we've

run about a dozen stories through the mill. Terry Blair, who writes

literary fiction of the type you'd see in The New Yorker,

made a suggestion that surprised me: That we should mount a workshop

project in which we all write a story set in a shared world. And

she wanted the world to be my Drumlins world, in which "Drumlin

Boiler" (Asimov's, April 2002) was set.

I had already been discussing this with George Ewing, and had begun

writing a backgrounder on the Drumlins universe so that he could

explore some concepts. The idea forced me to think hard about how

an imaginal world can be shared effectively. It's been tried any

number of times, and I've not been completely happy in any instance.

Harlan Ellison's Medea shared world was an utter botch. Janet

Morris' Heroes in Hell worked better as a shared world, but

the underlying concept didn't hang together very well, and a lot

of the stories quickly descended to soap opera. (A few, however,

were cracklin' good adventure.) The first few Man-Kzin Wars

stories were well-done (especially Dean Ing's), but the material

got repetitive after awhile—probably because the idea of a

war between two species is a little narrow. Perhaps the best shared

world that I've seen so far is Will Shetterly's Liavek, which

featured an all-star cast of writers and some fairly clever concepts,

though it was a sort of Arabian nights fantasy that is a tough sell

for a hard SF guy like me. All of these projects were creatures

of the 1980s, and there may be newer and better examples. I'm looking

around for good shared worlds to learn from, and suggestions are

welcome, especially if they're hard SF rather than fantasy.

I have a strategy in mind, and I figure I'll fine-tune it as we

go. Here are some notes:

- The shared background has to be worked out in enough detail

to allow a common vision of what is to take place here. I currently

have 8,000 words in the backgrounder, with more to come. As our

workshoppers ask questions about how things work on Drumland,

I've been adding more material to the backgrounder. This includes

specs of the planet, how the society there operates, movers and

shakers within that society, and even maps of towns and seacoasts.

And of course, there is the shared mystery of the Thingmakers,

and the 1.54 X 10E77 things that they can manufacture. I'm not

quite ready to release it yet, but at some point I will make the

backgrounder document freely available.

- Writers contributing to a shared world have to show their hands

early and often. Internal consistency is crucial. (This is where

the Medea world failed.) Contradictions among writers'

depiction of background elements and storylines confuse readers

and make the whole thing a headache to read. We can strive to

surprise our readers, but we can't try to surprise one another.

Writers contributing have to share details of their plots and

characters not only with me, but with all the other contributors,

so that we can resolve the inevitable collisions by consensus

and not always be tripping on one another's egos. (It may help

that none of us are famous SF writers.)

- A shared world should have a destiny. It shouldn't just be a

sitcom, or an episodic adventure. I'm going to try and guide the

creative process such that all the stories point gently toward

where the whole saga is going. And at some point, I'm going to

say, "It's done."

None of us have ever done anything like this before, and I admit that

it may not work. We're only getting started, but things are underway.

I have about a third of "Drumlin Wheel" finished, and I'm

working with Terry on her concept, which is coming along well and

is almost certainly something none of the rest of us could have done.

(I'm often delighted with what non-SF writers produce. The two Georges

are working on their concepts. I may invite a couple of other non-local

writers to consider a contribution. I'll let you know what happens

in this space.

|

July

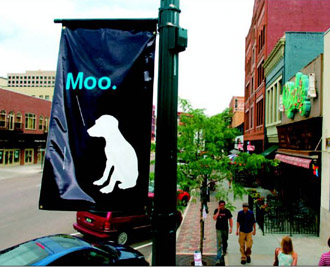

19, 2006: The Dog That Goes "Moo!" July

19, 2006: The Dog That Goes "Moo!"

I

love this city for many reasons, but when I announced our move here,

a number of our more liberal friends were very unhappy. Beyond

a slightly creaky Cold War assumption that NORAD (from whose iron

door I am less than one mile) is on the Russians' first strike list,

the objection they raise has never bothered me that much: Focus

on the Family is there. I doubt that any organization is anywhere

near as abhorred on the left as FOTF, whose massive complex lies

about fourteen miles north of us, at the other extreme of the city. I

love this city for many reasons, but when I announced our move here,

a number of our more liberal friends were very unhappy. Beyond

a slightly creaky Cold War assumption that NORAD (from whose iron

door I am less than one mile) is on the Russians' first strike list,

the objection they raise has never bothered me that much: Focus

on the Family is there. I doubt that any organization is anywhere

near as abhorred on the left as FOTF, whose massive complex lies

about fourteen miles north of us, at the other extreme of the city.

I am increasingly uncomfortable with FOTF's brand of Evangelicalism

(and there's a separate story in this that I'm working up the nerve

to tell) but mostly I cordially ignore them, as I cordially ignore

most individuals and groups with whom I differ but who are unlikely

to hit me on the head and run off with my wallet. Ideology is not

my thing. On the other hand, Colorado Springs has become so unshakably

linked with the Christian Right that I have a suspicion many tech

startups are unwilling to locate here or expand here. I say that

because it comes up again and again as I chat over Skype or email

with people in tech: "Oh, you're in Colorado Springs. Christian

country. Focus is there." Everybody seems to know, and the

unspoken objection is deafening.

The tension between Focus and the culture that it loathes erupts

now and then, and we're currently in the thick of another round

here. For several weeks now, an advocacy group called Public Interest

has been funding TV commercials and banners on street lights featuring

a peculiar icon: A

dog saying "Moo!" in a speech balloon. Norman, the

dog, was born different. He doesn't bark. He moos. He didn't choose

to moo. That's just the way he is.

It's a clever, nonconfrontational,

slightly light-hearted campaign to get people talking about

why gays and lesbians are what they are. Focus on the Family, however,

is incensed. They see targets on their own foreheads, since the

Norman campaign was created for and is currently running only in

Colorado Springs. (It may be launched elsewhere in the future.)

Angry letters are going back and forth in the newspapers. Conservative

churches here are preaching against the campaign. City officials

are catching hell for accepting the campaign's banner dollars. I'm

not sure if the affair has made national news (has it?) but around

here we're starting to get a little tired of it all. Focus is now

launching a counter-campaign

starring a dog named Sherman that asks the question: When did

you last hear a dog moo? Alas, Norman is a metaphor, and not

an especially strong one. (I've never heard a dog moo, but basenjis

make a sound that is unlike any other noise I've heard out of any

other dog. Public Interest should done a little more research and

made Norman a basenji rather than a springer spaniel—but nobody

asked me.)

In conversations with people here, I get a sense that in a lot

of people's minds, Focus used to be on firmer ground. For a long

time they were mostly concerned with stabilizing shaky marriages

and opposing abortion, but the surprising influence of the gay marriage

issue in the 2004 elections caused them to shift a lot of their

energy to pushing a state consitutional amendment forbidding gay

marriage. (The amendment will be on the Colorado ballot this November.)

So what had been considered a city only moderately hostile to gays

is now considered a city extremely hostile to gay rights. Enter

Norman. And Sherman.

Alas, the discussion Norman and Sherman have fomented has been

broad but shallow. Nearly all research I have seen so far indicates

that human sexual identity is entirely genetic and unchangeable.

Focus claims that homosexuality is treatable and can be reversed.

Neither side seems willing to confront what I see ever more clearly

in the studies: That human sexual identity is a spectrum, and between

those who are clearly born gay and those who are clearly born straight

are people whose sexual identities drift across the boundaries for

reasons that are still completely obscure. Focus presents case studies

that look like they have persuaded male bisexuals to give up sexual

contacts with other males, but that's not the same thing as reversing

genuine homosexuality.

None of this bothers me directly. In a democracy, different sides

of an issue should make their cases before the public. What bothers

me is that the presence of an assertive conservative Christian organization

seems to be affecting job growth here, which I admit may be speculation,

but I see job creation happening all over the place, just not here—and

it makes me wonder. The town is beautiful, culture-rich, and inexpensive.

Gays and lesbians are not being lynched. The animus against gays runs

very deep...in a few people. Most citizens of Colorado Springs are

open-hearted and willing to let Norman—as well as Sherman and

everybody else—just be what they are and go on with their lives.

|

July

18, 2006: We're #1! July

18, 2006: We're #1!

We. Colorado Springs. Our frothy and mostly useless daily paper

announced that Money Magazine has named Colorado Springs

as #1 on their list of best cities over 50,000 population. I haven't

been able to lay hands on the magazine itself yet, but there's a

summary here.

The primary factors were things like easy commutes (the city is

physically small and the roads generally good) clean air and water,

moderate climate, good schools, lower-than-average housing prices,

and proximity to some spectacular recreation. Interestingly, although

the local business environment is quite good compared to a lot of

places, there isn't a lot of strong economic activity here right

now, especially in the high-tech industries, except things

relating directly to military aerospace. I have a couple of friends

with a fair bit of experience in networking and programming who

just can't find jobs, and that puzzles me. It's a gorgeous place,

the living is relatively cheap for a largish city, and it's close

enough to Denver so that anything you can't get here is an hour's

drive north.

So where the hell are the non-military jobs?

I'm a little short on time here today, but I'll address some theories

tomorrow, including some discussion of a really ugly fight

going on here that most of the country isn't aware of. Stay tuned.

|

July

17, 2006: Library Thing July

17, 2006: Library Thing

A few weeks ago I stumbled on LibraryThing,

a Web cataloging site for personal book collections. In recent months

I've been slowly scanning and entering books into a Win32 client

called Readerware (See my entry for April

13, 2006) as a disaster recovery mechanism, and LibraryThing

represents an alternative approach: Store your personal library

catalog online, and it won't burn up if your house does and your

laptop goes with it.

You can post up to 200 books with the free membership. I popped

for the $25 unlimited lifetime membership without half thinking.

I'm in the book business and it's a business expense; besides, I

need to know how this thing handles tonnage. You can find my

collection by looking for user Jeff_Duntemann.

Library Thing would be useful even if you could only see your own

collection. But it also allows you to see what other people own,

and for publishers, this can be very useful intelligence

about what the market is doing. For example, one of the most popular

authors among LibraryThing members is Neil Gaiman (American Gods,

Anansi Boys) which would not have been my guess. LibraryThing

uses the "cloud" UI mechanism, in which the point size

of items in a list is proportional to some value in the database;

in this case the number of copies of an author's books in member

libraries. (Click here

to see what I mean.) I spent a lot of time looking at the stats.

Among the books that I've entered so far, the most popular among

other LibraryThing members is Jered Diamond's Guns, Germs, and

Steel, with 1,318 copies in other member hands, and The Screwtape

Letters second, at 1,137 copies shared.

You can enter books by hand, either by entering an ISBN or Library

of Congress call number and submitting an online query, or by typing

in all the information. For older books without ISBNs, this is the

only way to go. If you already have your books cataloged somehow,

you can try their "bulk add" feature, which allows you

to hand LibraryThing a text file of some kind (typically an HTML

or CSV file exported from a local database) from which it will pick

ISBNs and perform automated lookups on up to three online library

databases. (I chose the default set, which is Amazon US, the Library

of Congress, and Amazon UK.)

The automated lookups are queued up so that they march through

Amazon and the LoC at a measured rate. If the system is popular

(as it was when I discovered it, due to a writeup in the Wall

Street Journal) it can take several days for your bulk adds

to get through the queue.

I added over a thousand books using bulk add, by submitting the

HTML export files produced by the Readerware library management

database I keep on my laptop. Of those thousand books, only 13 failed

lookup. Two were French translations of my Degunking books that

I later found on Amazon France. (Duh!) Two were remodeling books

originally published in Canada that I later found on Amazon Canada.

(Double Duh!) Seven were books that were in fact listed on the US

Amazon database, but for no clear reason Library Thing had failed

to find them. Two of the books remain unfound, even though I tried

looking for them in almost thirty online library catalogs around

the world. One was a Barnes & Noble reprint of Arthur Conan

Doyle's The Edge of the Unknown, and the other a mostly useless

book called How to Contract the Building of Your New Home.

It's still beta software, and there are some weirdnesses:

- By far its worst problem is that LibraryThing doesn't properly

list bylines on books with multiple authors. Degunking Windows

is listed in their database as by Joli Ballew only, and when I

tried to fix the author field by adding my name, the field automagically

rearranged itself to "by Jeff Ballew and Joli Duntemann."

As far along as the whole thing is, I'm amazed they haven't fixed

that one yet.

- The LibraryThing system still hangs up on me now and then, or

returns peculiar error messages, especially when I try to add

a book from search results returned by the Library of Congress.

Beta problems, I can only assume.

- LibraryThing doesn't seem to store book info in any sort of

cache, even for immensely popular books like the Harry Potter

series. Every single book instance entered into the system has

to be run past Amazon/LoC, etc. all over again. At least for books

carrying an ISBN, caching book data locally shouldn't be that

hard to do, and would make adding books to the system hugely

faster.

- LibraryThing has no way to disambiguate duplicate author names

in their own member-author program. In other words, I signed up

as a Library Thing author, with a special icon and treatment in

my profile. If there were another Jeff Duntemann who wanted to

register as an author, our books would have to be listed together,

with a manual notice that we were actually two different people.

Supposedly they'll fix this; it is, after all, still beta software.

- Some books—at least five—with a valid LoC call number

don't come up in searches of the LoC. My pre-ISBN 1966 Dell edition

of Intelligent Life in the Universe by Shklovskii and Sagan—hardly

a book of vanishing obscurity—failed every search I could

think of in every database. (Maybe the aliens kidnapped it...)

Note that this is not LibraryThing's problem; even the

Library of Congress's own site did not find 69-10184. Could there

have been that many clerical errors in logging LoC callouts?

- College textbooks seem not be in the online databases. I found

my dad's 1941 drafting textbook, but did not find either my own

1970 college drafting or Carol's 1969 high school physics textbooks.

Again, not LibraryThing's problem, but a weirdness nonetheless.

Some of my friends have asked me if it's a good idea to post the

contents of my library where everybody can see it. I thought that

one over carefully, and here is my response:

- I don't have any rare books worth breaking into the house to

steal. The most I've ever paid for a single book is $200, and

I have already destroyed it by scanning the fragile volume in

order to republish it. The binding disintegrated, and the loose

pages are now in a Baggie. Not worth much anymore, I'd guess.

I didn't even list it.

- Will the nasty old gummint decide I'm a dangerous radical by

analyzing my library? I doubt it. I have nothing by Marx, I don't

read porn, and own none of those old Loompanics classics about

picking locks and growing marijuana. I have maybe a dozen books

on politics, none of them especially strident. From ten steps

back, my collection suggests "harmless basement tinkerer

who reads SF and goes to church."

I haven't scanned all my books into Readerware yet, so what you'll

see up on Library Thing right now is perhaps half of what I own. Fiction,

humor, animals, electronics, health & medicine, travel, sociology,

literature, drama, and art have yet to go in, and there are quite

a few books still sitting in a box without having a shelf home yet.

So the experiment will go on.

|

July

16, 2006: From the Web Stats Search Query File July

16, 2006: From the Web Stats Search Query File

sasha brabuster

Of the Boston Brabusters, I'm sure.

are stingrays the under water animal used for clothing?

Ouch!

famous goodland kansas murders

Whoops. Better move to Lawrence instead.

list of sugar defusing plant manufacturers

Be prepared; exploding jelly doughnuts are rampant.

understanding dead people

They can be just so difficult at times.

fix stale gumdrops

Waste not, want not.

turkey vacuum tube solar system

There's an SF story in there somewhere.

nud photos

Sorry. In Colorado, nuds are nocturnal, endangered, and hide

well.

darwin fish wifi emblem

I want one of those!

home depot forklift break something

Lawsuit alert!

psychopathic mouse cursors

They curse cats violently and without remorse.

some women are ingested having sex with all animals with photos

If you spot a lion with photos, run!

|

July

14, 2006: Big Record Companies? Disposable. July

14, 2006: Big Record Companies? Disposable.

This morning's Wall Street Journal had a short article (not

available online) about major bands refusing to re-up with their

labels once their current contracts expire. Artists including Prince,

Jackson Browne, Pearl Jam and Ice Cube have basically told their

erstwhile labels that they are still willing to deal with them—but

this time on the artists' terms. This means turning down huge advances

but keeping copyright and a bigger chunk of the overall take.

The article is weak for a WSJ piece, because it doesn't

say much about how this state of affairs has come about. It's certainly

true that radio station playlists aren't the only ways to build

hits these days, as the article notes briefly and then changes the

subject. The Internet builds word of mouth in ways of which the

writer may not be aware, or may not want to admit, like P2P piracy.

It's not just Web sites anymore.

That yee-haw doofus Garth Brooks (who soiled himself in my esteem

by demanding the outlawing of used CD sales) dumped EMI, recorded

some new material at his own expense, and then cut an exclusive

deal with Wal-Mart to sell it to his core constituency. A doofus,

perhaps, but one who apparently knows who buys his CDs, and where.

Beneath all of this change lies something that the WSJ didn't

mention at all: It is getting ever cheaper and easier to create

digital music, and physical CDs are no longer the only way to deliver

it. (Stamping physical CDs can be done more cheaply and in smaller

quantities than ever before, too.) The technical expertise required

to record, mix, and cut an album has grown more common as the price

of the equipment has fallen. My sister and brother in law have an

entire recording studio in their basement and make decent money

publishing specialty music under their Dodeka

Records label.

All of this prompts one to ask: What value do gigantic record companies

add to the music industry? They used to provide the immense capital

investment it took to create, publish and promote new music, but

as the required capital has fallen, their importance has steadily

shrunk. They're not irrelevant yet (as some are already saying)

and won't be until the majority of all music sales are downloads

or direct CD sales. The only thing keeping them relevant is their

lock on the conventional B&M retail channel, and while that

will go on, the size of its piece of the overall music sales pie

will continue to fall.

Ok. Now go back through this entry and swap out "books"

for "music." Book publishing seems to be on much the same

path as music, if not so far along here in mid-2006. Linotypes,

IBM Composers, boards,

waxers,

and physical halftone screens are history, and have been since the

early 1990s. The capital investment required to create a print-ready

book image is now $2000 on the outside, and the skills required

for the job are a straight-line extension of word processing. If

you know Word, you're halfway to InDesign, PageMaker, or any other

layout app. Printing costs have plunged due to better presses, higher

productivity, and competition from overseas printers, particularly

in China.

Over time, authors who tire of watching horror scenarios like The

Incredible Shrinking Royalty Rate will choose the new path,

releasing books as ebooks and keeping older titles in print through

deals with smaller, POD-based publishers. It's already happening,

and the similarities to the music business are striking. I've asked

before and will continue to ask: What are big publishers actually

for?

Remembering, perhaps?

|

July

13, 2006: Gorgeous, but Tasteless July

13, 2006: Gorgeous, but Tasteless

I ran up to Denver this morning, to spend a little time drooling

in the aisles at the main Rockler

woodworking store and have lunch with Larry Nelson. Larry owns a

firm called Software Planning, and sells VinBalance, a package for

managing wineries and the winemaking process. He's also been heavily

involved in the interface between Walla Walla, Washington and the

surrounding agricultural community, and spearheaded the growth of

the regional farm market in Walla Walla.

A lot of fruit is grown near Walla Walla, and Larry and I talked

about a peculiar phenomenon that I have noticed over the past 25

years or so: Supermarket fruit has been looking better and better,

while simultaneously growing almost tasteless. The best example

is strawberries: They're huge, and red, and gorgeous, and so utterly

lacking in flavor that Carol and I have basically stopped buying

them. Table grapes are also on that path. Recent grapes have been

impressively large, but very watery and lacking in flavor. (They

remind me sometimes of the squishy green paintballs that I find

in the gully behind our house after the local teenagers have been

gaming down there.)

Apples that used to truly be delicious now simply look delicious.

We don't buy the delicious variety of apples anymore because they're

mealy and tasteless. The Braeburn apples we now eat are just ok,

and we wonder how long that will continue to be the case.

What's going on here? Larry and I have a theory: Factory farming

and mass grocery retailing select products based almost solely on

how they look. One imagines that corporate megafarms don't taste

their own products. Why should they? The only people who ever get

within a hundred feet of the actual fruit are hirelings without

any authority to steer the farming process.

There's almost no feedback loop between the consumer and the grower.

The consumer's only way to register dissatisfaction is to stop buying

the fruit, which (as with all such feedback-by-refusal) doesn't

transmit much useful information to the growers. And because huge

grocery chains are almost the only access that most people have

to fruit, the end result is that people just eat less fruit.

In Walla Walla and a lot of other cities in farm country, they

address the problem by bringing farmers directly to consumers in

farm markets. Here's a

nice article on the farm market in Reno, Nevada, which made

my mouth water. Strawberries that taste like...strawberries! What

a concept! Can I have some?

We're getting into fruit harvesting season here in Colorado, and I'm

ashamed to admit that there's a farm market here in the Springs that

I've never been to. Well, that's going to change. I've been

delighted by some of the surprises I've found in locally vinted wines

made with grapes grown here in Colorado. What works for the wine may

work for the fruit as well. I'll let you know what I find.

|

July

12, 2006: Odd Lots July

12, 2006: Odd Lots

- Conspiracy buffs may be interested in the contention that Hilary

Clinton is a closet Republican. Horrors! Hey, are we that

short of conspiracies, guys?

- People have been sending me links to bobblehead pages. Evidently,

bobblers are very big in American culture. Here's

the best collection I've seen. Want John Gotti or Jesus nodding

on your desk? You got 'em. Sigmund Freud? No problemo. Edgar Allen

Poe? Condi Rice? They're all here.

- Actually, I can't quite decide which I want for Christmas: The

Condi Rice bobblehead or the Pope

Innocent III action figure.

- I learned the other day that big band leader Fred Waring (of

Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians) popularized

the blender appliance that later bore his name. The actual

blender concept was invented in 1922 by a guy named Stephen Poplawski,

but he didn't have a band.

- Bigelow Aerospace has finally launched its one-third

scale model of an inflatable space station on a converted

Russian ICBM. Inflatables are an obvious way to create habitable

space in space, and it's always puzzled me a little why NASA hasn't

pursued it. (And don't say that that's because "it's a good

idea" even if it's true.)

- Steampunkers may enjoy Crabfu's

Steamworks, a collection of some pretty clever steam-driven

models, including a model of a steam-driven rowboat—driven

by oars. (Thanks to George Ott for the pointer.)

- Useless knowledge: Betty Boop was originally created as a floppy-eared

anthropomorphic French poodle by the Fleischer animation gang,

back in the early 1930s when nearly all cartoon characters were

funny animals. She appeared in several cartoons as the girlfriend

of Fleischer's popular Bimbo character, who was also an anthropomorphic

dog. Betty grew so popular after a few cartoons that Fleischer

redesigned her as fully human, then was forced to drop Bimbo because

a dog with a human girlfriend suggested bestiality. By the way,

you can legally download perhaps the

weirdest and most totally surreal cartoon ever made in b/w.

This Snow White has nothing in common with Disney!

|

July

11, 2006: The Uncanny Valley July

11, 2006: The Uncanny Valley

Back in 2001, I saw previews of a movie called Final Fantasy:

The Spirits Within, and my initial strong reaction was, Yukkh!

That's creepy! The film attempted photorealistic human characters,

and did about as well with the animation as one could do circa 2000,

but many people commented that the CGI humans were a serious turn-off.

Since then I've read of animators tweaking CGI human faces to make

them just a little less human-looking (this was done in the

Shrek movies and in The Incredibles) because when

animated humans are too close to real (without quite being fully

convincing) they inspire in people either revulsion or a kind of

nameless dread. I've known of the effect for years, but today was

the first time I knew it had a name: The uncanny valley.

Explaining the term itself may require a graph. I borrowed the

one below from Wikipedia, and if you're interested in the concept

I encourage you to read their

very detailed article on the concept.

If you start with something as unlike a human being

as a robot welder, people are basically indifferent to it. (They

may correctly choose to stay out of its way, but that's a different

issue.) As you move toward things that begin to resemble the human

form, emotions engage and people respond more positively, especially

if pains are taken to avoid well-known negative images. (The Devil,

Hitler, etc.) Even odd anthropomorphic figures (think Goofy or Reddy

Kilowatt) are generally well-received if they smile and don't do

obnoxious things. At some point, when your representation of a human

being gets close enough to photoreality, acceptance goes off a cliff,

and the figure becomes creepy and disturbing. At some point further

on, if the representation becomes indistinguishable from a healthy

human face, acceptance rises again.

The Wikipedia article doesn't speculate as to why

all this should be so. The only reason I can think of for the uncanny

valley is an adaptive subconscious tendency to avoid diseased people

or corpses. We are very good at recognizing real faces, and there

comes a point along the continuum between a cartoon and a photo

where the cartoon becomes so lifelike that this ancient machinery

kicks in, and instead of a cartoon we see a face without the many

subtle indications of healthy life. The dragons of the subconscious

suggest zombies or mythic supernatural creatures instead, and we

get low-level willies.

This is significant to me because I'm tinkering with

a new novel that involves AIs being evolved within an artificial

world called the Tooniverse. The AIs are initially animated as obvious,

simple cartoons (think Cartoon Channel things like "Fairly

Odd Parents" and further on, "King of the Hill")

and as they evolve more closely to human levels of intelligence,

they are given more lifelike animated human figures. The primary

AI (named Simple Simon) understands the risk of coming to appear

a little too human. "I don't want to actually be human,"

Simon says to one of his fellow AIs. "I just want them to take

me seriously." This is hard when you resemble Homer Simpson,

but Simon doesn't want to creep people out, either.

By the way, is it just me, or should bunraku

puppets (which always seemed like high-resolution Muppets to me)

be on the opposite slope of the uncanny valley?

|

July

9, 2006: A Different Kind of Vision July

9, 2006: A Different Kind of Vision

Kevin Anetsberger was kind enough to send me a sketch of what he

saw in the rock beside the La Garita Arch:

|

July

8, 2006: A Lulu of a Problem July

8, 2006: A Lulu of a Problem

Boy, this is a weird one. I tried to set up an account on lulu.com,

Red Hat founder Bob Young's print-on-demand and ebook publishing

startup, which has a lot in common with my idea of an ebook gumball

machine. I can access the lulu.com Web site without any trouble

or delay. But any time I attempt a transaction that involves Lulu's

servers, the browser just grinds and grinds until it times out.

This happens with both Firefox and IE, so it isn't a browser configuration

issue; both browsers allow session cookies and Javascript. I establish

https connections with many other ecommerce sites all the time,

from monsters like Amazon to small furniture retailers. I've never

seen anything like this.

It made me nuts, and I spent an afternoon poking at the problem.

I spent an hour in a chat window with one of Lulu's support people,

and we parted company with neither of us the wiser. Then, on a hunch,

I went downstairs and logged into Lulu from one of my lab machines.

Bang! No problemo, even on my doddering old 1998 Dell Dimension.

Further checking proved that I can use Lulu normally from every

other machine in the house—except the best one, the one I use

for almost everything. Arrgh!

So the problem really is with my primary machine up here. Windows

2000 SP4, 3 GHz Pentium 4, 4 GB RAM, half a terabyte of disk. Unloading

Zone Alarm didn't change anything. Unloading Skype didn't change

anything, and there's nothing else running that fools with networking

at all.

I had hoped (and still hope) to publish my re-issue of The New

Reformation through them, but until I can figure out why my main

machine won't talk to their database servers, it's no deal. Let's

just say that I'm open to suggestions.

|

July

7, 2006: Our Lady of the Rock Arch July

7, 2006: Our Lady of the Rock Arch

Pete Albrecht, who is nominally a Lutheran, has stolen a very Catholic

march on me by spotting the image of the Blessed Mother on the perforated

rock ridge we clambered around on this past weekend:

Or perhaps it was just the image of St. Pareidolia,

patron of artistic cracks in rocks and scorch marks on tortillas.

I'm ashamed to say that I was staring right at it and never saw

it. Damn.

By the way, if you want to go there and see for yourself, Bp. Sam'l

Bassett looked up the coordinates and directions and sent them to

me:

N 37 48.833' W 106

22.639' at about 8900 feet

To get there, take

US Hwy 285 to the La Garita/County Road G exit. Go West (and a

tad north) about 5.75 mi to La Garita. CRG becomes CR38A about

3/4 mile West of La Garita. Continue West about 1.5 mi to junction

of CR38A and CR41G. Go Left (South) on CR38A about 4.3 miles.